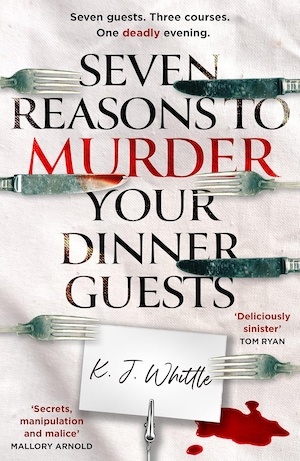

KJ Whittle’s debut novel, Seven Reasons to Murder Your Dinner Guests, is a psychological mystery that balances the intrigue of a traditional whodunnit with the moral uncertainty of a contemporary character study. The puzzle begins when seven strangers are invited to a dinner party at a subterranean London restaurant called Serendipity’s. None of them know the host, nor why they have been invited.

After a lavish meal and some decidedly uncomfortable conversation, each guest receives an envelope that contains a chilling prediction: the age at which they will die. What first appears to be an eccentric or tasteless joke soon proves to have deadly consequences when, just weeks after the party, a guest dies at precisely the age predicted.

As time passes and other predictions begin to come true, the surviving guests are forced to confront the possibility that they are unwittingly playing someone’s deadly game. The tension that drives the story stems from the question of whether the deaths are acts of fate, coincidence or calculated murder and from how each guest responds to their supposed destiny.

The premise is reminiscent of Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None, but the novel’s substance is distinctive. The pull lies not only in the mystery itself but also in the philosophical dilemma it poses: what would you do if you knew when you were going to die? Whittle uses that question to explore the characters’ deepest fears, flaws and desires, examining how knowledge of mortality corrodes or cleanses the soul.

The use of multiple perspectives allows each of the seven guests to narrate parts of the unfolding story. The shifting viewpoints add both variety and depth to the story, facilitating a kaleidoscopic understanding of events. Some guests respond to the prediction with denial, others with obsession or fatalism. For a few, it becomes a source of liberation, while for others, it triggers a slow psychological collapse.

Each perspective presents the same mystery through a different emotional lens, which gives the story texture and momentum. Vivienne, one of the most prominent narrators, is drawn with particular care – sharp, reflective and deeply flawed. Her arc, charting the erosion of her composure and her eventual reckoning with guilt, anchors the book and provides a solid grounding amid the chaos.

The pacing of the novel is deliberately variable. Whittle alternates between stretches of relative calm and sharp bursts of violence or revelation. Time moves unevenly – weeks and months pass between the deaths – meaning that the reader, like the surviving guests, lives with the growing dread of inevitability. This slow burn suits the story’s tone, allowing tension to accumulate gradually as the guests move inexorably towards their fates.

At times, however, the pacing can make sections of the novel feel elongated, particularly when Whittle lingers on internal monologues or detailed backstories. But even in these slower passages, there is an undercurrent of menace that sustains interest. The narrative mirrors the psychological experience of waiting for disaster: a blend of dread, denial and perverse curiosity.

In fact, what distinguishes Seven Reasons to Murder Your Dinner Guests from a conventional murder mystery is its exploration of morality and fate. The guests are, of course, not random strangers but (deeply unlikeable) individuals whose past actions and choices resonate with their current predicament. As the story progresses, it becomes clear that the dinner party was not as arbitrary as it first appeared.

Whittle uses this structure to ask unsettling questions about guilt and justice. Are we ever free from the consequences of our actions? Do we deserve the punishments life – or death – deals us? The novel’s title itself suggests a grim symmetry: the ‘seven reasons’ may refer not only to potential motives for murder but also to the moral failings that make each character vulnerable. In this sense, the novel is as much a moral allegory as it is a thriller.

Despite the weighty issues discussed, the dialogue feels natural and well-tuned to each guest’s voice, and the descriptions are vivid without slowing the pace. The atmosphere of the restaurant, the sense of enclosure and unease, and the subsequent psychological isolation of each character are evocatively portrayed. Moments of humour and social observation punctuate the dread, offering brief relief while deepening the novel’s realism.

As the years pass, the death toll rises and the surviving guests grow more paranoid, the novel becomes a study of psychological disintegration. The fear of death exposes the worst in human nature: selfishness, betrayal and moral compromise. But Whittle also shows instances of tenderness amid the chaos. Some characters form bonds, attempt to atone for past wrongs or reach moments of clarity about what truly matters.

These human touches prevent the novel from sinking into cynicism, although some of the diner guests feel less fully developed than others, serving more as embodiments of moral types than as individuals. This is an issue because the story is not simply about discovering who is responsible for the deaths but about understanding why people fear the truth and how guilt and denial shape destinies.

Seven Reasons to Murder Your Dinner Guests is a clever puzzle mystery and a meditation on morality, mortality and the fragile civility that hold society together. It is both entertaining and unsettling, offering an invitation to a dinner party that will not be quickly forgotten.

For more invitations with deadly consequences, try A Novel Murder by EC Nevin and More than Murder by Jayne Chard.

HarperNorth

Kindle/Print

£0.99

CFL Rating: 4 Stars