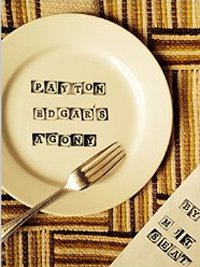

London, 1962. Payton Edgar is the restaurant critic of the London Evening Clarion. He is also an insufferable snob. Add to that his vanity, sharp tongue and vague air of misanthropy, and you have one of the least appealing amateur detectives of recent times. When his editor demands that he provide copy to cover for the paper’s agony aunt who is absent due to what is squeamishly referred to as ‘a ladies’ operation’, he is initially outraged, but then reluctantly agrees. Dispensing with the Peggy’s Problem Postbag byline, he invents an equally fictitious persona – that of Dr Margaret Blythe – and proceeds to answer the genuine letters as caustically and as offensively as possible.

One of his letters is a plea for advice from a woman who has a stable marriage, but has fallen for a dashing but controlling fellow thespian at the local amateur dramatic society. After dishing out some abrasive advice, Edgar is dismayed to find that the woman has apparently committed suicide. His curiosity gets the better of him, and he poses as a member of the am-dram society to meet the dead woman’s husband and sister. When he hears that the case is being treated as a murder, he has a tiny tingle of conscience, and decides to investigate further.

Edgar cannot help himself. While telling more and more lies about his alter ego, Dr Blythe, he attends the funeral of Helen Capstick, the unfortunate woman whose fall from a high rooftop has disrupted rehearsals for the Claremont Dramatic Society’s eagerly awaited performance of The Merry Widow. Fraudulently establishing himself as a member of the cast, he worms his way into the mourning Capstick household – husband John, son Frank, and sister Jenny. The funeral raises more questions than it answers, and with the chief murder suspect – Helen’s thespian lover – discovered hiding in his old mum’s loft, the bluff policeman investigating the case thinks he has his man and welcomes Edgar’s persistent questions like a case of anthrax.

Edgar is unwilling host to his bedridden, aged aunt, and is startled to learn that her latest carer is none other than the daughter of a fabulously wealthy family of fashion designers. With her help, he blags his way into a gala couture show and, in embarrassing circumstances, learns that the dynamics of the Capstick family are not what they appear to be. There is a dramatic and bloody finale to the tale involving a brass-headed walking stick and one of Fleet Street’s antique printing presses.

The book is delightful, in the most literal sense of the word. Hardly a page goes by without one of Payton Edgar’s pompous judgments or acerbic put-downs producing a smile. Edgar has something of Mr Pooter about him, but little of that man’s goodness. The author proves himself an excellent satirist. Is it great crime fiction? Probably not, but I was too busy chuckling at Payton Edgar to mind too much. The book came as a welcome soufflé – light but sharp – in contrast to the more heavyweight fare of serial killers, child abductors and psychopathy that currently seem to be standard in crime fiction. Don’t expect a cosy read, though. Payton Edgar, were he real, would have the politically correct posting an online petition faster than you could say, “I’m offended.” There are one or two unfortunate typos along the way, mostly homophones like root for route, but these don’t come close to spoiling what is a cruelly funny and entertaining read.

Proceeds from this book are going to the Sussex Cancer Fund.

Self-published

Kindle

£1.60

CFL Rating: 4 Stars