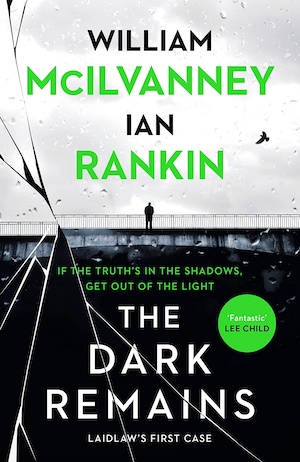

Laidlaw’s first big case. When William McIlvanney died in 2015, the importance of his Laidlaw novels to Scottish crime fiction was just beginning to be properly recognised. He’s now rightly seen as the godfather of Tartan noir. Intriguingly, McIlvanney left behind a half-written manuscript for a new Jack Laidlaw mystery and at his estate’s behest Ian Rankin took up the challenge of completing the novel for publication. The Dark Remains is a prequel to the existing Laidlaw trilogy. It is, of course, set in Glasgow, which is as much the beating heart of the series as its protagonist, Jack Laidlaw.

As Rebus was conceived as the Edinburgh Laidlaw, Rankin was well suited to the task, understanding McIlvanney’s character, his values, contradictions and complexity perhaps better than anyone else. The Dark Remains presents a slightly younger Laidlaw than that of the original trilogy and the story takes place in 1972. Laidlaw is just a detective constable at this time. He’s a misfit who doesn’t make fiends easily but when it comes to the nitty-gritty of crime solving he has a rare instinct and the courage of his convictions, or bloody-mindedness depending on your perspective, to see it through.

It’s October and Commander Robert Frederick is musing on crime in the city. Philosophical openings are de rigueur in Laidlaw. Unless it affects you personally, you ignore crime and tragedy, occasionally picking up on the story of Bible John or the terrible Ibrox stadium disaster. See it or not it’s there, just look hard enough. Two things in particular are weighing on Frederick; the disappearance of Bobby Carter and the appearance of the new guy on the squad, Jack Laidlaw. Carter, a lawyer working for gangland boss Cam Colvin, is into everything the dirty underbelly of the city has to offer. It’s been two days since he went missing. If Carter is dead that leaves a vacuum which could lead to a street war with rival gangs, run by John Rhodes and Matt Mason. As for Laidlaw, Frederick decides to make Detective Sergeant Bob Lilley his minder.

Laidlaw is a good policeman, he knows the streets, but he rubs others up the wrong way. He’s had a lot of jobs over the years because of that. As it’s the end of the day, Lilley’s first task is to take Laidlaw to Ben Finlay’s leaving do to introduce him to the team. Incidentally, the drinks are courtesy of John Rhodes – it’s one of his places. Lilley is trying to gauge Laidlaw’s character. He’s not a mixer and he seems to have some problem with DI Milligan, likely his new boss once they get a case. Clearly the two have history. Laidlaw tells Lilley he thinks Milligan is an idiot, in love with the uniform and its power – any uniform, a bit of a fascist. Lilley susses this is not going to be easy but Laidlaw doesn’t have a high opinion of much to do with his job:

“The law’s not about justice. It’s a system we’ve put in place because we can’t have justice.”

Conn Feeney owns The Parlour, a run-down dockside pub on Rhodes turf, which means the gangster is either a silent partner or taking a slice in protection. A young couple sneak off for a snog only to discover a body in the lane beside the pub. Feeney hesitates before calling the cops – it’s Bobby Carter, Colvin’s man, he knows the trouble this will bring. Frederick assigns Lilley and Laidlaw the initial investigation of Bobby Carter’s death, throwing his new charge in at the deep end. Milligan will have overall command by morning.

It’s obvious someone is sending a message but how was Carter lured into Rhodes territory to be killed, surely he was smarter than that. Lilley and Laidlaw decide to rattle cages starting with Carter’s boss Colvin before tackling the other two gangsters. Colvin also knows this is a message. He sends his boys to find out who from, when he gets an answer all hell will break loose. The first lead is a rumour that Carter was a womaniser and that he was seeing Chick McAllister’s woman, Jennifer Love. McAllister works for Rhodes. Jenni is a girl who likes a good time and likes men with the money to pay for it but seeing blokes from rival gangs is pretty risky. Laidlaw intends to go his own way, meanwhile violence escalates across the city.

There are a couple of familiar Rankin traits in this novel and his style works well for the modern audience. Crucially, this is achieved without losing the essence of McIlvanney’s character or the philosophical musing, the hard edged look at Glasgow in tough times that underpinned the original trilogy. This is set in the 1970s so there’s more social commentary than in recent Rebus novels, these are times heavy with working class angst, misogyny, corruption and bigotry. Rankin is as strong on the compassion for the characters and their plights as McIlvanney was and there are plenty of keen observations on Glasgow people.

Neither Rankin nor McIlvanney has ever been short on wit and that comes across in the sharp dialogue. The references to Carter as a consiglieri echo The Godfather – the film came out in August 1972. In the novel Laidlaw we were told that he and his wife Ena live separate lives within their marriage, in The Dark Remains we see the split growing. Laidlaw is a loner.

What happens in The Dark Remains fits so well with the existing novels this can now legitimately be called a quartet. The portrait of the city is vintage McIlvanney and Laidlaw is Laidlaw – square jaw, broad shoulders, “…life had already subjected him to a harsh interrogation.” There are moments of poetry in McIlvanney that Rankin doesn’t try to match but this is a really satisfying crime novel, intelligent and gripping and very much in keeping with the spirit of the original, a superb read.

For an overview of the Laidlaw series read our primer here.

Canongate

Print/Kindle/iBook

£11.99

CFL Rating: 5 Stars