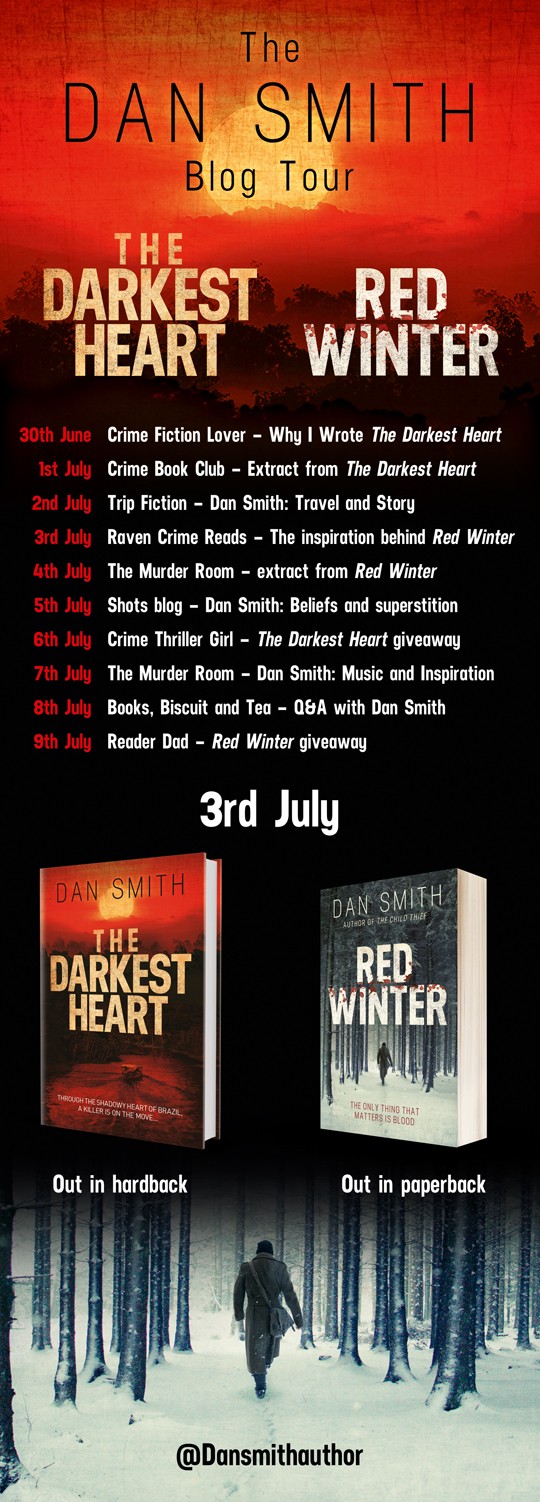

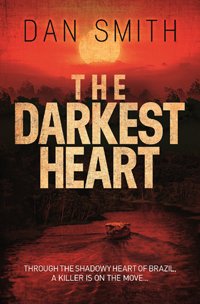

Images of Brazil and the beautiful game are all over our screens at the moment, so it’s a fitting time to see the country represented in crime fiction as well. After books set in very cold places – the Ukraine and Russia – British writer Dan Smith‘s next novel, The Darkest Heart, takes place in the sweltering jungle heat of Brazil, where blood runs as sure as the Amazon’s waters. Below the author talks about the inspiration behind his latest novel…

Images of Brazil and the beautiful game are all over our screens at the moment, so it’s a fitting time to see the country represented in crime fiction as well. After books set in very cold places – the Ukraine and Russia – British writer Dan Smith‘s next novel, The Darkest Heart, takes place in the sweltering jungle heat of Brazil, where blood runs as sure as the Amazon’s waters. Below the author talks about the inspiration behind his latest novel…

With the World Cup now in full swing, the media has overdosed on Brazil. Our screens and magazines have been filled with images of beautiful beaches, bronzed bodies, and flamboyant carnival costumes. Samba music fills the air and the party is on. We’ve also had a glimpse of the protests, the favelas, and the separation of rich and poor, but there’s a side to Brazil that the visiting football fans won’t see. Beyond Copacabana beach and football fever and endless parties – even beyond the hillside favelas – there’s a darkness in Brazil’s heart.

With the World Cup now in full swing, the media has overdosed on Brazil. Our screens and magazines have been filled with images of beautiful beaches, bronzed bodies, and flamboyant carnival costumes. Samba music fills the air and the party is on. We’ve also had a glimpse of the protests, the favelas, and the separation of rich and poor, but there’s a side to Brazil that the visiting football fans won’t see. Beyond Copacabana beach and football fever and endless parties – even beyond the hillside favelas – there’s a darkness in Brazil’s heart.

Let me tell you about the remote towns, a world away from the stadium cities of Rio, Manaus and Recife. Let me tell you about the vast waterways of the Araguaia and the twisting tributaries of the River of Deaths. Let me tell you about places where life is cheap.

Let me tell you about the Brazil I remember.

For four of my teenage years, Brazil was the country I called home. But this version of Brazil was a far cry from the lights and verve of Rio or the wealth and sophistication of Manaus; this was a rubber plantation 15 miles from a small frontier town, 500 miles from the nearest city. It was a place populated by drifters, criminals, and lost hopes who were all running from something and had come to the end of the line.

The vast and placid Araguaia river.

The murky waters

The landscape was huge. It was dominated by thick and impenetrable rainforest, punctuated by seas of cleared grazing lands, and right through it, ran the murky waters of the Araguaia river. Vast and uncompromising, the river was a wonderland of adventure, and as fishing and hunting were the only things for a young teenager to do in so remote an area, I became well acquainted with the Araguaia. Before long, my brother and I would spend days on its waters or camping on its sandy banks. I have vivid memories of the smells and sounds of those moments, and if I close my eyes now, I can feel the sun on my skin and smell the breeze on the water. Those are the feelings I tried to work into The Darkest Heart – to give the reader a strong sense of what it was like to be in such a huge and isolated place. And that sense of place, whether it’s Brazil, or Ukraine, or Russia, is a hugely important aspect of my writing. If I manage to transport my readers somewhere else, give them a flavour of it, then at least part of my job is done. The trick, I suppose is in choosing the right words and in knowing when to stop. I have to be sure I’m not indulging myself at the expense of tiring the reader when I describe the advance of a rainstorm, the isolation on the open waters, or the claustrophobia of the River of Deaths.

What is place, though, without character? Many of the people I mixed with in Brazil were uneducated and deeply superstitious. They warned my brother and me about going out onto the Araguaia alone, recounting stories of headhunters and monsters that lurked in the river and the forest. Yet the truth was that the workers were far more dangerous. Everyone was armed, and fiery Latin temperaments meant that violence was often used to resolve disputes – especially when alcohol was involved. It wasn’t unusual for guns to be drawn over a bottle of rum, or a card game.

A killer, maybe, for a few dollars?

For a few dollars…

But violence served other purposes, too. The electrician who wired our house was always smiling. He liked to tell a joke and have a drink, but he was also capable of the most terrible things. He killed people for money. For a few dollars he would cut a man’s throat or shoot him in the back, and discard of his body in the rainforest. And when he left the plantation to work elsewhere, he went to a town 30 miles away and resolved a problem the townspeople were having with a protection racketeer, by beating him up and cutting out his tongue. For that, he became a hero.

The man who tended the vegetable patch behind our house was reputed to have killed 17 men, but to me he was just a friendly old guy who touched the brim of his hat and said good morning. I never felt in danger. I never felt threatened even though I was surrounded by armed killers, and that is a juxtaposition that I have considered many, many times. In my writing I often explore and try to understand this sense that these good people could do such terrible things. Zico, the main character in The Darkest Heart, has many traits drawn from the people I met during my time in Brazil, but it’s this aspect that fascinates me the most.

In so much crime fiction we see calculating murderers, deranged individuals, twisted minds, but the people I knew were not like that. Zico, is not like that. He knows that what he does is wrong, but he is simply able to switch off. He is a killer, but he is not evil. He is not bad. This made him a difficult character to write, but it makes him more interesting – flawed characters are often the most engaging, but finding the balance can be tricky for a writer; encouraging the reader to sympathise with the character despite what they have done or believe.

The road to where Dan Smith lived in Brazil.

Our lady and the loggers

Place and character are not enough, though, and some would argue that story is king. In my writing, it is usually the characters who drive the plot, rather than the other way around, but the seed for the story has to start somewhere. In the case of The Darkest Heart, that seed came from an article I read about the murder of Sister Dorothy Stang.

Sister Dorothy Stang was an American born, naturalised Brasilian who was a member of the Congregation of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur. She was an outspoken campaigner on behalf of the poor and the environment and, in being so, was a thorn in the side of loggers and landowners. In 2005, on the way to a community meeting in Anapu, Sister Dorothy was confronted by two men who shot her six times. She was, of course, unarmed. In the article I read at the time, it was suggested that Sister Dorothy’s killers received the handsome sum of $40 for her murder.

$40 for a life.

The story stayed with me for a long time, and it made me rethink my opinions of the people I used to know when I lived in Brasil. The friendly electrician who wired our house would have probably done the same thing for $40. Perhaps our gardener might have done it too.

So I created Zico. I gave him some of the qualities of the people I knew, and I gave him a past. Then I put an offer on the table – money in exchange for life – to see exactly how far he would go. In following Zico’s journey along the river, though, I was reminded not just of the isolation and the danger of the environment, but also of its enormous beauty. I was reminded not just of the violence and the cheapness of life but of the incredible experiences I had, and of the warm and generous people I met.

Brazil really is a wonderful country filled with amazing people, and it’s a very special place to me, but it isn’t just samba and carnival and football. Brazil is bigger and better and far more extraordinary than all of those things. And while it has a darkness lurking somewhere in its heart, it also has a huge capacity for… well, the only word I can use is ‘life’.

The dark heart of Brazil is the first article in a blog tour for The Darkest Heart arranged by Orion. To read the second article click here. You can buy The Darkest Heart on Amazon here.