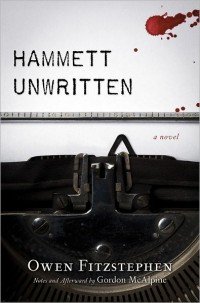

Owen Fitzstephen is the pen name of Gordon McAlpine. He’s dabbled in both ficiton and non-fiction in the past, with a book about baseball and novels touching on different genres. However his upcoming release Hammet Unwritten might really make his name here in crime fiction. It’s an interesting concept. It begins with the notion that he’s found a document by Hammett which suggests that the story behind The Maltese Falcon actually took place. And in Fitzstephen’s piece, Hammett himself is a central figure, having come into possession of the infamous statuette. The book isn’t out until February, but we decided to find out more about the book, and its author…

Owen Fitzstephen is the pen name of Gordon McAlpine. He’s dabbled in both ficiton and non-fiction in the past, with a book about baseball and novels touching on different genres. However his upcoming release Hammet Unwritten might really make his name here in crime fiction. It’s an interesting concept. It begins with the notion that he’s found a document by Hammett which suggests that the story behind The Maltese Falcon actually took place. And in Fitzstephen’s piece, Hammett himself is a central figure, having come into possession of the infamous statuette. The book isn’t out until February, but we decided to find out more about the book, and its author…

What inspired you to write about Hammett and reinvent the Maltese Falcon in this unique way?

I have always been intrigued by the seams where fact meets myth and, even more, by the dynamic exchange between the two. That Dashiell Hammett actually worked in his early 20s as a private detective presents obvious opportunities for such exploration. However, it was not until I came upon the following Hammett quote in a 1934 edition of the New York Evening Journal that I conceived a truly original way into his story: “All of my characters are real. They are based directly on people I knew, or came across.”

This put me in mind of his classic novel The Maltese Falcon, which I admire not only for its craft but also for the audacious revelation at its conclusion that the sought after black bird was still out there. I wondered who had been the real life models for the Fat Man, Joel Cairo and Brigid O’Shaughnessy? All of them must have known Samuel Dashiell Hammett in his PI days. And, if they were real, might the young Hammett have actually worked a case involving a black statuette, the mysterious nature of which exceeded even the fictionalised jeweled version in his famous novel? And, finally, might that real statuette have haunted Dashiell Hammett in unexpected ways long after he achieved fame and fortune? Good questions. So I wrote Hammett Unwritten to find the answers.

Do you prefer classic or contemporary mystery?

I draw inspiration from all manner of mysteries. Harkening back to a youthful affinity for Sherlock Holmes, I have recently happened upon the early 20th century novels of Maurice Leblanc, whose masterful gentleman thief Arsene Lupin engages in plot machinations that are as exhilarating as they are outrageous. While the Leblanc novels are dated in both style and content, they nonetheless still entertain. With Hammett’s subsequent emergence in the late 1920s, featuring grittier depictions of crime and far more nuanced characterisation, the genre truly grew up and, as such, the hardboiled appeals to the more sophisticated, adult reader in me.

Post-Hammett, I appreciate the rich combination of grit and compassion found in the mysteries of Georges Simenon, whose prolific production ought not to overshadow his greater achievement of having created one of the most appealing series detectives ever, Jules Maigret. When I feel the need to escape the familiar and be transported in time and place, the Judge Dee novels by Robert van Gulik never fail to satisfy. Among contemporaries, I appreciate the hard driving minimalism of James Sallis and Ken Bruen, the steamy richness of the Havana series by Leonardo Padura, and the wry, social criticism of mystery novels like Robert Ward’s Four Kinds of Rain.

Do you plan on writing more novels about Dashiell Hammett?

Do you plan on writing more novels about Dashiell Hammett?

I remain intrigued and inspired by Hammett. This has much to do with the contradictory elements of his life. Three examples – first, as a young man he worked as a violent strike-breaker for the Pinkertons, whereas in middle-age he worked as an organiser for elements of the American Communist Party, imprisoned for standing up to the red-baiting of Joseph McCarthy. Second, he wrote five classic mystery novels in a span of five years and then suffered a crippling writer’s block for the remaining 28 years of his life. Third, he was a faithless and notorious womaniser who nonetheless maintained a three decades-long relationship with one of the brightest women of his generation. I am reminded of a line in Shakespeare: “He was a man, take him for all in all, I shall not look upon his like again.” I have no particulars yet for another Hammett novel, but given time…

So, I guess the answer to your question is yes.

You’ve written novels on varied subjects. So far, do you have a favorite?

Hammett Unwritten is my favorite as it has afforded me the truest opportunity to explore the seams between reality and myth, as alluded to above. Also, the life of Dashiell Hammett provided not only great material but also some sense of Hammett himself, the author, whose imagined presence served me as a kind of writer’s whispering conscience, continually keeping me on the straight and narrow (but never too straight and narrow…)

You also have The Tell-Tale Start on the way, a novel for children. Do you find it difficult to transition writing for adults, then writing for the younger set?

The voice is different, naturally. But that is also often true when transitioning from one adult novel to the next. The complexity of plot and depth of characterisation differs as well. Nonetheless, I find that writing for two distinct audiences still draws from what is essentially the same source – a fierce drive to find the one true way of relating the story. Still, I don’t work on more than one book at a time.

I began writing The Tell-Tale Start while taking a break between drafts of Hammett Unwritten. The fictionalised Hammett and his cohorts had worn me to a brittle and confused state and so I turned to writing for kids to blow off steam by indulging in the truly preposterous. It worked. When I returned to Hammett Unwritten, I did so with a fresh eye and renewed energy. And, as a bonus, I sold The Tell-Tale Start to Viking as the first in a trilogy, to be published in 2013, 2014, and 2015.