Classics in September — “I always thought it would be better to be a fake somebody than a real nobody.” – Tom Ripley.

Classics in September — “I always thought it would be better to be a fake somebody than a real nobody.” – Tom Ripley.

Okay, so Anthony Minghella put those words into Ripley’s mouth for the 1999 film adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s novel The Talented Mr Ripley, but in writing them he cut straight to the core of Highsmith’s brilliant, amoral psychopath, a character who could have as easily been the creation of Camus or Dostoevsky, and who was to dominate Highsmith’s thinking to such a degree through the years that she was occasionally known to sign letters off with his name.

Born in Fort Worth, Texas in 1921, Highsmith’s early years were marked by family upheaval. Her parents’ divorce when she was 10 took her to New York and back to Texas again, as she was shunted between relatives, creating an uneasy relationship with her mother which was never to recover. Famously she claimed her mother drank turps to try and abort her. As a child she became fascinated with the psychology of aberrant behaviour and displayed signs of it herself as an adult. The Price of Salt – a lesbian novel, published under a pseudonym – was inspired by a woman she encountered while working at Bloomingdales and subsequently stalked after acquiring her address from credit card details.

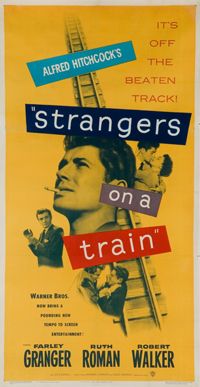

In 1951 Highsmith’s debut Strangers on the Train was released and swiftly picked up by Alfred Hitchcock, who kept the skeleton of the story but couldn’t quite do justice to the claustrophobic, co-dependant relationship at the heart of the book. It’s a theme which Highsmith would come back to time and again throughout her long career – two men locked together by murder, the alpha and the beta apparently clearly defined but poised for subversion, frequently underscored with hints of homoeroticism and sadomasochism. Four years later, with The Talented Mr Ripley, she took these elements and produced a crime classic.

In 1951 Highsmith’s debut Strangers on the Train was released and swiftly picked up by Alfred Hitchcock, who kept the skeleton of the story but couldn’t quite do justice to the claustrophobic, co-dependant relationship at the heart of the book. It’s a theme which Highsmith would come back to time and again throughout her long career – two men locked together by murder, the alpha and the beta apparently clearly defined but poised for subversion, frequently underscored with hints of homoeroticism and sadomasochism. Four years later, with The Talented Mr Ripley, she took these elements and produced a crime classic.

The book opens with Ripley ducking into a bar away from a man he suspects to be some kind of detective, pursuing him over one of the small grifts he has been living off, but the man has an entirely different motive. Mr Greenleaf has a problem with his son Dickie, who’s taken off to Europe and refuses to come home and face the responsibilities associated with his father’s money. Mistakenly believing the two of them to be friends he asks Ripley to go to Italy and try to persuade Dickie to return home.

Dickie Greenleaf, handsome, carefree and self-assured in a way that only the born-rich ever are, represents everything which Ripley isn’t and being so close to this gilded bohemian inspires a roiling blend of adoration and envy in him. Ripley charms Dickie, amuses him with impressions and a certain gaucheness which the alpha-male Dickie enjoys ridiculing, finally earning his trust by admitting that their meeting was no chance encounter, but rather stage managed and funded by Mr Greenleaf. The bond is sealed but, this being Highsmith’s writing, it has to break.

Dickie quickly tires of Ripley. He doesn’t belong in that world and even a chameleon nature and a sharp mind can’t hide the fact that he’s a parasite. But Ripley has grown accustomed to Dickie’s lifestyle and it holds an attraction much more persistent than the man himself. For Ripley there is only one course of action, murder Dickie and take his place. Highsmith presents the act as inevitable and we follow Ripley’s breakneck machinations as he tries to elude the police, slipping between Dickie’s identity and his own in order to fend them off. And we want Ripley to get away with it. Like Dickie we are charmed by him and we want to see him succeed.

Ripley should be a repulsive character, he’s cold and calculating, utterly without remorse, but Highsmith knew how to push her readers’ buttons. By placing us so completely inside Ripley’s head and viewing the world solely through his eyes she makes his actions seem if not just, then understandable. We sympathise with his poverty at the outset and his loneliness as he considers the tattered remnants of his family, the envy he feels for Dickie and the anger/shame/despair when he is rejected. These universal experiences tie the reader to Ripley’s predicament and make it very easy to come around to his way of thinking.

Ripley should be a repulsive character, he’s cold and calculating, utterly without remorse, but Highsmith knew how to push her readers’ buttons. By placing us so completely inside Ripley’s head and viewing the world solely through his eyes she makes his actions seem if not just, then understandable. We sympathise with his poverty at the outset and his loneliness as he considers the tattered remnants of his family, the envy he feels for Dickie and the anger/shame/despair when he is rejected. These universal experiences tie the reader to Ripley’s predicament and make it very easy to come around to his way of thinking.

Highsmith’s writing is spare, almost clinical, with no purple prose or literary pyrotechnics, and this pared back style is perfectly suited to the amorality of her characters, not just Ripley, but the cast of middle class murderers, stalkers and adulterers who populate her other books. By now we’re accustomed to white collar psychopaths and the idea that something unpleasant is always lurking behind a respectable facade, but when The Talented Mr Ripley was released these were genuinely original concepts, and Highsmith was a mistress of the stripped veneer.

The later instalments of The Ripliad are slightly uneven in my opinion. Ripley remains as fascinating as ever and seeing this genial psychopath settled in a French rural idyll, with a flighty wife and bourgeois neighbours, makes them worth reading, but the plots occasionally stretch credulity. The Talented Mr Ripley is the major work in Highsmith’s oeuvre and a significant piece of 20th century crime fiction which you owe it to yourself to read.

Great write-up, Eva. I absolutely love the film of this but haven’t read the book yet, even though I used to have a copy hanging around (since lost).

It reminds me of my favourite book, The Secret History, and I wouldn’t be surprised if Tartt was influenced by Ripley, who is similar to Richard in the way he is a poor boy who pretends to be rich, infiltrating that world, always under threat of exposure. It’s a very appealing idea.

I bought this book years ago and marinated it for a decade. When I finally got to it, the laconic poetry from the mind of Highsmith’s narcissistic killer just floored me. Having traced or defended people like this in my everyday profession, her portrait of Mr. Ripley resonates as true, accurate and disturbing. And the book is set in some great locales to boot. D

The Talented Mr. Ripley deserves to be on anyone’s short list of great crime fiction. Thanks Eva, for a revisit to Mr. Ripley; and good point on the series: the other Ripley books for some reason lack the malevolent brilliance of the original.