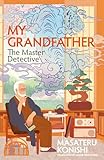

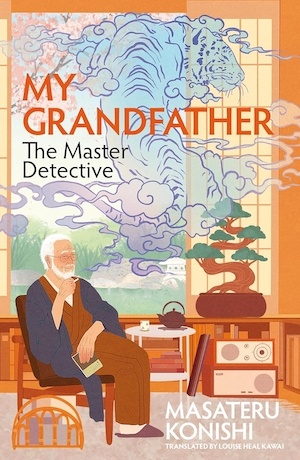

Translated by Louise Heal Kawai — Masateru Konishi’s My Grandfather, the Master Detective arrives in English translation with a lot of buzz: it’s a Japanese bestseller, winner of the This Mystery is Amazing! prize and positioned as a gentle, puzzle-focused crime novel in the vein of classic detective fiction.

It’s also Konishi’s debut novel, drawn in part from his own experiences of caring for a parent with dementia, which gives the book emotional depth that distinguishes it from lighter cosy crime. Coupled with Konishi’s knowledge of Golden Age mysteries, there’s plenty to think about even before the bodies start dropping.

Kaede, a 27-year-old teacher, finds herself surrounded by small-scale mysteries and unsettling incidents in contemporary Tokyo. Whenever she hits a dead end, she takes the case to her grandfather Himonya-san, a retired headteacher with advanced dementia and a hush-hush past with his university’s mystery club.

Outwardly frail and forgetful, he nonetheless retains an astonishingly lucid, analytical mind when a problem truly engages him. Together, the pair ‘weave stories’ to test different explanations, gradually closing in on the truth behind locked-(bath)room murders, missing persons cases and other seemingly impossible situations.

Structurally, the novel comprises six interlinked mysteries: essentially a sequence of short stories that build into a larger narrative arc. Konishi draws heavily on the Golden Age tradition, and the cases are all fair-play puzzles where small observational details or offhand remarks turn out to be crucial.

The relationship between Kaede and her grandfather forms the heart of the book, although Konishi avoids the easy sentimentality that might be expected from such a premise. He doesn’t romanticise dementia either – the grandfather’s confusion, memory gaps and moments of distress are handled with a matter-of-fact tenderness.

Given that this aspect of the overarching story draws on Konishi’s own experience of caring for his father with dementia, there is plenty of lived familiarity in the details – the repetition of questions, the small strategies family members adopt to preserve dignity, the flashes of the ‘old’ personality appearing and disappearing.

At the same time, Konishi leans into the paradox of a mind that is both failing and brilliant. The grandfather cannot reliably navigate everyday life, but give him a knotty problem and he lights up with focus and delight. That tension – between decline and capability, between the person the family now sees and the person he still is inside – is explored with a light touch.

The mysteries serve as a way for Kaede to remain connected with her grandfather despite their changing circumstances and impinging outside forces. Seeking his help with puzzles allows her to interact with him in a way where he can still be the teacher, the guide and the hero he always has been.

In this way, My Grandfather, the Master Detective sits at the intersection of traditional cosy crime and what has become a recognisable strand of contemporary Japanese fiction in translation: quiet, reflective stories about time, regret and human connection – almost like the Thursday Murder Club getting together at Café Funiculi Funicula.

The stakes of the individual cases are often serious, but Konishi’s tone is rarely grim. Even when the truth is dark, the focus remains on understanding rather than punishment. There’s an undercurrent of compassion running through matters: people make terrible choices for complicated reasons, and unpicking those reasons is just as important as determining ‘how’.

As such, My Grandfather, the Master Detective is not a book with visceral tension, and the cosy aspect is both a strength and a limitation. Konishi is very good at setting up intriguing scenarios – a locked room here, an inexplicable alibi there – but some resolutions appear overly neat or rely on emotional revelations that are more moving than shocking.

Relatedly, Kaede’s voice is straightforward and unshowy, which suits both her personality and the detective story roots of the book. She’s perhaps a bit more unflappable than she should be – for her own sake and that of others – but that’s in keeping with the reserved nature society expects and the characteristics amateur sleuthing demands.

Through Kaede’s generally inadvertent involvement in an escalating catalogue of cases, Konishi knits the domestic and the deductive. A pot of tea, a misremembered appointment, a passing remark about an ex – these are the observational crumbs that her grandfather transforms into lines of inquiry.

The grandfather’s mixture of gruffness, humour and occasional philosophical musing comes across beautifully. His condition is never used as a cheap twist – it shapes the narrative in practical ways. There are moments when his memory lapses create tension or complicate an investigation, and others when his clear-eyed insight cuts through everyone’s assumptions.

Of course, the idea that a stimulating puzzle can return a dementia patient to their previous mental state may prove a polarising one. To Konishi’s credit, he does show that the grandfather’s clarity is temporary and doesn’t magically halt his decline, but the emotional weight of the lucid detective moments sometimes overshadows the harsher realities.

The strengths of My Grandfather, the Master Detective lie in the relationship between Kaede and her grandfather, the thoughtful depiction of dementia and the affectionate nods to classic crime fiction, rather than in jaw-dropping twists. The beauty lies in ordinary, complicated people figuring out how to live as much as how to solve crimes.

For more Japanese crime fiction, try Murder at the Black Cat Café by Seishi Yokomizo and The Night of Baba Yaga by Akira Otani.

Macmillan

Print/Kindle/iBook

£8.99

CFL Rating: 4 Stars