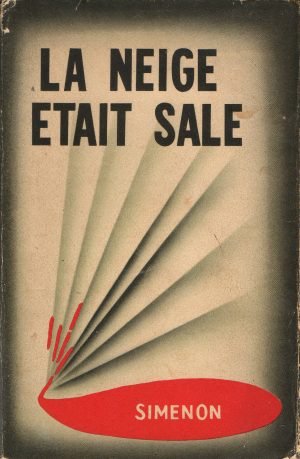

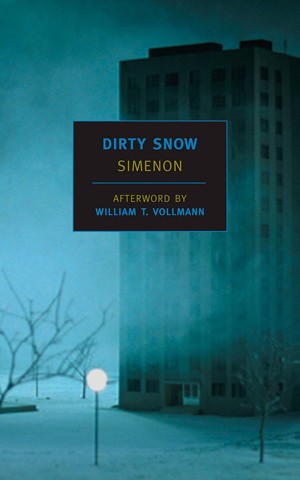

If you’ve read Georges Simenon’s classic of existential noir Dirty Snow you will probably believe there was mutual influence between Simenon and his contemporary Albert Camus. Dirty Snow certainly belongs on the same shelf as Camus’ The Stranger. The influence of Dirty Snow’s existential musings is still prevalent today in crime fiction across all borders, with critics citing authors from Jim Thompson to Patricia Highsmith. One notable characteristic of Dirty Snow that makes it distinct still is how it achieves its effect without resorting to graphic violence, as the cold-blooded killing happens mostly off-screen.

If you’ve read Georges Simenon’s classic of existential noir Dirty Snow you will probably believe there was mutual influence between Simenon and his contemporary Albert Camus. Dirty Snow certainly belongs on the same shelf as Camus’ The Stranger. The influence of Dirty Snow’s existential musings is still prevalent today in crime fiction across all borders, with critics citing authors from Jim Thompson to Patricia Highsmith. One notable characteristic of Dirty Snow that makes it distinct still is how it achieves its effect without resorting to graphic violence, as the cold-blooded killing happens mostly off-screen.

You may recognise traces of Dirty Snow in noir cinema as well, such as Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960) or George Sluizer’s The Vanishing (1988), where the serial killer is seen rooting around in the void for the most terrible ways victims can face their own death. 60 years after it was written, with its matter-of-fact ramblings of the fastidious sociopath Frank Friedmaier, Simenon’s novel is just as shocking today for its horrible banality.

For Simenon, Dirty Snow represents an alternative genre he called romans durs. These hard novels are characterised by a bleak and grim fatalism, where human souls hurl themselves pell-mell towards unknown limits regardless of the consequence. This is the very stuff of noir which plumbs deep into the darkness of the soul. Dirty Snow feels like a blend of Dostoyevsky and Jim Thompson, and hard it is.

During WWII, in a small, nondescript occupied town, a bored 19-year-old wannabe criminal named Frank Friedmaier decides to commit murder during the gloomy hours of curfew. Although his motives seem vague and fluid, the main draw of murder for Frank is the thrill of the first kill and the chance to impress the local criminals he admires, Kromer and Timo. Both notions are irresistible to the morally bankrupt youngster, who has the resolve of Dostoyevsky’s Raskolnikov but with none of the regret, and it’s through his cold and implacable viewpoint that we see events unfold.

During WWII, in a small, nondescript occupied town, a bored 19-year-old wannabe criminal named Frank Friedmaier decides to commit murder during the gloomy hours of curfew. Although his motives seem vague and fluid, the main draw of murder for Frank is the thrill of the first kill and the chance to impress the local criminals he admires, Kromer and Timo. Both notions are irresistible to the morally bankrupt youngster, who has the resolve of Dostoyevsky’s Raskolnikov but with none of the regret, and it’s through his cold and implacable viewpoint that we see events unfold.

Frank carries out a hastily contrived plot to kill an officer in the occupying force, but in utterly strange fashion, he deliberately allows his neighbour Holst, a streetcar conductor whose daughter has a crush on him, to witness the murder. With a borrowed knife which he promises to return to the lender with the corpse’s gun as a bonus, he kills the officer and then goes home to sleep.

So opens this ground-breaking noir by the prolific Simenon, mostly known for his Inspector Maigret series of policier novels. Simenon penned Dirty Snow in 1948 during the early part of his 10-year self-exile in the US after fleeing post-War Europe. During this period he had already written over 20 Maigret books, but Dirty Snow represents a much darker tendency. His romans durs are very distinct from the charming quaintness of the Maigret mysteries.

The country we’re in is never named, but Simenon’s anti-hero careens recklessly into the structures of authority, flashing his money and the green card that gives him freedom of movement. One audacious act after another shows him daring anyone to stop him. When he encounters affection, he sees it as weakness and will destroy anything that resembles it, as we see in the cold and callous murder that follows.

All this takes place in a small town where a precarious relationship exists between occupying forces and the locals that serve them, including the whorehouse Frank’s mother runs. The bordello may be the only place where food, gas, and coal are not rationed and Frank and his mother are hated by most everyone.

Georges Simenon had a pipe for each day of the year.

Simenon portrays excruciatingly well the abject poverty, hunger and desperation faced by the victims of war. He realistically describes the occupied towns’ inhabitants as they mill around the ration lines, their vacant expressions hollowed by despair. One thing the locals and the occupying forces have in common, however, is the abject fear of betrayal. On a dime, anyone can be an object of suspicion: one day you’re up, the next you’re down, executed as an enemy of the state.

Frank, however, feels untouchable. Pampered and privileged, he sulks about the town recruiting country girls into prostitution and obsessing over how his protected life has kept him from peering into the edges of destiny. He harps on the day when he was a kid, prevented from seeing what fate had in store for a kitten stuck in a tree.

Since the murder of the officer Frank seeks out the witness Holst, who exhibits no signs of snitching on him or even awareness of Frank at all. Failing to confront Holst, he only encounters his daughter Sissy. She disappoints him easily, and his attraction to the young innocent turns to disdain in a heartbeat. He turns her over to Kromer to be raped. His betrayal of Sissy is a turning point, and in the aftermath, he becomes even more obsessed with confronting her father Holst.

Frank is just asking for it, and even the protection of his mother, the local constable, and his connections in the underworld are not able to reign in his self-destructive compulsions. The final section of the book deals with Frank’s arrest, solitary confinement and the ordeal of his interrogation before his final sentence. To the end, Frank is ever seeking the boss of the boss so that he can stare him down.

Dirty Snow holds a mirror to the human condition, and in its final pages, the grim realities of existence culminate in death. In the hollow echo that follows, there is no exit and there are no winners. So is there any redemption after all this gloom and doom? Hardly. Frank feverishly seeks face-time with Holst, who witnessed the murder, father of the rape victim Sissy, and the father Frank never had. Holst forgives Frank in prison, but no-one can release the doomed man from his human torment, any more than we can help poor Bartleby!

For more on Maigret, read CIS: Revisiting Maigret. Classics in September 2016 is sponsored by Bloomsbury Reader.