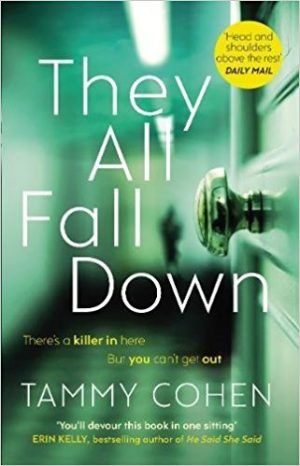

Written by Tammy Cohen — Hannah is a recent patient in a women’s low security psychiatric facility called The Meadows outside London. Why she’s there isn’t clear to begin with, apart from vague references to Hannah’s daughter Emily, but its unravelling is part of the intrigue.

Written by Tammy Cohen — Hannah is a recent patient in a women’s low security psychiatric facility called The Meadows outside London. Why she’s there isn’t clear to begin with, apart from vague references to Hannah’s daughter Emily, but its unravelling is part of the intrigue.

But the real tension comes from the fact that two of the institution’s patients have killed themselves in recent weeks. In fact, the first line is, “Charlie cut her wrists last week with a shard of caramelised sugar.” Caramelised sugar that Charlie and Hannah had made into sheets together. Sheets about which Hannah had joked, “Yours are thick enough to do yourself an injury.”

Hannah doesn’t feel guilty about this remark, though, because she doesn’t believe Charlie killed herself. She thinks both of the so-called suicides were murder, and she’s scared. But who is going to believe a patient in a mental asylum?

Most of the short chapters are told from Hannah’s perspective in the first person, or that of her mother Corinne in third person. Corinne isn’t sure what to make of Hannah’s accusations. She wants to believe her daughter, but Hannah’s done some strange things lately that weaken her credibility. At the same time, she’s desperate to believe her daughter is safe there.

And the director, Dr Oliver Roberts, and the art therapist, the supportive Laura, as well as most of the other staff, seem capable and conscientious, don’t they? Are these people who they say they are? Their contention that patients at The Meadows are high risk, with histories of suicide attempts, never quite reassures her.

A few chapters are told from the therapist Laura’s point of view, and she also has doubts about Dr Roberts. She uses artistic expression to guide her patients toward insight into their issues, and it’s interesting to see how they react to these challenges. Laura has her own challenges at home with her mother, severely disabled from a stroke.

Then there are Hannah’s fellow patients, who are an interesting bunch. Odelle is thin as a stick with serious eating disorders. Stella’s otherworldly appearance was caused by too much cosmetic surgery, including the removal of a rib for a thinner waistline. Then there’s Judith, who says she’s just being honest when she’s actually being cruel. As events unfold and confidences are shared, the patients form a kind of lamenting Greek chorus.

These characters are mostly well developed, especially Corinne, Hannah, Odelle and Stella. However, it is jarring when you realise they’re in their mid-30s. They often behave like adolescents. Perhaps it’s because of their mental disorders.

Thrown into the mix are a lurking filmmaker and his cameraman working on a fly-on-the-wall documentary. This is a nice touch – with the director Justin “doused in self-absorption like cheap cologne” – since an underlying theme of the book is perception. What does the impartial lens of the camera reveal? What do each of the characters perceive about each other, and do they trust one another’s account of things?

The writing is effective and the pace is good and varied. However, Cohen often uses cliffhangers to hook you into reading just one more chapter, and mysterious items and messages turn up in the hospital. At one point, a red baby hat appears on Corinne’s doorstep. Eventually these are all explained, but the overuse of this technique gets to become artificial.

Throughout the ordeal, Corinne tries to maintain a relationship with Hannah’s handsome husband Danny. It’s not clear that he’ll take Hannah back after what she’s done, and he seems altogether too chummy with Dr Roberts. Between them, they could determine whether Hannah leaves The Meadows or not.

Corinne’s younger daughter Meg is in New York and comments from afar. She has no use for Danny, and her criticism of him has estranged her from Hannah. Meg speaks in a jerky way, and keeps questioning why Hannah needs to be in the institution. This leaves Corinne pretty much on her own to sort things out – Hannah’s belief there’s a killer in the Meadows, her fears for her daughter, and mounting evidence that the place isn’t what it seems.

For more troubled characters, seeking help through therapy and yet wrapped up in a mystery, try Mark Billingham’s Die of Shame.

Black Swan

Print/Kindle/iTunes

£0.99

CFL Rating: 4 Stars