Classics In September — Our classics series has featured such household names as Arthur Conan Doyle, James M Cain and Jim Thompson, all of whom have sold millions of books, inspired film and TV adaptations and can truly be said to have stood the test of time. Today we look at someone who was so obscure that he was published under a pseudonym to avoid being confused with a popular author of medical crime potboilers. Robin William Arthur Cook was a dissolute old Etonian who lived in London’s demi-monde in the 1980s and early 1990s, and wrote under the name of Derek Raymond. He died, little noticed by the public, in 1994. So why does he deserve to be mentioned in the same breath as other acclaimed authors in our series?

Classics In September — Our classics series has featured such household names as Arthur Conan Doyle, James M Cain and Jim Thompson, all of whom have sold millions of books, inspired film and TV adaptations and can truly be said to have stood the test of time. Today we look at someone who was so obscure that he was published under a pseudonym to avoid being confused with a popular author of medical crime potboilers. Robin William Arthur Cook was a dissolute old Etonian who lived in London’s demi-monde in the 1980s and early 1990s, and wrote under the name of Derek Raymond. He died, little noticed by the public, in 1994. So why does he deserve to be mentioned in the same breath as other acclaimed authors in our series?

Raymond cast a broad and influential literary shadow. He is widely regarded as the ‘godfather’ of the English noir novel, and was a writer prepared to visit dark places shunned by his contemporaries, thus preparing the ground for the kind of frank and graphic accounts of human violence and despair made popular by more recent authors such as Val McDermid. A writer in The Times said that he wrote “with a feverish metaphysical intensity that recalls Donne and The Jacobeans”, and in that same newspaper, in 2008, he was listed in their feature The Fifty Greatest Crimewriters.

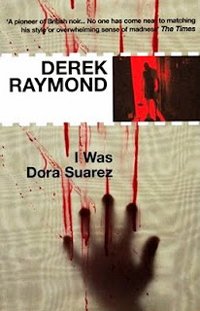

Raymond wrote in a style which has been poorly imitated since, but at the time was totally unique and beyond the comprehension of most fellow writers, publishers and all but a devoted body of readers. He will be best remembered for his five Factory novels. He Died With His Eyes Open (1984), The Devil’s Home On Leave (1985), How The Dead Live (1986), I Was Dora Suarez (1990) and Dead Man Upright (1993). The Factory is the grimy headquarters of a fictitious branch of the Metropolitan Police called A14, based in Poland Street, Soho. A14 is tasked with investigating unexplained deaths; the building and its officers are feared by criminals and despised by the mainstream police.

Raymond wrote breathtaking prose and took risks that would have given conventional crime writers seizures. The main character, who narrates the greater part of the books, is a Detective Sergeant. His wife has been committed to an institution for the criminally insane having caused the death of their child. He is as hard as nails, though not invulnerable; he is street-smart, and has a mouth on him that easily silences both his enemies and his colleagues; he lives in an anonymous, autistically neat flat somewhere in the suburbs, and drives a Ford Escort. Apart from his preferred drink being pints of Kronenbourg he remains a shadowy physical presence. Raymond’s masterstroke is to keep this avenging angel nameless. He has no name, so he is none of us – but then again he is everyone of us.

The nameless Sergeant has a revulsion for the living is as bitter as absinthe, but he cares for the dead like a man on a mission to absolve humanity from the great weight of all the evil deeds ever committed in its name. He walks the litter-strewn and rain-swept streets of suburban London, armed only with his own morality and a visceral contempt for those who commit the ultimate sin of extinguishing life – no matter how damaged or wretched the victim.

The first chapter of I Was Dora Suarez is the most terrible, terrifying and gut-churning 20 pages ever written in English fiction, and yet it still resonates with a kind of decadent poetry, like the verses Dante Gabriel Rossetti entangled with the golden hair of his dead wife as she was buried – and then retrieved months later because he was short of money. Staining romance and compassion with corruption, Raymond takes us beyond the periphery of hell and onto its inner nightmarish streets, usually alone and unarmed.

The first chapter of I Was Dora Suarez is the most terrible, terrifying and gut-churning 20 pages ever written in English fiction, and yet it still resonates with a kind of decadent poetry, like the verses Dante Gabriel Rossetti entangled with the golden hair of his dead wife as she was buried – and then retrieved months later because he was short of money. Staining romance and compassion with corruption, Raymond takes us beyond the periphery of hell and onto its inner nightmarish streets, usually alone and unarmed.

There could never be a realistic screen adaptation of a Factory novel. The sheer depth of depravity and startling violence which Raymond describes would never get past a censor. There is little or no redemption in his books. Raymond is, truly, the poet of death. Yes, the villains are usually brought to some kind of rough justice, but the dead remain dead and the innocent stay violated. The cruelty inflicted on them remains seared on our consciousness, and if our dour avenger physically survives, we suspect that it is only a matter of time before he is destroyed either by some criminal with a blacker heart than his, or by one of his negligent and time-serving superior officers.

Raymond returned to London towards the end of his life, drinking in The French Pub and keeping company with the literary avant-guard, including Iain Sinclair, as well as ageing former acolytes of the Kray brothers. Ironically, at the time when his work was beginning to emerge from cult fiction into the mainstream, he succumbed to cancer. He died in July 1994, and was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery. The five Factory novels are all available in paperback, and two are available as Kindle editions.

An excellent pen picture of Derek Raymond. One of the greats, certainly of that strain in British crime fiction that trades in an uncompromising baroque nastiness.

No mention of The Crust on its Uppers? I can’t believe it gets no love these days — sheer music.