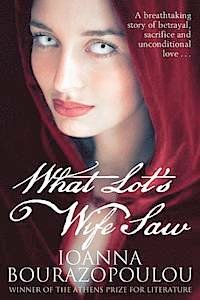

Compared to the Scandinavians and the French, Greek crime fiction authors seem few and far between. However Ioanna Bourazopoulou is a Greek author who has seen her novel What Lot’s Wife Saw translated into English. Set in a future when large parts of Europe are submerged due to the melting of the polar ice caps, the continents cities and demographics have changed radically. With large parts of the population addicted to a strange violet salt, the unpopular governor of this future society is murdered. Puzzle solver Phileas Book is called in to find out why. It’s acomplicated and staggeringly ambitious book bringing together crime fiction and sci-fi to some acclaim. In Greek, it won the Athens Prize for Fiction back in 2008. We invited Ioanna Bourazopoulou to join us here during New Talent November, welcoming the Greek author to appear here on Crime Fiction Lover…

In a nutshell, what is What Lot’s Wife Saw all about?

It’s a mystery novel. Nothing is quite what is seems. Though not lacking in traditional crime fiction elements – there is a mysterious death, six guilty-as-hell suspects, an eccentric puzzle-solver – there are certain peculiarities within these elements that differentiate the book from the classic crime fiction. Throughout the course of the narrative, the reader gradually realises that what needs to be discovered is not the culprit of the crime, but rather the crime itself. Although the setting is quite typical at first glance – we have a dead body, a group of suspects and any number of theories about motive – the reader can’t help but feel that there is another crime that has taken place here, other than the obvious one. A crime in which it is perhaps quite difficult to distinguish who is the victim and who is the culprit.

Are you worried that your richly layered, genre-busting writing might make it difficult for you to find an audience among traditional crime fiction readers or science fiction readers?

A bit – at least among those who prefer to know exactly what the deal is before submitting to a novel. I must admit this book doesn’t provide this sense of security: the floor can move suddenly under the characters’ (and readers’) feet, walls can turn into smoke and the premise changes constantly as the plot unfolds, and new, more pressing questions emerge. The reader has to be adventurous and patient at the same time. Which is a lot to ask, I know.

You came to novel-writing a bit later on in your career. Can you tell us what drove you to writing?

When I was younger and passionate about amateur drama, I felt safer using other people’s words and trusted non-verbal communication better. As my respect for language grew stronger, I started writing plays and then moved from writing plays to writing novels by the time I was 30. Words are my whole existence now. I think, feel and breathe through them, although they still deceive and terrify me. I harbour this secret fear that they have the power to change meaning without warning, sometimes in the middle of a sentence.

Playwriting was a useful preparation, an exercise in human reactions, direct speech and character development. The influence of the stage goes much deeper than that. I feel I owe theatre my fascination for magic, for exaggeration, for the surreal and the impossible. I seem unable to write a simple, everyday life story and I find it rather difficult to read one, too.

What kind of books/genres do you enjoy reading, and which writers have influenced you the most?

I don’t think I have a preferred genre. I love originality, surprises, mysteries and humour. I adore strange settings, complicated plots and unusual characters. I don’t mind bending the rules of literature, if it is done with finesse and I am ready to believe in miracles. My favourite authors include Lewis Caroll, Eugène Ionesco, Samuel Becket, Franz Kafka, Luis Borges, Zan Zene, Patrick Süskind, Margarita Karapanou, Thomas Mann, Carlos Somotha and so many more.

Your book has been very well received in Greece and has won a prestigious literary prize – congratulations! Do you think that there is a growing appetite for this kind of dystopian, rather dark landscape now in Greek fiction?

Markaris and Gakas are writers of noir literature, a genre that has become increasingly popular in the last few years and has given us many promising new authors, like Vassilis Danellis. Greek noir is closer to French noir, providing, apart from dark atmosphere and underground characters, a social analysis on crime and punishment, constantly exploring the relationship between corruption, power and want/need. Political and socioeconomic changes are inevitably reflected in Greek literature and the darker the times, the darker the books.