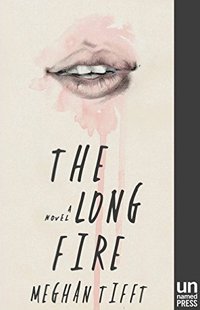

Meghan Tifft works in the English Department at the University of Colorado in Colorado Springs, and has extended her linguistic abilities by penning a new crime novel. The Long Fire comes out on 11 August and features an unusual character in smart-ass loner Natalie Krupin. Beginning with a cryptic voicemail message, The Long Fire is really about how Natalie tries to solve some of the bigger mystery in her family. It takes a literary approach to detective fiction and is set in good old New England – Worcester, Massachusetts to be precise. Natalie, who suffers somewhat from a strange desire to eat inedible substances like chalk and ash, also explores a gypsy enclave nearby, the community in which her mother grew up. We invited author Meghan Tifft to discuss the book in more depth here on Crime Fiction Lover…

What is it about The Long Fire that you hope will appeal to crime fiction lovers?

The Long Fire is a kooky riff on the detective novel, with an unwilling and unlikely detective who is trying to solve the riddle of herself as much as uncover the truth about her mother’s death and her family’s secrets. I hope readers find it an exciting and unusual take on some of the genre conventions! I wanted Natalie to struggle through a mystery that would deeply challenge her character – so as she unravels her family’s secrets she can grow and evolve in her awareness and emotional maturity too. Part of this is leaving Natalie with a few lingering questions at the end, because her growth as a character is more realistic and she can take more ownership of it if she still has mental and emotional work to do. For example, I wanted Natalie’s brother Eliot’s character to remain a bit mysterious and elusive and Natalie’s sense of where she stood with him to be unclear to her.

Natalie is a unique character in so many ways. Can you tell us more about her?

She certainly is unique, but I hope that her quirks reflect a deeper humanity that readers can find relatable. Her habits with thrift-store shopping, using kids’ furniture, and self-infantilizing all came out of my exploration of her pica and control issues arising from her childhood. To me they seemed like an authentic and necessary expression of her character.

Natalie seeks control over her issues and also wants to defy her position as victim, but her way of pursuing that control and proclaiming that defiance is rather self-defeating—and partly she knows it and feels absurd for it. She embraces absurdity because on some level she’s aware of this, and humor is her attempt to enter that awareness, but this tends to amplify all of her original issues further.

Natalie is desperate for love but has no nurturing, consistent experience of it—love in her experience is tumultuous and mixed in with a lot of negative “attention”—and she’s stuck in this rut of conflating the two. A lot of the absurd elements come from this.

Natalie has pica – an abnormal desire to eat substances not normally eaten. Why did you give her this strange affliction?

Natalie’s pica was my way of discovering her character – the delicate balancing of her vulnerabilities and needs and loneliness against her abrasive charm and admirable perseverance. It was an immediate physical struggle that grounded and individualised her for me, that made her intriguing and sympathetic and a little wacky. It gave her vigour as a protagonist and it gave the novel a kind of manic energy that propelled me (and Natalie) through the plot. She sort of chews and gnaws her way to the truth of the mystery, both going forward clue by clue in the present action and also backward memory by memory into her family’s past.

Pica also represents a constant struggle between acceptance and rejection for Natalie, between what she takes in and what she resists, what she submits to and what she refuses, and in this way it’s about her constant struggle with self-destruction and self-determination, and how that relates to her sense of belonging and exclusion, and the painful process of both turning inwards and turning outwards toward the world and putting those two experiences together and persevering. I think everybody struggles with this, so while pica is unusual I hope that the struggles it explores are universal.

The title is appropriate because The Long Fire has plenty of fires in it. What purpose do they serve?

Fire and water balance each other in the novel, and both are meant to carry many resonances in the plot, characters, and themes. They operate as literal, physical pressures that put characters at risk and in danger, creating suspense and momentum for the plot; they operate as sources of conflict between characters, intensifying relationship tensions; they operate as experiences remembered by individuals and absorbed collectively by families and the gypsies, specifically; and they operate as metaphorical ways for characters to understand the larger mysteries of their lives and their destinies.

Fire and water are both catastrophic forces of creation. They are huge and beyond us and yet they are also inside us and around us all the time in very ordinary ways. Nature models for us the danger and glory that is inherent in the combination of power and indifference. Natalie’s mother is metaphorically linked to both fire and water, and to both power and indifference – as a mother, as a creator who is responsible to her own creations, and as somebody who is herself trapped by the larger forces that shaped her. She is a deeply flawed, catastrophic creator.

The novel also explores the destructive aspects of fire – the way it ravages, desecrates, entraps, and metaphorically the way people burn with negative energy and destroy each other. But I also wanted to explore how it creates a kind of painful renewal. Destruction by fire in the novel is meant to be sometimes liberating and cleansing, offering a break or release from existential entrapment, setting a new course, but always within a larger cycle. In some places fire is treated as luck/opportunity, and in others it’s a kind of fate/fatalism. There is terrible fallout from fire, but fire is explored as a creative force too.

Human passion, human will, human love and connection are all gifts that we receive at birth and have the capacity and responsibility to nurture, and that are often warped for us and by us starting at an early age. Instances of these in the novel are often linked descriptively to fire and flame.

Setting part of the story in the gypsy family and community provides an opportunity to explore their non-conventional worldview. Are readers to trust what the gypsy characters tell Natalie?

The answer is both yes that we can trust them and no that we can’t. They’re coming from their own set of complicating circumstances. They’re meant to be authentic yet somewhat elusive characters, people whose experience has marked them and influenced their perspective and behaviour – all of them earnest and sympathetic but not always, and not completely, honest in their perspective. I think everybody in the novel lies a little.

Are you working on your next book?

I am! Very early stages. I’ll have to keep a closed mouth on specifics, but I can promise new personal mysteries and a very different dose of oddball-ism!