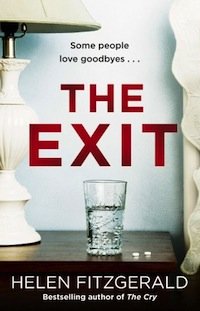

The Exit is a psychological thriller with a fixation on death, though one principal character has to negotiate the maze of dementia before she’s able to reach her final destination. Rose Price is a children’s author and illustrator, though she’s now struggling to write those stories. At 82, she’s been diagnosed with dementia and has moved into the Dear Green care home in Glasgow. While drawing pictures that make little sense, she mentally travels between the present and a wartime tragedy involving her younger sister 72 years earlier.

At first, The Exit appeared to be a case of bad timing. Six months after Emma Healey’s excellent debut, Elizabeth is Missing, it seemed as if FitzGerald had also published a mystery in which a dementia sufferer negotiates the fog of this disease to find the truth about her sister several decades earlier. But while Rose may be haunted by guilt over her actions in childhood, the shocking crimes in The Exit occur in the present day and are facilitated by the internet.

It takes some time to establish what crimes are actually being committed. For the first third of the novel, Fitzgerald lays a few false trails and takes time establishing her main characters: Rose and Catherine Mann, a flighty 23-year-old who’s addicted to social media and unsure what to do with her life. Her mother, a charity director, wants to organise it for her with a series of self-improving objectives compiled in daily lists that infuriate Catherine. As Catherine considers a post-graduate course, her mother fixes her up with a temporary job at the care home where Rose resides.

FitzGerald switches between the confused interior monologue of Rose and the sardonic narrative from Catherine as the crimes at the care home begin to emerge. The pair quickly form an unlikely bond that bridges the generation gap. Catherine describes the opinionated writer as an 82-year-old punk, while Rose forces the arrogant younger woman to find some humility and honesty. But it’s still not clear what wrong is being done at Dear Green, if any. Rose’s allegations about evil in the care home are taken to be the confused ramblings of an old woman, though her illustrations seem to hold clues about what might be going on in room seven.

In this lean story of domestic suspense, FitzGerald is not afraid to let recognisable human drama intrude. Catherine has an awkward relationship with her mother, a single parent and – in her daughter’s eyes – a relentless do-gooder, though events bring about a touching reconciliation. It also adds to the tension as family concerns distract Catherine from what might be going on with the care home and its odd residents: a husband and his catatonic wife, a former musician with a shady past, and the owner who lives upstairs and claims to be writing a crime novel. When she finds a logbook containing lingering accounts of the deaths of former residents, Catherine enlists the help of a social worker who was previously involved with Rose’s care.

FitzGerald is a social worker herself and she understands that crimes are often committed by ordinary people, which makes The Exit such a suspenseful read – any one of these characters might be guilty of something. She also succeeds in making Rose a heroic woman and not merely an aged victim of a horrible disease.

There are also some self-aware touches in this novel, including a dig at genderless crime writers with the portrayal of an irksome local author who only uses her initials in the hope of selling more books to readers who might not buy a gritty procedural written by a woman. Thanks to the complementary voices of Catherine and Rose, The Exit is often darkly comic, which is just as well as it gallops towards a horrific finale that’s effective if a little far-fetched.

In many ways, though, this is a perfect psychological thriller – smart, funny and ultimately very disturbing. But it probably won’t be for everyone, especially if you like your crime writing to feature a strong sense of place, prose that relies on lingering descriptions and actual cops solving clear-cut murders.

The Exit is published as an ebook on 3 February and paperback on 5 February.

Faber & Faber

Print/Kindle/iBook

£4.19

CFL Rating: 4 Stars