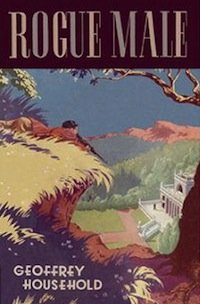

Geoffrey Household’s most famous novel is a period piece that exerts such a powerful grip on the contemporary reader it may well be the best crime thriller to be published in 2014. Rogue Male was reissued this summer to mark the book’s 75th anniversary.

Twelve years earlier, this unrelenting story about an English aristocrat being pursued by resourceful foreign agents was published as part of the Crime Masterworks series alongside Dashiell Hammet, Arthur Conan Doyle and Jim Thompson. Its classic status was affirmed last year by the publication of a handsome Folio Society edition.

Without the masterpiece of suspense that is Rogue Male, we may not have had James Bond, The Day of the Jackal or even Rambo. David Morrell, whose thriller First Blood spawned the Stallone movie series, has acknowledged the influence of Rogue Male. Household’s book was filmed by Fritz Lang in 1941 (as Man Hunt) and there was a 1976 TV movie starring Peter O’Toole, but the novel is far superior.

The opening lines are highly intriguing and offer a glimpse of the nonchalant protagonist, who is rarely out of danger for the following 180 pages. The book begins: “I cannot blame them. After all, one doesn’t need a telescopic sight to shoot boar and bear; so that when they came on me watching the terrace at a range of 550 yards, it was natural enough that they should jump to conclusions. And they behaved, I think, with discretion.”

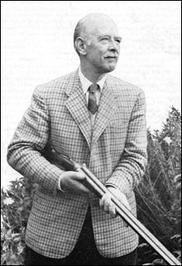

This stiff upper lip was typical of fictional British heroes of this era, though Rogue Male has endured thanks to its stylish prose and the psychological insight the author brings to a man who’s hunted like an animal. It is much more sophisticated than literary antecedents such as John Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps and Sapper’s Bulldog Drummond. Perhaps the colourful past of Geoffrey Household (1900-1988) played a role in the novel that made his name. Educated at a public school and then Oxford, he worked in banking in Romania, as a banana salesman in Spain, and a radio scriptwriter in the US.

Killing Hitler

When Rogue Male was first serialised in the summer of 1939, Household’s novel was highly topical. The unnamed narrator is an aristocratic sportsman on a shooting holiday in Poland, who decides to tackle a bigger challenge than wildlife. With that rifle and telescopic sight, he describes how he stalks and lines up a European dictator in his sights at a heavily guarded country estate.

What’s his motive? It’s not clear that he actually intends to assassinate this despot. It seems the rogue male simply wants a bit of sport by proving that he could do it. “It is obvious that the type of man who is a really fine shot and experienced in the approaching and killing of big-game would shrink from political or any other kind of murder,” the narrator tells us. However, as the novel progresses we discover that this apolitical premise may be masking a deeper anxiety about the foreign regime.

His despotic prey is, like the narrator, never named, and the absence of identities makes for a lean and uncluttered narrative, as well as an ingenious ending. From the geography and the viciousness of the secret police, it’s clear that the dictator is modelled on Hitler – and Household was apparently no supporter of appeasement. He later wrote that Hitler inspired his story of an assassin because “the man had to be dealt with, and I began to think how much I would love to kill him.” During World War II, Household served in British Intelligence. His book was published in a Services and Forces edition as a morale booster for British troops soon after the outbreak of war.

This tough thriller certainly showed its readers how one man could make a stand against evil, although the rogue male is tested beyond the limits of human endurance from the very beginning. Having captured the apparent assassin, the secret police torture him but find no evidence of his being a British agent (because he’s not). To maintain diplomatic relations with Britain – the story is firmly set in the pre-war period – the rogue male has to be dispatched in such a way that his injuries are not suspicious. So this book begins with a cliffhanger – literally. He’s left clinging to a rock face, with the intention that his inevitable death be reported a few days later as a hunting accident.

Somehow, he survives but it’s at this point the unnamed protagonist starts to transform into something as much animal as human, who can only escape by returning to nature. Household describes his character’s broken body in the marshy landscape as if writing a horror novel: ‘There was a pulped substance all around me, in the midst of which I carried on my absurd consciousness. I had supposed that this bog was me; it tasted of blood.”

Gone to ground

In his struggle for survival, we are taken with this lone wolf into a more self-analytical narrative that is also highly observational. The novel’s pace never slackens as he makes his way home, yet it becomes clear the foreign agents’ reach extends to England. He finally goes to ground in Dorset, an area that Household knew well. The idea for the book came to him while walking there and it becomes the battleground between the hunters and the hunted. As the protagonist burrows down into a hidden lane, further memories emerge to enrich this tense and grueling story.

When I read Rogue Male, I was on a walking holiday so I could easily visualise Household’s portrayal of the undergrowth, which becomes the character’s hiding place. In the book, our hero has the English landscape as his accomplice and he even makes friends with a recalcitrant tomcat he names Asmodeus. But his hideout is also a forbidding fortress. Household describes the concealed lane where ‘nettles grow as high as a man’s shoulder’ and the ‘fifty feet of solid blackness’ at night. It could end up as his hero’s grave.

The story of this concealment deep in England has even inspired the nature writer Robert Macfarlane, who attempted to locate the hidden lane with a friend and later wrote a lyrical book, Holloway, about the experience. It was also where Household’s son scattered the author’s ashes.

An obituary in the New York Times said that Geoffrey Household (pictured) developed the suspense story into an art form. He wrote many more thrillers, though it is the classic novel Rogue Male that will still be gripping readers in 75 years’ time. They really don’t make them like this any more.