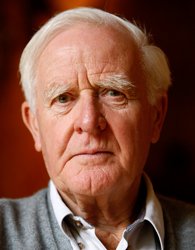

For 53 years, David Cornwell has been publishing under his pseudonym John le Carré. He originally adopted the name because he was writing about fictional spies while toiling in his day job for the British Intelligence Service. Such literary excursions probably wouldn’t be allowed today. But while he is known for superior, nuanced espionage thrillers, his early work has strong elements of the crime novel.

For 53 years, David Cornwell has been publishing under his pseudonym John le Carré. He originally adopted the name because he was writing about fictional spies while toiling in his day job for the British Intelligence Service. Such literary excursions probably wouldn’t be allowed today. But while he is known for superior, nuanced espionage thrillers, his early work has strong elements of the crime novel.

Le Carré’s second book, A Murder of Quality, was actually a mystery novel about a killing in a boarding school. It didn’t involve the shadowy espionage community to the same extent as the rest of his books. Perhaps that is why it’s a novel that le Carré has tended to disregard when it’s come up in interviews over the years. The cosy English murder has long since been expunged from his literary repertoire.

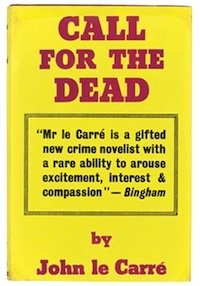

Call for the Dead, his 1961 debut, also begins as a crime novel. A Foreign Office official, Samuel Fennan, is found dead at home in Surrey, a suspected suicide following an investigation into his Communist past as an Oxford student. Case closed, as far as the senior intelligence officers are concerned. However, the investigating officer was George Smiley, who can’t quite accept this convenient solution. Following an anonymous tip-off, he had interviewed Fennan and liked him. The accusation was clearly not going to be pursued any further, so the supposed suicide troubles Smiley.

Cuckold and master spy

George Smiley is, of course, one of the most memorable fictional characters of the last 50 years, thanks in part to Sir Alec Guinness’s portrayal of the mole-like master spy in the British television adaptations of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy and Smiley’s People. Gary Oldman also earned plaudits for his portrayal of Smiley in the 2011 movie adaptation of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.

However, Smiley’s also a fully-formed character on the page. His first outing, in Call for the Dead, is a revealing introduction to a contemplative hero who went on to appear in seven further novels by le Carré. We learn that his wife, Lady Ann, has left him for a Cuban racing driver and Smiley takes some consolation in his counter-intelligence work and his love of Baroque German literature. This sensitivity to the poets was later employed by Colin Dexter in his creation of Morse; both of these academic investigators also display occasional, shocking flashes of anger that hint at their deeper passions.

Smiley served in Germany in the build-up to war, recruiting agents for the British, and this part of his life plays a key role in Call for the Dead. He continued this work in Sweden until recalled home in 1943 when it was clear his cover was blown. When we meet Smiley, he’s weary of the ‘brilliantly lit corridors, the smart young men’ and in middle-age has acquired the nickname Mole.

Nevertheless, he’s a tenacious investigator and he quickly alights on a key clue in the supposed suicide. Shortly before his death, Fennan had rung the telephone exchange to arrange a morning alarm call – hardly the action of a man intent on suicide. An undrunk cup of cocoa also makes Smiley suspicious, while Fennan’s wife, a concentration camp survivor, proves to be a troublesome interviewee.

Sherlock’s supporting role

Smiley is so angered by his bosses’ casual dismissal of the case, he quits the Service and investigates the death of Fennan himself. When he returns to his home in Chelsea and spots activity behind the windows, he realises – thanks to the quick instincts developed in an all-consuming career as a spy – that his life is in danger. Smiley immediately leaves and seeks out Surrey detective Inspector Mendel, who was investigating the death of Fennan as his final case before retirement, and gets a helping hand from fellow spy Peter Guillam. Even at his first attempt, le Carré has an obvious talent for the telling descriptive detail or piece of dialogue. Both Mendel and Guillam are well-drawn characters and they also appear in later books in the Smiley series. Sherlock star Benedict Cumberbatch played Guillam in the 2011 Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.

It’s also a miracle of concision that le Carré achieves so much back-story and drama in a novel of 150 pages. There is a case of Cold War espionage at the heart of the book and we learn about the tradecraft that agents employ in gathering intelligence. But you might well suspect that the Golden Age of detective fiction had its influence on le Carré for his debut set in London and Surrey. The plot involves secret meetings in a theatre, a car dealer in a dodgy pub, and obtuse policemen. For part of the book, Smiley cogitates on the case while incapacitated in hospital, an approach that Josephine Tey made so effective in The Daughter of Time a decade earlier.

Call for the Dead is, of course, a period piece. Modern readers may be baffled by the idea of ringing a telephone operator to arrange an alarm call. Yet it has action aplenty and stands up well to the modern thriller. It may be a constrained, crime-tinged novel that the author probably doesn’t consider representative of his body of work, but le Carré has an awful lot of fun with his characters as they track a spy ring across the familiar London streets and through leafy suburbia.

In his first outing, le Carré showed he was able to write sympathetically about divided loyalties in the midst of an ideological battle, and explore the ambivalence at the heart of a thoughtful spy hampered by his political masters. For that reason, le Carré’s literary career survived the end of the Cold War and his searching, provocative thrillers remain as relevant as ever.