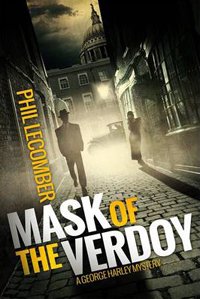

“The dramatic finale is magnificently melodramatic, and ends the book – an excellent debut – in fine style.” That was our verdict when we recently reviewed Mask of the Verdoy by new crime author Phil Lecomber. Now based in the West Country city of Bath, he grew up in London and worked for 25 years in the art security business. We asked Phil to talk about his arrival on the crime fiction scene…

So, can you give us an introduction to your 1930s detective George Harley?

Harley is a veteran of WWI, where he served in a trench-raiding squad. But his experiences in the war and a subsequent ill-fated career in the Secret Intelligence Service have politicised our man to the point where he’s as eager for change as the extremists campaigning in the East End. He now has a serious chip on his shoulder, and welcomes any opportunity to rail against the entrenched British class system. He also has a boyish enthusiasm for all things modern and is a believer in the liberating power of knowledge. He is an avid fan of the new Jazz music and a collector of the latest technology – including Mabel, his Norton CS1 motorbike with sidecar, and a portable Leica 35mm camera.

One of the most defining experiences of Harley’s life was the brutal murder and decapitation of his fiancée Cynthia at the hands of the serial killer Osbert Morkens, an event that plunged him into a dark period of drink and drugs, haunted by daily nightmares of the trenches and the discovery of Cynthia’s headless corpse.

Mask of the Verdoy is a long and very intense first novel. What was its genesis? Have a few prototype novels ended up in the waste bin?

No, there aren’t any prototypes in the bin. I’d written a couple of unpublished novels, but still hadn’t found my voice. I’d fully plotted Mask of the Verdoy, and had just begun on the first draft when a chance meeting on a train led me to rethink the story as a possible TV serial streamed on the internet, rendered in motion-capture-assisted animation. I know – crazy! After a year of working on the project it became obvious that it wasn’t going to happen. I returned to the novel format to discover that my writing style had been coloured by the process of creating the screenplays for the episodes – an improvement in my opinion. That’s why the story is mainly driven by the dialogue.

What inspired your vision of 1930s London?

During the early 1980s I was employed as a steel fixer, installing safety equipment on some of the city’s tallest buildings and iconic landmarks. Seeing London from above made it easier to spot the juxtaposition of old and new: a muddle of blackened Victorian chimneys nestling in the hollows between office blocks; the towering edifices of the Square Mile following the meandering contours of a medieval street plan. I found this sense of the barely concealed past incredibly alluring. I remember working on the redevelopment of the old warehouses flanking the Thames, the way the timbered flooring still bore the perfume of the spices once stored there over the previous centuries. I’m sure it was this sense of a tangible connection to the past that steered me towards recreating London in the 1930s for the George Harley mysteries.

The novel is very London-centric. Do you worry that international readers might not get the atmosphere and references?

I understand there’s a gamble there – especially with the use of slang – but I’d like to think that once you’re past chapter two the plot will have caught you in its grasp, and there’ll be no turning back. Personally I love books that introduce me to an exotic world, for example Krajewski’s Eberhard Mock stories, or Akunkin’s Erast Fandorin books. And, isn’t every book set in a sufficiently distant past full of references that we may need help with? The important thing is that these references don’t get in the way of the story. I’d like to think the reader could plough through the novel without looking up one slang term in the glossary, or without Googling one historical reference.

Which writers have influenced you, and are there any authors who you read for sheer pleasure?

For the atmosphere of 1930s London I’ve drawn great inspiration from the likes of Patrick Hamilton, Norman Collins, Gerald Kersh, James Curtis and Robert Westerby. Of course, it’s easy for your reading to become overtaken by research but I’m still an avid reader for pleasure. Some particular favourite authors of mine are: Angela Carter, Graham Greene, Michael Chabon, Michel Tournier, Ray Bradbury, Alexander Baron… it’s difficult to know where to stop with such a list. In the crime fiction genre I don’t think you can beat Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley books. What a unique creation Tom Ripley is – a man almost completely devoid of morals, a liar, murderer, conman, and yet we’re rooting for him all the way.

Harley is old enough to have fought in the Great War, and young enough to be available to serve in WWII. What next? Is he going back or forward in time?

Oh, definitely forward. The second book in the series, The Grimaldi Vaults, takes us into 1933. There’s a Weimar cabaret star, child abduction, a dismembered body in a suitcase, occult rituals, Nazis and… scary clowns!

The death of George’s fiancée Cynthia is pretty dramatic. Will we get to know the full story?

We’ve only so far been teased a little with the serial killer Osbert Morkens, the psychopathic Professor of Ancient History responsible for Cynthia’s demise. But I wouldn’t be surprised if Harley’s arch-enemy makes an appearance in the second book. After all, escaping from a padded cell in Broadmoor should be a cinch for an evil genius, right?

Like Sherlock Holmes, Harley resorts to stimulants when his brain flags. What will happen when he has exhausted the contents of the little wooden box on his bookshelf?

Well, Harley can always rely on his old contact Limehouse Lil for his opium, or pen yen. Lil is Cynthia’s sister and, along with her Jujitsu-practising daughters, makes an appearance in the second book. As for the Dreambugs, who knows exactly where they were sourced from? The only way Harley could replenish his stash of these hallucinogenic crustaceans is if his Uncle Blake made a miraculous return. But seeing as the old Victorian adventurer was lost in a mudslide all those years ago in darkest Peru that’s not very likely to happen, is it?

Read our review of Mask of the Verdoy here.

Though one understands Lecomber’s desire for authenticity of his 1930s London one questions the necessity of including offensive terminology and descriptives that could be avoided such as: Jew-boy. Or Although, funnily enough, he does knock about with Yids. Yids, grasses and bolshies. He ain’t too particular by all accounts.

Language of the times, perhaps, but with a 2014 copyright one would think the times could be set without the need of brutal reminders.