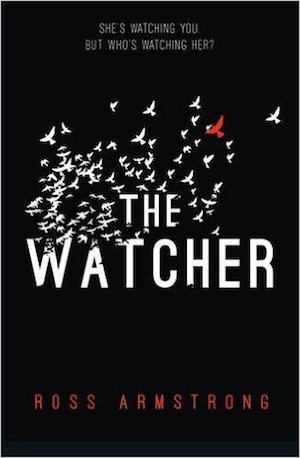

Written by Ross Armstrong — Hitchcock looms large over this debut novel. A striking cover evokes The Birds and the initial premise is a post-modern twist on the 1954 film Rear Window. Our hero with a pair of binoculars is Lily Gullick. She is a bird watcher, a twitcher, but she spends most of her time on her balcony watching her London neighbours in the flats opposite. She sparks up a brief relationship with an older woman, Jean, from the neighbouring flats. The flats are already condemned and Jean is then murdered. Unlike in Rear Window, Lily has no immediate suspects for the murder but she starts investigating in her own style.

Written by Ross Armstrong — Hitchcock looms large over this debut novel. A striking cover evokes The Birds and the initial premise is a post-modern twist on the 1954 film Rear Window. Our hero with a pair of binoculars is Lily Gullick. She is a bird watcher, a twitcher, but she spends most of her time on her balcony watching her London neighbours in the flats opposite. She sparks up a brief relationship with an older woman, Jean, from the neighbouring flats. The flats are already condemned and Jean is then murdered. Unlike in Rear Window, Lily has no immediate suspects for the murder but she starts investigating in her own style.

Lily narrows the list of suspects as she voyeuristically charts the movements of the occupants of the flats. Naming them after Hitchcock’s actors, the antics of Tippi, Janet and Cary fill her lenses. Lily is living with her husband, Aiden, who is absorbed in writing his novel so she engrosses herself in the investigation. She soon realises that her observations aren’t enough and with the help of some locals she ventures out to take more direct action. This is more risky and her behaviour and mood swings soon become erratic and unpredictable.

The Hitchcock references come thick and fast and are initially almost overwhelming. In the first few pages I was spending more time puzzling over cryptic allusions to the director’s oeuvre than taking in the story. However, within a couple of chapters you’ll be immersed in the world viewpoint of Lily. Each chapter starts with brief notes that emulate a birdspotter’s diary. Again, this can be distracting and the story holds up on its own without needing any devices. Armstrong does throw in some further overt nods to Hitchcock throughout the plot but it is also blackly comic.

The social background to this novel touches on the intersection of gentrification and urban degeneration. Lily recognises the inequalities and she feels the vague guilt of the ‘haves’ spectating on the ‘have-nots’. There is no underclass perspective in this book but it is not attempting to be a searing social commentary. Neither are these heavy handed or token attempts to add superfluous background colour. The portrayal of the social milieu adds depth to the narrative and we walk with Lily as she attempts to create simple human connections.

Hitchcock held back information from the audience and his own characters to build tension and Armstrong has clearly been studying the master of cinematic suspense. The pressure builds effectively but it is driven by the narrative disintegration as our confidence in the narrator, Lily, crumbles. This is another psychological thriller where an unreliable narrator is a key element in the story. Hitchcock once said that drama is life with the dull bits cut out. In this book, as is the current vogue, drama is life with the important bits left out. It is effective but you have to put yourself in the author’s hands and trust he will deliver.

And deliver he does. Armstrong lifts the pace as we dash towards the conclusion. There are points when the problems with Lily’s state of mind stretch and test your engagement with her. On occasions it is more disorientating than intriguing and a few readers may drop by the wayside as their patience is tested. However, underpinning the story is the likeable character of Lily who is vulnerable and damaged. Like any good book, the depth of feeling for the main character is paramount and I was rooting for Lily all the way. The Watchers has a distinctive and original voice that offers a twisty and tense homage to Hitchcock.

The Watchers is released 29 December. For another interesting book inspired by Alfred Hitchcock, try What You See in the Dark by Manuel Munoz.

Harlequin Mira

Print/Kindle/iBook

£12.08

CFL Rating: 4 Stars