“When people ask me if I went to film school I tell them, ‘No, I went to films’,” said Quentin Tarantino. The director has an encyclopaedic knowledge of film and pop-culture thanks to his days working at the video rental store Video Archives in California, but his early work also drew significantly on the writing of crime authors like Elmore Leonard and Jim Thompson.

“When people ask me if I went to film school I tell them, ‘No, I went to films’,” said Quentin Tarantino. The director has an encyclopaedic knowledge of film and pop-culture thanks to his days working at the video rental store Video Archives in California, but his early work also drew significantly on the writing of crime authors like Elmore Leonard and Jim Thompson.

Reservoir Dogs

Quentin Tarantino burst onto the scene in 1992 with Reservoir Dogs, a gritty heist movie where you never see the heist. It’s full of conversational yet stylish dialogue, murky low-life criminals and visceral violence. The writer/director himself has said the heist theme and noir tone of Reservoir Dogs was influenced by Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing.

“I didn’t go out of my way to do a rip-off of The Killing, but I did think of it as my ‘Killing’,” he said.

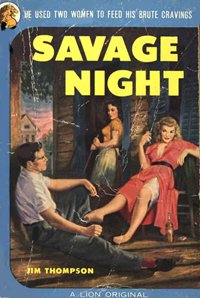

The 1956 film noir was written by Stanley Kubrick and Jim Thompson, based on Lionel White’s novel Clean Break. Yet in many ways Reservoir Dogs is a more faithful on-screen representation of Jim Thompson’s hardboiled crime fiction. Tarantino’s film is claustrophobic and raw, accentuated by the black and white colour palette, and reminiscent of Thompson’s bleak, nihilistic tone evident in the likes of Savage Night

The 1956 film noir was written by Stanley Kubrick and Jim Thompson, based on Lionel White’s novel Clean Break. Yet in many ways Reservoir Dogs is a more faithful on-screen representation of Jim Thompson’s hardboiled crime fiction. Tarantino’s film is claustrophobic and raw, accentuated by the black and white colour palette, and reminiscent of Thompson’s bleak, nihilistic tone evident in the likes of Savage Night and After Dark, My Sweet

.

Jim Thompson’s novels are devoid of heroes, instead full of grifters, losers, psychopaths and sociopaths. Similarly, Reservoir Dogs is bereft of any obvious good guys, even the undercover cop Detective Freddie Newandyke AKA Mr Orange (Tim Roth) is painted as a slimy, untrustworthy rat, rather than a courageous officer of the law. Similarly, in Thompson’s work, policemen were rarely depicted in a favourable light, from Pop 1280’s seemingly listless but in fact ruthlessly cunning sheriff Nick Corey, to the mentally unstable and horrifically violent sheriff Lou Ford in The Killer Inside Me – a character cut from the same dirty cloth as Michael Madsen’s blood-thirsty Mr Blonde.

Pulp Fiction

The 1994 Cannes Palmes d’Or winner is the epitome of 90s cinema and Hollywood crime. Pulp Fiction interconnects three stories of LA mobsters, hitmen and small-time criminals. Essentially, it’s like three short stories written by Elmore Leonard, realised on the big screen.

“Leonard opened my eyes to the dramatic possibilities of everyday speech,” said Tarantino.

The pop-culture infused, rhythmic dialogue of Pulp Fiction reflects the way Leonard’s own characters talk – sharp and smooth, peppered with street slang and cultural idiosyncrasies, but never too much, never getting in the way of the story. Hitmen Jules Winfield and Vincent Vega discussing what you call a Quarter Pounder with Cheese in Europe, is probably the most famous example, and has been aped millions of times since, always to lesser effect.

“I got the idea of doing something that novelists get a chance to do but filmmakers don’t: telling three separate stories, having characters float in and out with different weights depending on the story,” said the director (left).

“I got the idea of doing something that novelists get a chance to do but filmmakers don’t: telling three separate stories, having characters float in and out with different weights depending on the story,” said the director (left).

Largely revolving around the MacGuffin of Marcellus Wallace’s golden briefcase, the three storylines of Pulp Fiction take as much from Elmore Leonard’s storytelling style as they do from his gangster patois dialogue. Leonard loved setting up familiar genre stories that readers had seen hundreds of times before – the ex-con trying to go straight, bank robbers with a list of rules, the escaped convict falling for a police-woman – then he’d subvert them, and twist them in unexpected ways, often through accidents attributed to the characters being out of time, or out of place.

Tarantino does the same in the three tales of Pulp Fiction – Butch the boxer is supposed to throw his fight but doesn’t, Vincent Vega has to take his gangster boss’ wife out and show her a good time but not too good, and Jules Winfield; the hitman who finds God. Tarantino would complicate and resolve these established genre stories in surprising and extreme ways – Butch saving the gangster he’s in debt to from a couple of inbred hicks, Vincent Vega giving an adrenaline shot to the heart of an overdosing Mia Wallace, and Jules showing mercy to the small-time crooks Pumpkin and Honey Bunny (Tim Roth and Amanda Plummer) who try to rob him in a diner. What Tarantino clearly learnt from Leonard is that it’s fine for the premise of your genre stories to be clichéed, as long as where the characters take this premise is startlingly unique.

Jackie Brown

In 1997 Tarantino adapted Elmore Leonard’s Rum Punch into Jackie Brown

. Starring Pam Grier, the film was a fusion of crime caper and classic Blaxploitation, resulting in one of the best adaptations of Leonard’s material, which as cine-history has proved – despite its Hollywood-friendly style – isn’t the easiest to transfer to the big screen.

“Elmore Leonard was a real mentor to me as far as writing is concerned. He helped me find my voice,” said Tarantino.

Despite dropping a couple of secondary characters and building on several of the primary ones, not least Ordell, Tarantino’s film follows Leonard’s plotline faithfully. But it is in the dialogue of Jackie Brown’s script where Tarantino shadows Leonard’s low-life naturalism almost to the letter. As we’ve said, Tarantino’s dialogue was heavily inspired by Leonard’s but Tarantino typically took the realism that much further – frequently referencing pop-culture, whether it’s a breakfast cereal or a burger joint, using sometimes obscure street slang, and going off on tangents discussing the metaphorical meaning of Madonna’s song Like a Virgin . However in Jackie Brown he largely eschews that trend and as a result the film is an accurate and thoroughly successful adaptation, if a little muted compared to the rest of the distinctive director’s oeuvre. But perhaps for this very reason, it stands out, it shows some restraint. Like a typical Elmore Leonard protagonist it’s cool, calm and composed, and is arguably a more mature picture for it.

Despite dropping a couple of secondary characters and building on several of the primary ones, not least Ordell, Tarantino’s film follows Leonard’s plotline faithfully. But it is in the dialogue of Jackie Brown’s script where Tarantino shadows Leonard’s low-life naturalism almost to the letter. As we’ve said, Tarantino’s dialogue was heavily inspired by Leonard’s but Tarantino typically took the realism that much further – frequently referencing pop-culture, whether it’s a breakfast cereal or a burger joint, using sometimes obscure street slang, and going off on tangents discussing the metaphorical meaning of Madonna’s song Like a Virgin . However in Jackie Brown he largely eschews that trend and as a result the film is an accurate and thoroughly successful adaptation, if a little muted compared to the rest of the distinctive director’s oeuvre. But perhaps for this very reason, it stands out, it shows some restraint. Like a typical Elmore Leonard protagonist it’s cool, calm and composed, and is arguably a more mature picture for it.

Tarantino’s a magpie when it comes to sources of inspiration, and he’s never tried to hide it. But with Elmore Leonard’s style of storytelling, he was more than just inspiration to the director, the classic crime novelist really helped shape Tarantino’s voice.

With 2013’s Django Unchained and next year’s The Hateful Eight, Quentin Tarantino’s obviously on a roll with his Westerns, the genre Elmore Leonard actually started his career in, but it would be great to see the director returning to his crime roots and subverting some of those genre stories in raw and surprising ways. Like an adrenaline shot to the heart, perhaps crime on the big screen could do with a jolt.

Have a look at our top 20 classic crime movies here.