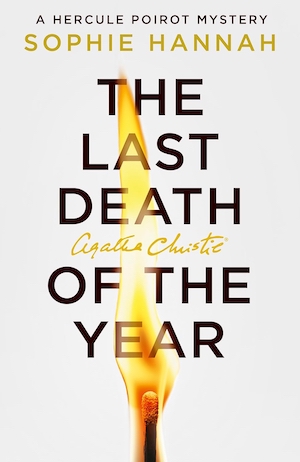

The New Year generally begins with fireworks rather than fatalities, but the stroke of midnight signals suspicion instead of celebration in Sophie Hannah’s The Last Death of the Year. The sixth novel chronicling the return of Hercule Poirot – which by necessity takes place before the exit of him in Agatha Christie’s Curtain – sees the sleuth enjoying another busman’s holiday.

New Year’s Eve, 1932. Poirot and Inspector Edward Catchpool arrive on the Greek island of Lamperos for what Poirot promises will be a relaxing holiday spent with very good friends. While it quickly becomes apparent that Poirot has never actually met their host, Nash Athanasiou, or any of the other guests – the aforementioned ‘Very Good Friends’ – staying at the House of Perpetual Welcome before, it’s clear that he has agreed to visit for a very particular purpose.

Of course, he won’t tell Catchpool what that purpose is. Where’s the fun in that?

As the downbeat detective attempts to figure out what’s going on, he’s reluctantly drawn into the festivities. Nash suggests that the group see in the New Year by playing a game he’s just devised: each guest must anonymously write a resolution for 1933, and then they will all attempt to guess which resolution belongs to which person.

The game proves to be about as entertaining as it sounds.

That is, until one of the anonymous resolutions proves to be a promise of murder. Could that be what Poirot has been waiting for? While most present dismiss the resolution as a joke in bad taste, Poirot seems to take the threat seriously, which prompts Catchpool to study his fellow guests more closely.

But how could ‘the last and first death of the year’ be accomplished? And when?

Agatha Christie loved island settings – Evil Under the Sun, And Then There Were None, A Caribbean Mystery – and cannily used them to juxtapose the opportunities for relaxation and ruthlessness. In taking up the mantle of Poirot, Sophie Hannah has proved adept at blending homage with innovation, and here she fosters another atmosphere of sunlit dread.

The Greek island setting offers the illusion of paradise: sparkling sea, warm air and welcoming terraces. Yet beneath the Mediterranean sun lies a current of unease. The House of Perpetual Welcome is both a sanctuary and a prison, a place where the ideology of forgiveness curdles into fanaticism.

The guests, who aren’t quite a cult but are well on the way to being one, notionally gathered in the spirit of goodwill and renewal, all carry old wounds that refuse to heal. As the clock ticks towards midnight, the game of New Year’s resolutions serves as a prelude to tragedy, a chilling reminder that what begins in jest can end in catastrophe.

This interplay between serenity and menace gives The Last Death of the Year much of its tension. Hannah’s command of atmosphere evokes the Golden Age of Detective Fiction, although her tone has a modern sensibility – quieter, more psychological and rich in irony. The closed circle setting, again beloved of Christie, enforces a feeling of confinement.

The island of Lamperos, isolated and self-contained, traps not only the suspects but also their ideals and hypocrisies. There is no escape, either physical or moral, from what unfolds. Hannah allows the dread to build slowly, letting the brightness of the setting amplify the darkness of the human motives.

Lamperos, beautiful yet cut off from the world, also mirrors the fragile nature of the guests’ relationships. What was meant to be a harmonious collective turns inward, revealing rivalries and moral fractures. In such an environment, the qualities that bind people together – faith, trust, the desire to belong – make them vulnerable to manipulation.

Hannah also channels the moralising of the Golden Age, albeit in more depth, incorporating an exploration of forgiveness into the mystery. The guests at the House of Perpetual Welcome live by a creed of unconditional absolution – every mistake forgiven, every past sin washed away. On the surface, this is an admirable philosophy.

Yet Hannah exposes the fragility and danger of such an idea when it is detached from moral accountability. Forgiveness becomes a form of denial, while compassion mutates into complicity. Poirot has to question what happens when forgiveness is granted without repentance. The answer, sadly, is chaos and corruption.

Forgiveness is not always what it seems, and the idea of appearance versus reality underpins the mystery. The house, the guests and the New Year party are façades concealing something darker. The ritual of resolutions – a symbol of fresh beginnings – morphs into an instrument of menace through the chilling promise of death.

Hannah uses this moment to consider the human need for reinvention and how easily that need can be perverted. The idea that good intentions can mask malice runs through The Last Death of the Year, and Poirot’s role is not simply to identify a murderer but also to expose layers of deceit and self-deception.

While she honours Christie’s signature structure – the gathering of clues, the assembling of suspects, the final denouement – Hannah’s approach to characterisation is more introspective. Poirot remains recognisably himself: dignified, meticulous, occasionally pompous but never unkind. Catchpool continues to provide a humane counterpoint to his cerebral detachment.

Together they examine statements, probe motives, revisit the characters’ backgrounds and sift through red herrings. The solution, when it comes, is typical of Christie: surprising but logically consistent, with enough retrospective clarity to make earlier misdirections feel fair rather than arbitrary.

But the suspects are more emotionally layered than the archetypal characters of Golden Age mysteries. They are neurotic, self-justifying and sometimes painfully modern in their psychology. This depth adds richness, as Hannah lingers on motivations and moral quandaries rather than propelling Poirot towards a solution.

In this way, Hannah extends the Christie tradition into new emotional territory. The Greek island, the New Year’s revelry and the fatal resolution all combine to show that, even in times of celebration, the shadows of the past persist. As Poirot might advise, never relax at a party where everyone insists they have nothing to hide.

For more modern interpretations of Agatha Christie, try Hercule Poirot’s Silent Night and Marple: Twelve New Stories.

HarperCollins

Print/Kindle/iBook

£12.99

CFL Rating: 5 Stars