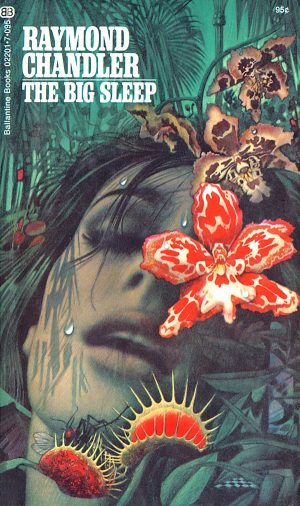

It’s impossible to imagine a proper historical survey of noir fiction without reference to Philip Marlowe, the iconic character created by Raymond Chandler in his ground-breaking 1939 debut novel The Big Sleep. Marlowe is the prototypical hardboiled private eye. Street-smart and tough, he reads people and situations at a glance and acts with cold composure and suave calculation. The hard-drinking, cigarette-smoking loner is a product of the deadpan detective characters and colloquial street slang style born in the pages of the 1920s pulp magazine Black Mask, where Chandler wrote alongside Dashiell Hammett and James Cain. After the big success of The Big Sleep, the Marlowe adventures continued for six more books, including Farewell, My Lovely.

Although forged from Black Mask’s tough-guy mold, Chandler’s Marlowe is a far cry from Hammett’s iconic blonde satan Sam Spade, who wades indifferently through the mean streets of crime and carnage. Marlowe is tempered by distinct morals. In the steamy, corrupt heart of 1930s Los Angeles, he is a shining knight striving to do the right thing. He is synonymous with the dark sensibility that thrived in Black Mask and was canonised forever in the popular imagination by Humphrey Bogart on film, but Marlowe is a bit more evolved. The contemplative dick plays chess, listens to classical music, and is comfortable with this feminine side. A fastidious dresser, Marlowe’s discerning eye extends to fashion, architecture and interior design. He is the very model of the metrosexual detective – ahead of his time – in the burgeoning urban sprawl of LA.

As The Big Sleep opens, Marlowe describes his new client’s mansion in covetous detail. Guy de Brisay Sternwood is a decrepit general whose two wicked daughters have too much time on their hands and find trouble easily. The youngest and most trouble is Carmen Sternwood, who insinuates herself into the criminal underworld and is soon blackmailed. Older and smarter Vivian is also a piece of work. Her husband Rusty Regan ran off despite his cushy life. The general was fond of the tough Irishman, who helped keep the Sternwood girls in check. Although Marlowe is hired to fix the Carmen problem, the mystery of Rusty’s disappearance is ever looming in the background.

Following up on a lead, Marlowe enters the residence of smutty book dealer Arthur Geiger and finds his dead body, a drugged, naked Carmen Sternwood and the remains of a naughty photo shoot, minus the pictures. Marlowe soon meets a lot more colourful crooks and dames, including Eddie Mars, Joe Brody, and Agnes Lowzier, as he attempts to recover the incriminating photographs and finish the job. Three bodies later, Marlowe has had several run-ins with both Sternwood girls, and although sick to death of them, he is far from done.

Chandler’s gift is creating living characters using descriptive prose that immerses you into the hazy drama of Los Angeles and its underworld denizens, sleazy hotels and bars, all rendered as vividly as a Technicolor movie. Colloquial language and trenchant similes describe people, guns and streets in a manner both amusing and profound. Chandler’s prose settles so deeply into your consciousness that you feel you’re there with Marlowe as he spars with criminals and molls, hiding behind tropical bushes, or careening down the LA’s rainy boulevards. The street-smart private eye is not always in control, however, in a scene where his car breaks down and he falls into the hands of dangerous criminal Canino, as “Fate stage-managed the whole thing.”

Chander’s art of storytelling follows certain principles laid out in a 1944 article for the magazine The Atlantic Monthly, which later was re-worked as a 1950 essay of the same title, The Simple Art of Murder. In this now standard reference work, Chandler opines on the historical development of detective fiction, the influence of Dashiell Hammett, and the emphasis of character over plot. Soon after, this title was given to a collection of Philip Marlowe adventures, which were really re-worked earlier stories featuring the detectives Carmady and John Dalmas, the original incarnations which Chandler later cannibalised to form the character Philip Marlowe.

Chander’s art of storytelling follows certain principles laid out in a 1944 article for the magazine The Atlantic Monthly, which later was re-worked as a 1950 essay of the same title, The Simple Art of Murder. In this now standard reference work, Chandler opines on the historical development of detective fiction, the influence of Dashiell Hammett, and the emphasis of character over plot. Soon after, this title was given to a collection of Philip Marlowe adventures, which were really re-worked earlier stories featuring the detectives Carmady and John Dalmas, the original incarnations which Chandler later cannibalised to form the character Philip Marlowe.

Marlowe’s metafictional detective agency

The Big Sleep is an important historical innovation in detective fiction, where noir breaks away from the genre’s low-brow status, pushing its boundaries into the larger world of literature. Chandler’s literary playfulness and emphasis on character over plot is evident in his advice to writers who get mired in plot: “When in doubt have a man come through a door with a gun in his hand.”

Director Howard Hawks, while consulting with Humphrey Bogart during the filming of The Big Sleep, famously wired Chandler to ask him who actually killed one of its characters, to which Chandler responded that he didn’t know either.

For a writer ostensibly unconcerned with plot, the main plot of The Big Sleep’s hinges, at its halfway point, precisely on the act of storytelling. Marlowe has finished his assignment, but he’s still got a lot of explaining to do to the police. The official story needs to be told, truthful or not. In a marvelous meta-fictional moment, Marlowe, the district attorney and the police chief, like literary editors, gather and transform the first half of the book into a cover story for the press and thus protect the reputation of General Sternwood, a mutual friend of both the DA and Marlowe.

But Marlowe’s not the only one concocting stories. There’s an orgy of plotting by the characters in Big Sleep. Everyone’s got a front, a story designed to deceive or delay the truth. From Eddie Mars, the smooth-talking racketeer who smells opportunity, to Joe Brody, the impulsive blackmailer, to Eddie’s wife Mona, and especially the Sternwood sisters, who have the most to hide.

Marlowe feels compelled to act, as opposed to the knight depicted on a tapestry at the General’s mansion, who never quite reaches his damsel. On his own initiative Marlowe spends most of the General’s fat paycheck searching for the missing Rusty Regan. In the book’s dark second half, Marlowe himself becomes the story when he discovers the truth and must decide how to tell it to the old man: “Me, I was part of the nastiness now.”

A hardboiled legacy

Raymond Chandler, the poet laureate of noir, has been so influential it almost goes without saying that crime fiction and popular film culture owes its hardboiled image of the private eye to him. Chandler’s influence is seen in a whole generation of 20th century writers including Ross MacDonald, Walter Mosley, Robert B Parker (who himself finished Chandler’s last, uncompleted Marlowe book Poodle Springs), James Ellroy and Elmore Leonard, to name a few, an influence that continues well into the 21st century. Without Marlowe, it’s hard to imagine an Easy Rawlins or a Bosch.

Notable also as a screenwriter, Chandler penned the classics Double Indemnity, Blue Daliah and Strangers on a Train. But his greatest contribution may be the widespread use of first-person narration in film noir. Try imagining your favorite noir without the detective’s cynical, laconic voiceover. But if you really want to feel the Marlowe effect, open a random page of The Big Sleep and you’ll be drawn immediately to the dark and romantic milieu of 1930s LA with the urban knight Philip Marlowe as your world-weary, wise-cracking guide.

Read our introduction to Raymond Chandler. Can’t settle on a noir flick for the weekend? Cue up Chandler on Film: Six to Watch.