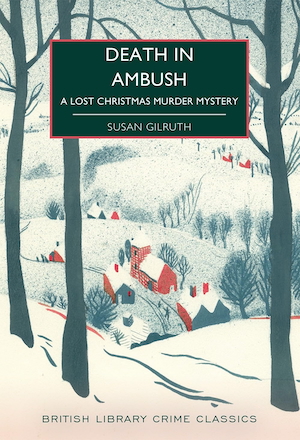

This year’s festive addition to the British Library Crime Classics series is Susan Gilruth’s Death in Ambush, which was first published in 1952. It is a Christmas-set mystery, yes, but one less about seasonal cheer and more about the tensions, hypocrisies and secrets that lie just beneath the surface of genteel society.

It is also notable for belonging to the period when the Golden Age of Detection was giving way to something more psychologically aware and socially grounded. Gilruth’s work echoes that of Margery Allingham and Cyril Hare, writers who understood that the real mystery of post-war Britain lay not in who committed crimes but in why ordinary people were driven to desperate acts.

In the bucolic village of Staple Green in Kent, Howard and Betty Sandys are beginning the build-up to Christmas. A houseguest, Liane ‘Lee’ Craufurd, arrives for what she anticipates will be several weeks of peace in the run-up to the festive season while her husband Bill is busy doing something secret for the War Office.

But the peace proves fragile. A glamorous widow moves to the village, lovers quarrel, neighbours gossip and old resentments fester. When Sir Henry Metcalfe, a former magistrate and keen collector of ceramics, dies unexpectedly after his wife is lured from the house by a hoax telephone call, the ‘holiday’ mood morphs into one of suspicion.

The discovery that Sir Henry’s death was due to murder transforms the villagers’ strange practices into potential motives. Lee is drawn into the investigation alongside old acquaintance Detective Inspector Hugh Gordon, who is dispatched from Scotland Yard to determine who among those with ill feeling towards Sir Henry cared enough to kill.

The mystery is built on social niceties, overheard conversations, subtle resentments and anxieties born of post-war austerity, change and tradition – material reminders that things have not yet returned to normal. These details are not simply window-dressing but give the plot impetus by influencing behaviour, breeding mistrust or feeding moral unease.

The world Gilruth depicts is one in transition, where pre-war gentility rubs awkwardly against post-war pragmatism. Electricity is coming to the village, servants are scarce and once-grand families have had to sell off land or heirlooms. Characters speak nostalgically of what has been lost, but their nostalgia often hides insecurity or envy.

Lee Craufurd, as the first-person narrator, strikes a nice balance by being both participant and observer. She is accepted as part of the social fabric – not a mere tourist – but also has sufficient remove to notice things that lifelong villagers take for granted or dismiss. She is curious and respectful without being cynical, providing insight into characters’ foibles.

Lee’s perspective reveals the way small clues accumulate: a strange call, how people avoid certain topics, the way no one seems exactly the same before and after an awkward cocktail party at the Sandys’ house. She is not a committed amateur sleuth, but her contributions in piecing together gossip, small contradictions and unexpected events are credible.

Hugh Gordon has a more traditional role, allowing him use of the formal investigative tools of the period, although he still plays catch up at times. Lee sometimes identifies – whether by chance or design – promising leads that Gordon must then officially follow. This mix of professional and amateur sensibilities works well, revealing both procedure and character.

Plotwise, Death in Ambush takes time to warm up, and the unravelling of the murder mystery is gradual. There is no immediate onslaught of bodies. Rather, there are tense moments, interpersonal friction and mysterious behaviour. After Sir Henry’s murder is made public, the questions mount: who had sufficient means, motive and hidden animus?

The atmosphere is one of cold country evenings and unspoken tension between public civility and private disquiet. Christmas is present, but more as a looming backdrop. There are decorations, seasonal fuss and family obligations, but the novel ends on 23 December, so much of the action takes place in the lead-up rather than during the holiday celebrations.

This works in the novel’s favour, heightening the sense of expectation, of tradition and ritual, which makes the subversion and discomfort caused by the murder feel sharper. It is less about the joy of the season and more about how heritage, memory and fear intersect, especially in people who have lived through war, loss, deprivation and social change.

The inherent repression is reflected in dialogue that often carries a double meaning – polite on the surface, cutting underneath. People who decline an invitation, who leave early, who answer awkwardly, all matter. There is wit in Lee’s observations on the habits of neighbours, the way people judge each other’s houses or guests and the absurdities of social norms.

At times, the story can verge on the cosy, but the undercurrent of unease is never far away. Some of the tension stems not from physical threat but from social pressure – what will people think, who will be embarrassed, what family reputations will be damaged. This is a crime novel as much about manners and community as about murder.

Staple Green is not a picturesque refuge – it is a community negotiating change. Beneath the veneer of neighbourliness, there is quiet resentment about class, gender and survival. The war is over, but its shadow lingers. Gilruth captures that mood of quiet uncertainty, of people trying to reassert old hierarchies even as those hierarchies begin to crumble.

The murder itself is symbolic: a rupture in the fragile order holding the village together. Sir Henry represents the older generation – privileged, self-assured, steeped in class entitlement – while the suspects include those on the margins: widows, dependents, professionals and outsiders. Each character’s motive is rooted in post-war disillusionment.

Gilruth’s portrayal of gender also deserves attention. The women in Death in Ambush play a spectrum of constrained roles – hostess, widow, dependent – but in those roles they display agency and complexity. Gilruth grants them interior lives that many Golden Age mysteries denied female characters.

The female perspective also sharpens the book’s social critique. It is women who sense the fragility of stability, who must navigate the small hypocrisies that men ignore or enforce. The murder investigation becomes not only a hunt for a killer but also an exposé of how women’s emotional labour holds the community together even as it suffocates them.

However, the inclusion of this social commentary does come at the cost of pace. The middle of the novel slows as Lee, Gordon and others collect clues, revisit conversations and consider motives. The absence of action and drama fits the crime but does cause a lag and a decline in tension. Still, the slow-burn logic eventually rewards patience with explanation.

Another issue is that some characters seem underdeveloped. There are plenty of village eccentrics, but some suspects’ motives are rather weak when compared with others, which can make their scenes feel a little perfunctory. But because the social milieu is so vividly realised, even these secondary figures contribute to the atmosphere.

Death in Ambush is a strong addition to the British Library Crime Classics lineup. It is both a vintage murder mystery and a character-driven whodunnit with social texture. Gilruth explores how darkness can lurk beneath even the most respectable surface and how nefarious deeds can be revealed by festive lights.

For more classic Christmassy crime stories, try Who Killed Father Christmas? and Other Seasonal Mysteries edited by Martin Edwards.

British Library Publishing

Print/Kindle

£2.99

CFL Rating: 4 Stars