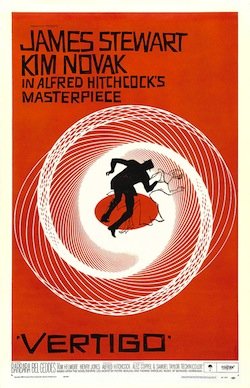

While an Alfred Hitchcock adaptation was always a coup for any author, ultimately the master’s movie tended to overshadow the book – and that is certainly the case with Vertigo (1958). Hitchcock’s psychological thriller is now recognised as one of the best films of the 20th century, although it had mixed reviews at the time and only received two Oscar nominations in technical categories. Following a critical reevaluation, it replaced Citizen Kane as the best film of all time in the 2012 British Film Institute’s Sight & Sound critics’ poll.

Hopefully, the original novel will now enjoy a similar revival as it is reissued by a new crime and mystery imprint from Pushkin Press, which has named the new series Pushkin Vertigo after the first book to appear in it. The story will be familiar to fans of the film starring James Stewart and Kim Novak, though Hitchcock transposed the book’s action from Paris and Marseilles to San Francisco.

The 1954 novel by the French writing duo Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac was originally called The Living and the Dead in its 1956 English translation, but Hitchcock’s snappier title appears to have taken over for later editions. The director had missed out on their 1952 debut collaboration She Who Was No More, so he was determined to secure the rights to The Living and the Dead. What Hitchcock didn’t know was that Boileau-Narcejac (as the duo styled themselves) had actually written the novel with the director in mind.

Like Patricia Highsmith, who had recently published Strangers on a Train (also filmed by Hitchcock) and her story of obsession The Price of Salt (also published as Carol), Boileau-Narcejac rejected both the English whodunnit and the American hardboiled styles in favour of psychological thrillers. Vertigo, to use its current title, is a perfect example of the form from this crime-writing duo who wrote together over four decades. Boileau came up with their strange and sinister plots, while Narcejac’s characterisation made the central character’s relentless nightmare seem all too real.

In Vertigo, the lawyer Roger Flavieres is driven to despair by what seems a simple job from an old college friend. “I want you to keep an eye on my wife,” says the industrialist Paul Gevigne in a first chapter that’s full of snappy dialogue and seething with undercurrents of resentment. The novel is set on the eve of World War II – several characters seem blithely confident that France will triumph – and Flavieres views the more successful Gevigne as a war profiteer, seeing as his company is signing contracts for warships. Then there’s the awkward discussion over Flavieres’s fall from grace: he left the police in disgrace after his fear of heights led to another officer falling from a roof during a chase.

It’s a death that haunts Flavieres, who’s living a listless life with his legal cases – that is until he sees Gevigne’s wife, Madeleine, for the first time in a theatre. He soon develops an obsession for the woman he’s stalking on behalf of her husband. Having witnessed her strange behaviour, Gevigne is convinced that his wife is at risk and wants his college friend to protect her from a discreet distance. Madeleine, he tells Flavieres, appears to have become possessed by a distant ancestor, who killed herself in 1865 aged 25 (the same age as Madeleine).

It’s a fanciful theory, but in her fugue state Madeleine does seem to be fixated on a portrait of this ancestor, as well as visiting her grave and locations known to the long-dead woman almost a century earlier. When, early in the book, she stages a suicide bid, Flavieres rescues her and discovers the full extent of her bewitching by the dead woman. “It doesn’t hurt to die,” Madeleine tells Flavieres when he pulls her from the water. She’s convinced that she already died in 1865 and is being lured back to the other side.

It’s a bizarre beginning yet Flavieres’s case is given credulity by further events and conversations as he falls in love with Madeleine, while his own psychological fragility takes a further knock. Although it was the character’s fear of heights that inspired the film’s title, the novel also focuses on Flavieres’s fixation on death. He describes a lonely childhood in Saumur in western France, where he was haunted by its underground caverns and drawn to Greek mythology – the story of Orpheus and his wife Eurydice in the Underworld had him “shivering with the chill of death”. Decades later he finds his own Eurydice in Madeleine, who’s also lured to the Underworld.

Unless you’ve already seen the film, this story of obsession, deceit and human frailty has an almost overpowering intensity. Flavieres may be gripped by madness and burgeoning alcoholism, but there’s a chilling clarity in his wayward quest for spiritual truth. Even if you are familiar with the classic movie, the novel has key differences: halfway through, the story leaps forward four years as every French person’s life is torn apart by war. In a short novel, it’s audacious storytelling in which personal tragedy mirrors a national conflict. While the eventual solution may seem a little bit too neat (perhaps with Hitchcock in mind), it’s the haunting prose that stays with you long after you’ve finished this French classic.

Alongside Patricia Highsmith and French writer Pascal Garnier, the writing duo Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac deserve recognition as part of the great tradition of chilling psychological crime fiction.

Vertigo is reissued by Pushkin Vertigo in paperback and eBook on 17 September. She Who Was No More is published on 5 November.