We’ve just been celebrating the 123rd birthday of Agatha Christie, who created spinster sleuth Miss Marple in 1926. But if you thought Marple was the first female literary detective – albeit, an amateur – you might be surprised to learn you were out by several decades. Thanks to the British Library’s recent revival of lost Victorian suspense novels, devotees of classic crime can now encounter the first women detectives – and they’re available as ebooks.

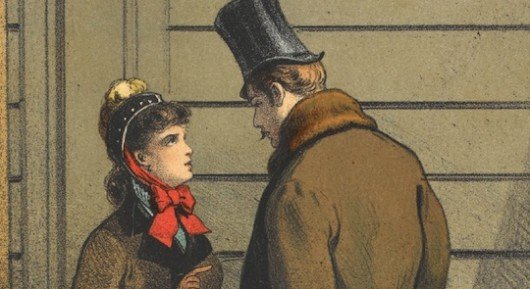

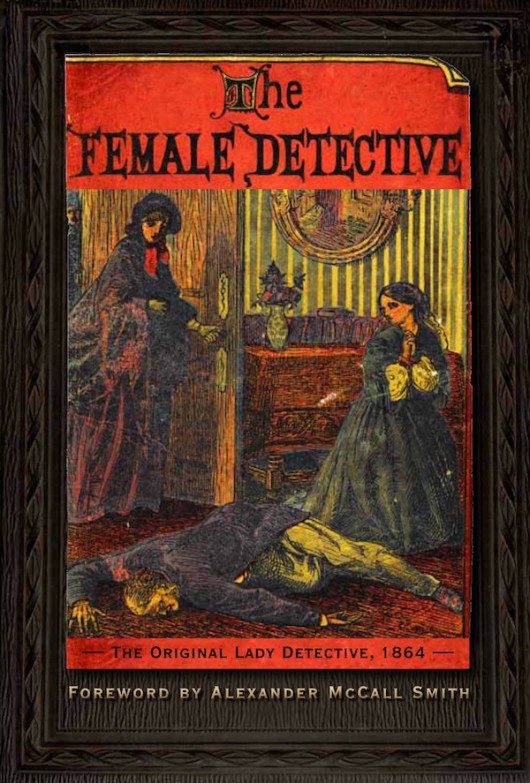

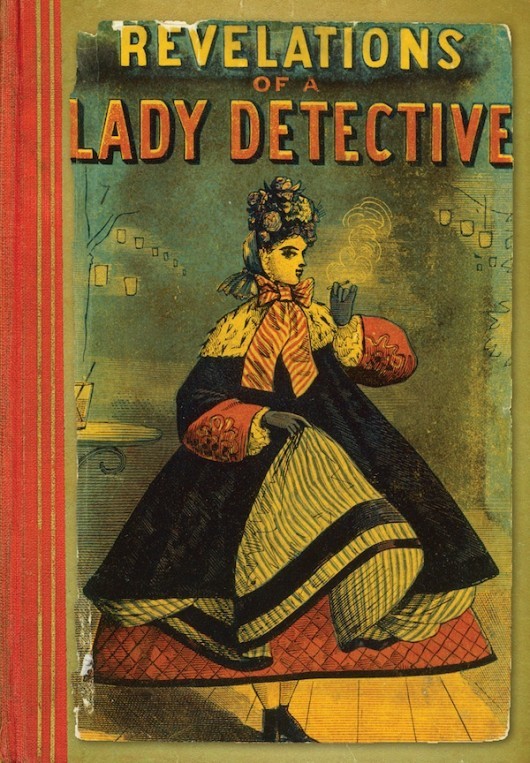

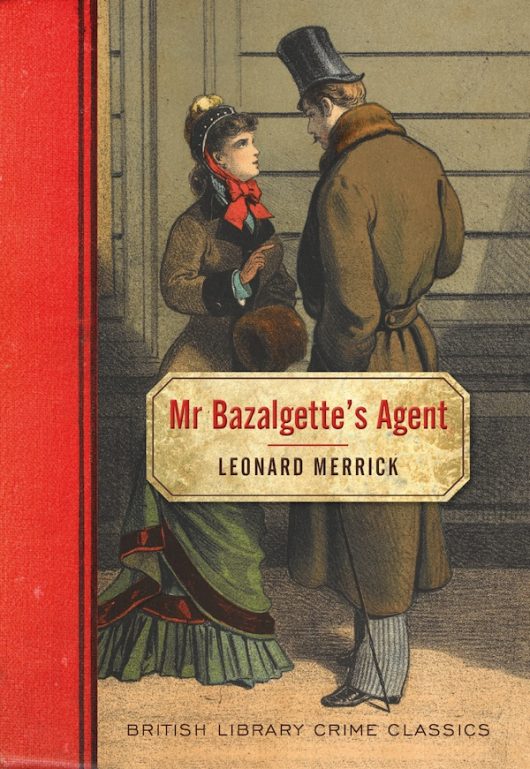

The Female Detective by Andrew Forrester was published in 1864 and its serial adventures feature Mrs Gladden, an undercover police agent – women were not formally recruited to London’s Metropolitan Police until 1923 – who employs subterfuge and logical deduction. Revelations of a Lady Detective by William Stephens Hayward followed a few months later and features the even racier Mrs Paschal, who smokes, carries a revolver and discards her crinoline to go down a sewer, but also shows the sort of clinical reasoning that Sherlock Holmes would display decades later. Mr Bazalgette’s Agent by Leonard Merrick appeared in 1888 and can claim to be the first British novel featuring a female detective rather than a collection of serial adventures.

With Mr Bazalgette’s Agent republished by the British Library this month, we quizzed Kathryn Johnson, curator of theatrical manuscripts and the excellent Murder in the Library exhibition earlier this year, and commissioning editor Lara Speicher about these pioneering women detectives.

With Mr Bazalgette’s Agent republished by the British Library this month, we quizzed Kathryn Johnson, curator of theatrical manuscripts and the excellent Murder in the Library exhibition earlier this year, and commissioning editor Lara Speicher about these pioneering women detectives.

Why did the British Library decide to republish these forgotten female detectives?

Female detectives have always been popular, from Miss Marple to Mma Ramotswe. The three first female detectives in British fiction were unavailable – except in a scholarly edition, for the first two – and we thought readers would be interested to read the books in which the tradition of female detectives started.

What does a woman detective bring to the story that a male character could not?

Mrs Gladden herself tells the reader that women will talk to another woman far more readily than they will to a man, and that she knows that within a few hours of striking up an acquaintanceship with a woman, she will be hearing all the useful local gossip. She also remarks elsewhere in the stories that as a woman she can so easily assume the role of a maidservant or governess, because as a servant she becomes almost invisible to the people she is investigating. She is also able to trade on the very widespread male assumption that a woman could not possibly have a head for business or indeed criminality.

Is it possible to make a connection between these characters and later female detectives such as Miss Marple and Alexander McCall Smith’s Precious Ramotswe?

Miss Marple and Mma Ramotswe are prime examples of women turning to good use the roles their essentially patriarchal society has attempted to slot them into. Both of them take the opportunity to listen and to observe and to be humanely curious, rather than rush into action. And Sue Grafton’s female detective Kinsey Millhone, who first appeared in 1982, is still using the habit of people to ignore or take no real notice of those they think have no relevance to them – she dresses in plain generic overalls and carries a clipboard, and householders just assume she is a meter reader sent by the oil or gas company, allowing her to get on with her real investigations unobserved.

Mr Bazalgette’s Agent was disowned by the author and almost impossible to get hold of until the British Library decided to republish it. Why did he abandon his literary creation?

Merrick said about the book: “It’s a terrible book. It’s the worst thing I ever wrote. I bought them all up and destroyed them. You can’t find any.” He went on to become a prolific author but he never wrote another detective novel. According to the scholar of crime fiction Mike Ashley, Merrick may have felt that his book owed too much to a book published in the USA in 1880, eight years before Mr Bazalgette’s Agent, a dime novel called The Lady Detective, by HP Halsey, although there is no way of proving this, or even whether Merrick read the American book.

There’s also debate over the authorship of Revelations of a Lady Detective – and is it fair to say that Hayward was familiar with criminal behaviour?

There’s also debate over the authorship of Revelations of a Lady Detective – and is it fair to say that Hayward was familiar with criminal behaviour?

According to Mike Ashley’s introduction to Revelations… Hayward came from a landed family but became a profligate youth. He gambled away his money on horses and was arrested twice, once on a charge of rape (the charge was dropped when the accuser did not come to court) and once as a debtor, but seems to have reformed when he married and set out to make a respectable career as an author. The other candidate for authorship, Bracebridge Hemyng, would have been acquainted with the law through his family background and his early career as a barrister, but a complex web of attributions of other novels makes it much more likely that Hayward was the author in question.

The Female Detective serial includes an account based on the notorious infant murder of Francis Saville Kent in 1860. Were true crime cases a key influence on these revived female detective books?

Not to any great extent. It would have been difficult for any writer of crime stories to avoid ‘The Road Murder’ as it was widely called at the time. Many articles and pamphlets on the case were published within months of the original legal proceedings, in an undignified scramble which still has the power to surprise a 21st century reader used to the excesses of modern tabloid journalism

Mr Bazalgette’s Agent is quite sophisticated rather than sensational in its diary-entry form. Given that it doesn’t feature a murder, how do you think it stands up today as a crime novel?

Rather well. The author put his own experience of South Africa to good use so that there is a real sense of place and the character of Miriam Lea is intriguing. Making Miss Lea an unsuccessful actress who has been making a respectable living as a governess until her employers discover her thespian past neatly gets the reader on the side of the central character and also links us to a more recognisable era. The general atmosphere of the novel is also a world away from the lurid melodrama of the penny dreadful era, and is a good pointer to the fact that the almost exclusive concern of the crime novel with murder did not come about until well into the 20th century.

Are these republished books and the Murder in the Library exhibition a recognition that crime fiction is of cultural and historical significance?

Are these republished books and the Murder in the Library exhibition a recognition that crime fiction is of cultural and historical significance?

A truly staggering proportion of fiction published across the world comes under the crime fiction label – possibly as much as one-third. To use one of the examples we showed in the exhibition, James Lee Burke’s The Tin Roof Blowdown, which is set against the tragic and horrific events surrounding Hurricane Katrina and the damage wrought in New Orleans and the surrounding district, has been described as possibly the best individual piece of writing on the event. People still read the puzzle-based mysteries of Agatha Christie with huge enjoyment, but there is so much more variety in theme and setting now available.

Do you have any further female detectives or vintage crime to be re-published?

Yes, we are planning many more in our British Library Crime Classics series. This November we are publishing a 1930s country house murder mystery, The Santa Klaus Murder. Next spring we are publishing four more crime novels from the 1930s, set in Cornwall, the Lake District, Oxford and on the London Underground.

Look out for a review of Mr Bazalgette’s Agent this month.