Captain Gregor Reinhardt won the Iron Cross while serving in the trenches with the German army in World War I. After a spell between the wars where he became one of the best detectives in Berlin’s Kriminalpolizei, he has reluctantly accepted a commission in the Abwehr, the German army’s military intelligence branch. He has earned respect with the thoughtful and perceptive techniques he uses when interrogating enemy prisoners. He gets the right answers without resorting to the brutal techniques beloved of his comrades in arms, the SS.

It is 1943, and Reinhardt is operating in the most complex and confused theatres of the European war – The Balkans. The city of Sarajevo, formerly the capital of Bosnia Herzegovina, is now in the Independent State of Croatia. The Axis powers – Germany and Italy – have established an uneasy rule, but resistance comes in many forms, not the least being from the Partisans and the Chetniks. Against this turbulent background, Reinhardt investigates a double murder. He finds the brutalised corpse of Marija Vucić, a beautiful but predatory woman who became Yugoslavia’s version of Leni Riefenstahl with her propaganda films and photographic essays. In the next room is the dead body of Lieutenant Stefan Hendel, one of Reinhardt’s Abwehr colleagues.

Reinhardt doggedly seeks the truth, blocked at every turn by the Sarajevo civilian policeman Padelin, his own German military police the Feldengarmerie, and most menacing of all, the fascist terrorists of the Ustaše movement. Reinhardt’s sleep is racked with dreadful dreams about his life in the trenches, and visions of his dead wife. His waking hours are a mixture of determination to do what is right, self-preservation in the face of provocation, and the occasional outburst of terrible violence. The latter confirms his status as a man who should be respected, but also feared when the black rage takes him over. When all leads seem to point to a culprit right at the centre of the German military command, Reinhardt is forced to pursue his quarry far from the boulevards of Sarajevo and deep into the mountains where the German army, along with their Italian and Ustaše allies, are attempting to destroy the guerilla Partisans and their leaders. What he finds there completely turns on its head his assumption about the motives behind the deaths of Vucić and Hendel.

Without suggesting that the book is in any way diminished as a result, it must be said that there are many similarities between Reinhardt and the other well-known German policeman, Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther. Both men are veterans of The Great War. Both served with the Kripo in Berlin. They share the same sorrow at the death of a wife, and both have a distinctly ambiguous relationship with the many conflicting groups within the German military/political system. There are differences, though. Reinhardt is much more at the mercy his inner demons than Gunther; he is far angrier and he doesn’t do wisecracks.

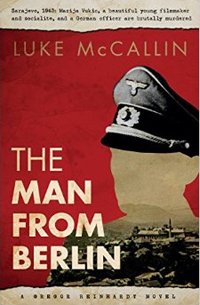

The Man from Berlin works well on many levels. Those who like their political history will find this a fascinating exploration of the ethnic, religious and cultural divisions which made The Balkans one of the world’s most unstable regions throughout the 20th century – a situation which still exists today. Readers who enjoy crime fiction, pure and simple, will appreciate what is a clever combination of a locked-room mystery and a whodunnit. For lovers of elegant prose, convincing dialogue and perceptive characterisation, there is also much to admire. The verdict? A gripping second novel from a gifted writer.

No Exit Press

Print/Kindle

£4.28

CFL Rating: 5 Stars