“The city in these pages is imaginary. The people, the places are all fictitious. Only the police routine is based on established investigatory technique.”

“The city in these pages is imaginary. The people, the places are all fictitious. Only the police routine is based on established investigatory technique.”

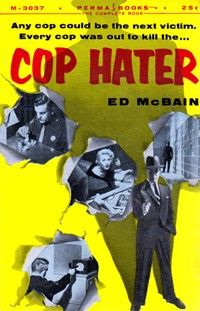

It’s just 24 words, but no three sentences have ever held so much significance on the flyleaf of a book. Each of the 54 novels in the 87th Precinct series by Ed McBain begins in this way (well, 55 if you count a cross-over novel with another character). Cop Hater, with its no-nonsense title, was first published in 1956, and with it McBain helped shape the police procedural sub-genre.

Ed McBain was born Salvatore Lombino in 1926, and died in 2005. Before the 87th Precinct series, he’d already written the 1954 bestseller Blackboard Jungle under the pen name Evan Hunter. He also wrote the screenplay for Hitchcock’s 1963 film The Birds. “I usually start with a corpse,” he once said, describing the 87th Precinct books. “I then ask myself how the corpse got to be that way and I try to find out – just as the cops would.”

Cop Hater established this simple but effective template. The city is never named, but it is New York, and if you’re inclined to do so you can match McBain’s topography with that of the city as you read. There is a stifling heat as the story opens. Ceiling fans are worse than useless, and people all over town are wondering if they can afford air conditioners. Detective Mike Reardon is on the midnight shift. He kisses his drowsy wife goodbye and peeps in on his children.

Minutes later, two shots ring out and Reardon is face down on the sidewalk. Stone dead. Detectives Steve Carella and Hank Bush of the 87th Precinct arrive on the scene. They turn the body over and are horrified to recognise the face of a fellow cop. “He used to be a cop and a friend. Now he’s a victim and a corpse,” says Bush in that plain cop-speak that marks out dialogue in the series.

Minutes later, two shots ring out and Reardon is face down on the sidewalk. Stone dead. Detectives Steve Carella and Hank Bush of the 87th Precinct arrive on the scene. They turn the body over and are horrified to recognise the face of a fellow cop. “He used to be a cop and a friend. Now he’s a victim and a corpse,” says Bush in that plain cop-speak that marks out dialogue in the series.

While the detectives try to trace the owner of the .45 that killed Reardon another detective, David Foster, has the life ripped out of him by four bullets from the same weapon. Carella and Bush chase down a succession of leads, but then Bush, who is worried about his voluptuous wife Alice, is also gunned down. A terrible truth dawns on Carella.

By the time the series came to a close in 2005, McBain had created an impressive and beautifully drawn cast of characters. Cop Hater gives us a glimpse of players who’d later become veterans in the author’s storylines. Bert Kling is just a uniformed patrolman here, but Lieutenant Pete Byrnes is already a grizzled, teak-tough cop. Havilland and Willis make fleeting appearances, as do the deadly duo homicide cops Monaghan and Monroe. We also meet the lovely Theodora, or Teddy, the deaf mute girl who later marries Carella, bears his children and plays a supreme supporting role in future novels.

Of course, he added further characters in later books. Watch for Fat Ollie Weeks, for instance. In 2002 McBain wrote a novel that was actually entitled Fat Ollie’s Book – Ollie is unreconstructed, obese, and a bigot, but as we also discover he is a fine cop. And let’s not overlook McBain’s most memorable villain – The Deaf Man. Often the nemesis of Carrella and his buddies, you’ll meet him in The Heckler (1960), Eight Black Horses (1985) and Fuzz, the film shot in 1972 and starring Burt Reynolds as Carella and Yul Brynner as The Deaf Man.

Of course, he added further characters in later books. Watch for Fat Ollie Weeks, for instance. In 2002 McBain wrote a novel that was actually entitled Fat Ollie’s Book – Ollie is unreconstructed, obese, and a bigot, but as we also discover he is a fine cop. And let’s not overlook McBain’s most memorable villain – The Deaf Man. Often the nemesis of Carrella and his buddies, you’ll meet him in The Heckler (1960), Eight Black Horses (1985) and Fuzz, the film shot in 1972 and starring Burt Reynolds as Carella and Yul Brynner as The Deaf Man.

Critics will point to McBain’s formulaic writing – that is bound to happen in a series lasting 49 years – but frequently his prose is brilliant. In terms of length, the 87th Precinct stories aren’t much more than novellas, but there is a wonderful rhythm to McBain’s style. It rides the waves of terse dialogue and compassionate descriptive passages. We learn about procedure in detail. There are even facsimile charge sheets and police records printed in the pages of the books. The policemen sweat and swear in the heat, and their cheap suits crumple. When they enter apartments pursuing their quarry, we breathe the smells as the sounds of humanity hammer our eardrums.

The 87th Precinct is said to have been influenced by the radio and TV series Dragnet, which itself was ground-breaking. It turned away from the melodrama of post-war private eye stories to focus on day-to-day police work. From Hill Street Blues in the US to The Bill in South London, cop shows, movies and police procedurals owe a debt to McBain. Although the writer himself was less than positive about Hill Street Blues, it cut a wake for further gritty copy TV like NYPD Blue, Homicide and arguably even The Wire. And we know that gave rise to current favourite authors like George Pelecanos and Dennis Lehane.

For more on police procedurals, click here, and you can watch the 1972 theatrical trailer for Fuzz below: