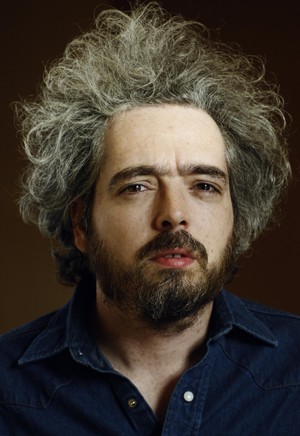

Stav Sherez is the author of three subtle and complex crime novels. His latest, A Dark Redemption, explores the repercussions of warfare back in their homeland for London’s Ugandan disapora. It’s an intense read, and this is brought about by Sherez’s highly accomplished prose, which promises great things for the next installment of the series. Today he joins us today to discuss his work…

Stav Sherez is the author of three subtle and complex crime novels. His latest, A Dark Redemption, explores the repercussions of warfare back in their homeland for London’s Ugandan disapora. It’s an intense read, and this is brought about by Sherez’s highly accomplished prose, which promises great things for the next installment of the series. Today he joins us today to discuss his work…

Can you tell us a little about A Dark Redemption?

A Dark Redemption is a psychological police procedural set in contemporary London. DI Jack Carrigan is called to investigate the murder of a Ugandan student found dead in her Bayswater flat. He thinks it’s the work of a serial killer but his partner, Geneva Miller, believes that the girl’s murder relates to her work on African politics. Carrigan’s not sure he can trust Miller. He doesn’t know she’s been seconded to his team to spy on him. On another level the book is about friendship and circumstance. About how our lives can suddenly hiccup and send us down unexpected tracks. It’s also about modern-day Africa and the countless small wars and ethnic bloodstorms raging through that continent. And it’s about survivor guilt and the things we do to make up for it.

What initially drew you to the political situation in Uganda?

I’ve been fascinated by African politics for several years and the more I read about Uganda and Joseph Kony the more I knew I would have to write about it. Kony is an incredible figure – a mad-eyed cult leader, wannabe mystic and rapacious marauder. He’s steeped the region in blood and chaos for over 20 years. And I kept coming back to the children, the kids Kony abducted and turned into soldiers for his militia, the Lord’s Resistance Army. I couldn’t imagine that kind of life, being ripped from your childhood and plunged into the furnace of war. How you would come back from that, and if you did…

London is vividly rendered in A Dark Redemption, was it important to you to show parts of the city and communities which readers may have not seen before?

It was very important to me. Having grown up in London, I’d stopped seeing it – it had become the wallpaper. That’s why the first two books were set abroad. Being in a foreign country forces you to see anew. But A Dark Redemption had to be set here so I needed to make London fresh to me, to see it with the eyes of a tourist, and the Ugandan illegal immigrant community allowed me to do that. It’s a part of London I was only vaguely aware of, and it was fascinating and intriguing. I was interested in how London, and all cities, are palimpsests where separate worlds exist side by side, in both space and time, mostly oblivious of each other, and the way a murder could chart the intersection of these worlds.

Religion is recurring theme in your work, what keeps drawing you back to the subject?

In The Black Monastery a priest says, ‘I believe mysteries are allegories for God. That it is in mystery and darkness wherein we find the light and not, as supposed, the other way around.’ I think there’s a definite connection between theology and detective work. Religious questions are questions of existence and ethics, about evil and how we deal with it, and these things have always interested me and are also at the core of the crime novel. Religion promises to bring meaning to the chaos of signs we call our lives and to make sense of the violence and suffering that are part of living. I’m agnostic but I’m drawn by what makes people believe, whether it’s in established religions or eerie-eyed cults. When belief waned in the 20th century we didn’t really stop believing in God – we only replaced one system with another, be it conspiracy theories, New Age, or the worship of stones.

After two standalone novels you’re now embarking on a series with Carrigan and Miller, how has this changed your approach?

It was only about halfway through the writing of A Dark Redemption that I began to think of this as a series. I realised there was more to the characters of Carrigan and Miller than I could possibly hope to put in one book, and once I knew I would continue with them a sudden freedom opened up. I no longer had to tie up all loose ends, I could leave things open and use the series to trace the arc of their lives over a period of years. And it lets me slowly simmer back-stories and sub-plots then bring them to the boil when they’re good and ready.

I know you’re a massive Jazz fan, do you find its styles and forms influence your writing?

It’s influenced me a lot. Or perhaps I was drawn to Jazz because it echoed the rhythms I always heard in my head. But, despite them being massively different forms, there are similarities. I never plot my books out beforehand and so the improvisational nature of writing is analogous to Jazz – you pick a standard theme, in this case the police procedural – and then start improvising different variations, finding your own space between the notes. And the plot itself often tumbles out like an improvised solo, though, of course, I do a lot of re-drafting later. But mainly, I think the influence is in the sentences, the way they pulse in and out, expand and contract and repeat to create a rhythmic substructure to underlie and propel the text.

So, what’s next for Carrigan and Miller?

A convent burning in a sleepy West London square. Ten dead nuns. An unaccounted for body. Misted history and thwarted rebellion. Squalid squats and towering tenements. London engulfed in a snowstorm. A case quickly spiralling out of control. Eleven days before Christmas.

Reading this at the moment. Really admire the thoughtful, elegiac tone that Sherez brings to an (often justifiably) maligned strata of the genre we all love. His hints about where the story’s going next have me ready and waiting for Book 2 already.

Plus the man knows his coffee and jazz. What more could one want?

Great job, Eva.