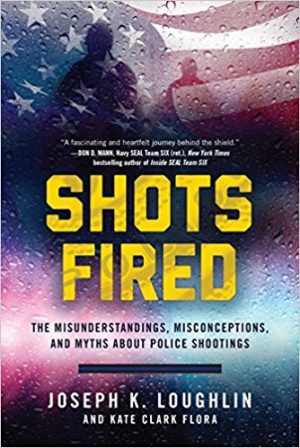

In Shots Fired, true crime author Kate Clark Flora has teamed up with Joseph K Laughlin, former assistant chief of police in Portland, Maine, to produce what is a remarkable non-fiction work that will be of interest to crime authors and readers too. For all its limitations, it’s a must-read for people concerned about gun crime and police violence.

The book is based on interviews with dozens of police officers involved in deadly shootings. They recount how and why they reacted as they did during the event and the impact on them afterward. Written in part as a corrective to the perceived anti-police bias among some members of the public, the news media, and people with a full range of political agendas, it effectively underscores a number of key points and aims to dispel common myths.

Citizens often wonder why police don’t just shoot weapons out of suspects’ hands. Or shoot to wound them. Television and movies would suggest that police have plenty of time to make such calculations, take careful aim at their suspect, and are accomplished marksmen. In real life, the compressed timeframe in which police actions typically occur does not allow for a carefully aimed shot. The situation may be confusing, people are moving, and armed suspects may be charging the officers or putting others at risk.

The public also wonders why so many shots are fired. They may not realize that suspects high on drugs or adrenaline or both aren’t stopped by a single bullet – even if that bullet would eventually prove fatal – they keep coming. The officers’ goal is to eliminate the hazard, to themselves, to other police, to the public. A single bullet doesn’t achieve this.

No fictional account could be more powerful than the book’s second-by-second reconstruction of the confrontation with the Boston Marathon bombers by Watertown, Massachussetts, police officers. Tamerlan Tsarnaev was hit nine times by bullets from a .40 caliber Glock and still ran toward the police, firing. When his gun was empty, he threw it at an officer and kept coming. The police thought he might have a bomb strapped to him. Nevertheless, they tackled him, and he went down. He was still fighting them when his younger brother ran over him with an SUV, making his escape. Tsarnaev was dragged 20 feet down the street and still struggled with the officers.

In the book’s efforts to overcome misconceptions about the use of deadly force promulgated by entertainment media and the news and information media, it has an unabashed pro-police bias. The interviews with the police officers are truly moving. Killing another person is not something good officers take lightly. Often they are off patrol work for many months afterward. Some can never return to duty.

The book might have been stronger if some of the interviews were with police whose actions were more ambiguous (impossible because of legal liability), or if there were greater acknowledgment that sometimes there are bad officers. In the closing chapter’s list of 10 ways the public can support the police, one might have been improving methods for weeding such individuals out of a department. But that was not the purpose of this book.

Reading this book, you’re likely to develop a greater appreciation for the split-second decision-making skills police are routinely called upon to deploy and the inevitability of errors. You also will have greater appreciation of the investigatory process – the news media blasts officers’ actions within hours of a shooting event, whereas a full investigation takes time. You will know more about the toll on police officers. While the terrible occurrences in Ferguson, Missouri, Baltimore, Staten Island, and elsewhere are high in the public consciousness, how many Americans are aware that in the decade from 2003 to 2012 there were more than 575,000 felonious assaults against police officers, almost 200,000 of which involved a weapon?

Readers will come away with an appreciation of the need for greater police training and education too. Training not just to deal with police issues, but the fallout from drug abuse and alcoholism, poverty and unemployment, homelessness, the underfunding of the mental health system – all of which produce social problems that wind up in the laps of public safety personnel on a daily basis.

Terrence M Cunningham, deputy executive director if the International Association of Chiefs of Police says in his a foreword, “It is only through respectful, thoughtful conversations that we will find the solutions necessary to move forward. And it is through these continued difficult discussions that communities can begin to heal.” While this book tells one side of the story, it’s a side too rarely discussed in inflammatory news stories and a rush to judgment. It’s an exciting read, and one that will give every person who reads crime stories – and the daily newspaper – a new perspective on unfolding events.

Skyhorse Publishing

Print/Kindle

£14.94

CFL Rating: 4 Stars