During New Talent November, we reviewed Gwen Parrott’s wonderful debut novel Dead White. It’s an interesting book for several reasons. Firstly, it was originally written in Welsh before being translated by the author herself for publication by Pageturners. Secondly, it’s set in the 1940s, two years after World War II. Below Gwen Parrott outlines why a 1940s setting is both easier and harder than you think…

During New Talent November, we reviewed Gwen Parrott’s wonderful debut novel Dead White. It’s an interesting book for several reasons. Firstly, it was originally written in Welsh before being translated by the author herself for publication by Pageturners. Secondly, it’s set in the 1940s, two years after World War II. Below Gwen Parrott outlines why a 1940s setting is both easier and harder than you think…

So, it’s over to the author, and you’ll also find a Welsh translation of this piece lower down…

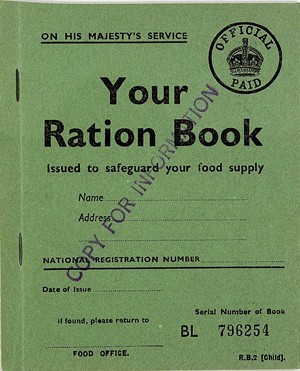

The 1940s? Are they really historical? This doubt must strike many crime novelists who consider setting a novel back in the 1940s. After all, so many people remember that period well. Their tales of the privations of rationing, travel restrictions and ‘make do and mend’ are very familiar. And quite apart from its familiarity, a 1940s setting can seem to be an easy option. It is such an intensely documented period that it is relatively easy to find out exactly what people were eating, how they were dressing, and to some extent, how they thought and acted. Their speech is even recorded on film and radio. And surely, the very lack of electronic devices and the isolation due to unsophisticated telecommunications makes it easier to fashion a murder story. Yet, when it actually comes down to writing about it, what at first sight seems so familiar can suddenly present all manner of stumbling blocks in portraying the nitty-gritty of daily life at the time.

The 1940s? Are they really historical? This doubt must strike many crime novelists who consider setting a novel back in the 1940s. After all, so many people remember that period well. Their tales of the privations of rationing, travel restrictions and ‘make do and mend’ are very familiar. And quite apart from its familiarity, a 1940s setting can seem to be an easy option. It is such an intensely documented period that it is relatively easy to find out exactly what people were eating, how they were dressing, and to some extent, how they thought and acted. Their speech is even recorded on film and radio. And surely, the very lack of electronic devices and the isolation due to unsophisticated telecommunications makes it easier to fashion a murder story. Yet, when it actually comes down to writing about it, what at first sight seems so familiar can suddenly present all manner of stumbling blocks in portraying the nitty-gritty of daily life at the time.

Rural North Pembrokeshire in Wales, the setting of my novel Dead White, presents several challenges from this point of view. In many ways, life there in the 1940s would have resembled life in the Edwardian era. Many remote communities had no electricity supply until the late 1950s, although urban communities had long been on the grid. Frankly, when something as essential to modern life as an electricity supply is missing, it can subtly undermine a writer’s best-laid plot. The need to think ahead vigilantly, to weigh plot options against criteria that are, by now, alien to us, is a distraction. Could this character have done that in the pitch black? What arrangements did people make for boiling a kettle quickly, or for keeping food fresh without a fridge? It may help to imagine oneself in a permanent power cut, but in actual fact, modern methods of coping are not those of the 1940s.

Throwback technologies

Throwback technologies

Writers need to be familiar with candlesticks and paraffin lamps, open coal fires and back boilers, and the utter necessity of a reliable torch. Many homes had no indoor bathroom and no piped water, either. Even the local school would have been reliant on open coal fires, and on the older pupils to stoke them. The fact that non-academic children in rural areas stayed at the local school until they were 14 is another feature of life that has disappeared from our consciousness. The intentions of the 1945 Education Act to provide universal secondary education were not realised in some places until the early 60s. Coupled with the restrictions of rationing, which stayed in force until 1953, it becomes evident that this was a different world.

Oddly, the fact that Dead White is set in the appalling winter of 1947 was helpful in that it intensified the difference and the isolation. Even the limited communication possibilities provided by the few houses that had a telephone and the public phone boxes would not have been viable. People were thrown back on the resources of an even earlier time, such as using a horse and cart to clear the road for the milk lorry. Co-operation, always a feature of rural Welsh life, became vital for survival.

Swansea, after the blitz. Devastation which resonated long after VE Day.

Sexual inequality

However, it’s strange to think that while the lack of amenities in the 1940s has receded into the mists, the gender inequalities still ring true. Possibly, in my case, this is due to family history. My grandmother, a rare female graduate since 1916, had to give up teaching as soon as she got married. It’s little wonder that it came naturally to make my protagonist, Della Arthur, very protective of her independence. Her status in the community, by virtue of her education and job, would bring its own responsibilities and restrictions. From the point of view of the story, this was a mixed blessing. There are places where Della cannot afford to be seen, like the local pub, the ‘Hut’. That isn’t very convenient when she’s on the trail of a murderer. Her behaviour is watched and measured against standards that now seem unreasonable, but were a reality of the time.

Having said that, it’s easy to forget that it’s not a one-way street. The 21st century is not more libertarian than the 1940s in every respect, because although Della would have been condemned for drinking alcohol, she would almost have been expected to smoke, as it was a social norm. From this point of view, one of the most useful resources for a true picture of how people behaved and thought in the 1940s are the series of books published from the Mass Observation diaries kept for many years by some 500 individuals. They are invaluable, as they explode myths and pieces of received wisdom such as our belief that anti-Semitism was only rampant among the Nazis. But taboos and preoccupations change, and being true to the time almost inevitably means making characters with whom writers wish readers to identify do and say things of which some modern readers will disapprove strongly. There is a tightrope to be walked between representing the period truthfully while not losing readers’ sympathy.

Chapel and pub

Socially, in those days, rural Wales revolved around the chapel and the pub. People belonged to one faction or the other, outwardly at least, but especially in isolated communities, one should not forget how powerful a force for intellectual and cultural betterment the chapels were. It is fashionable nowadays to decry them as being narrow and repressive, but they actually provided much-needed social contact, education, events and trips, not to mention an outlet for theological and philosophical debate. Even Della, from her equally religious urban background, is astonished at all the activity.

The importance of the chapels also extends to their being a stronghold of the Welsh language, improving and consolidating literacy. At this time the whole community would have been Welsh speaking. People from ‘away’, apart from prisoners of war, hadn’t started to arrive. Within their community, apart from on the radio, and in school, they would rarely have heard spoken English, although they would all have been bilingual. As Dead White was originally written in Welsh, where cultural resonance means that matters such as these are taken for granted, the question naturally arose as to how much exposition and explanation was required in the English version. The answer seemed to be the minimum, now that translated novels from all manner of languages have become common, trusting that the reader’s intelligence would supply the rest.

The importance of the chapels also extends to their being a stronghold of the Welsh language, improving and consolidating literacy. At this time the whole community would have been Welsh speaking. People from ‘away’, apart from prisoners of war, hadn’t started to arrive. Within their community, apart from on the radio, and in school, they would rarely have heard spoken English, although they would all have been bilingual. As Dead White was originally written in Welsh, where cultural resonance means that matters such as these are taken for granted, the question naturally arose as to how much exposition and explanation was required in the English version. The answer seemed to be the minimum, now that translated novels from all manner of languages have become common, trusting that the reader’s intelligence would supply the rest.

Doing research is easy for the 1940s. Deciding how much of it to stuff into a novel is the hard part. The point is that when people are living in a certain epoch they are not constantly discussing and dissecting it in every conversation. They are operating largely on shared, unspoken assumptions. You have to find a way of imparting information indirectly, almost as a throwaway line here and there, to give modern readers the sense of it without weighing the story down. It has to be a believable part of the action, as does any mention of current affairs.

And on top of all this comes thinking up a plot for a whodunnit!

Here is the story in Welsh – it’s the first bilingual article to appear on Crime Fiction Lover!

Y 1940au? A ellid dweud eu bod yn hanesyddol mewn gwirionedd? Mae’n rhaid bod yr amheuaeth ynghylch hyn yn taro llawer o awduron nofelau ditectif sy’n ystyried gosod nofel nôl yn y 1940au. Wedi’r cyfan, mae gan gymaint o bobl atgofion byw o’r cyfnod. Mae eu hanesion am galedi’r dogni, y cyfyngiadau ar deithio ac ‘ymdopi a thrwsio’ yn gyfarwydd iawn. Ac ar wahân i hynny, gall gosod nofel yn y 1940au edrych fel dewis hawdd. Dogfennwyd y cyfnod yn drylwyr ac mae’n gymharol hawdd i ganfod gwybodaeth am beth yn union roedd pobl yn ei fwyta, sut beth oedd eu gwisg ac i ryw raddau, sut roeddent yn meddwl ac yn ymddwyn. Recordiwyd eu lleisiau hyd yn oed ar ffilm ac ar y radio. Ac yn ddiau, mae absenoldeb dyfeisiau electronig a’r unigedd sy’n ganlyniad i delathrebion ansoffistigedig yn ei gwneud yn haws i lunio stori dditectif. Eto, wrth ysgrifennu, gall beth a ymddengys mor gyfarwydd gyflwyno pob math o feini tramgwydd annisgwyl wrth geisio portreadu manylion bywyd bob dydd yn y cyfnod.

Y 1940au? A ellid dweud eu bod yn hanesyddol mewn gwirionedd? Mae’n rhaid bod yr amheuaeth ynghylch hyn yn taro llawer o awduron nofelau ditectif sy’n ystyried gosod nofel nôl yn y 1940au. Wedi’r cyfan, mae gan gymaint o bobl atgofion byw o’r cyfnod. Mae eu hanesion am galedi’r dogni, y cyfyngiadau ar deithio ac ‘ymdopi a thrwsio’ yn gyfarwydd iawn. Ac ar wahân i hynny, gall gosod nofel yn y 1940au edrych fel dewis hawdd. Dogfennwyd y cyfnod yn drylwyr ac mae’n gymharol hawdd i ganfod gwybodaeth am beth yn union roedd pobl yn ei fwyta, sut beth oedd eu gwisg ac i ryw raddau, sut roeddent yn meddwl ac yn ymddwyn. Recordiwyd eu lleisiau hyd yn oed ar ffilm ac ar y radio. Ac yn ddiau, mae absenoldeb dyfeisiau electronig a’r unigedd sy’n ganlyniad i delathrebion ansoffistigedig yn ei gwneud yn haws i lunio stori dditectif. Eto, wrth ysgrifennu, gall beth a ymddengys mor gyfarwydd gyflwyno pob math o feini tramgwydd annisgwyl wrth geisio portreadu manylion bywyd bob dydd yn y cyfnod.

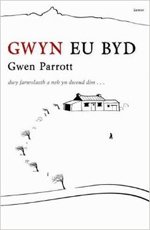

Mae cefn gwlad Sir Benfro, lleoliad fy nofel Gwyn eu Byd (Dead White yn Saesneg), yn cyflwyno nifer o heriau o’r safbwynt hwn. Mewn llawer ffordd, byddai bywyd yno yn y 1940au wedi bod yn debyg i fywyd yn yr oes Edwardaidd. Nid oedd gan lawer o gymunedau gwledig gyflenwad trydan hyd nes ddiwedd y 1950au, er bod cymunedau trefol wedi bod ar y grid ers amser. A dweud y gwir, pan fod rhywbeth mor hanfodol i fywyd modern fel cyflenwad trydan yn eisiau, gall danseilio, mewn ffordd gynnil, holl gynlluniau gofalus awdur. Mae’r angen i fod yn gyson wyliadwrus, i bwyso a mesur dewisiadau plot yn erbyn meini prawf sydd erbyn hyn yn ddieithr i ni, yn wrthdyniad. A allai’r cymeriad hwn fod wedi gwneud hynny mewn tywyllwch dudew? Pa drefniadau oedd gan bobl er mwyn berwi tegell yn gyflym neu er mwyn cadw bwyd heb rewgell? Gall fod o gymorth i ddychmygu eich bod ynghanol toriad cyflenwad parhaus, ond mewn gwirionedd, nid yw dulliau modern o ymdopi’r un peth â dulliau’r 1940au. Mae’n ofynnol i awduron ymgyfarwyddo â chanwyllbrennau a lampau paraffin, tanau glo agored a bwyleri cefn, a thortsh ddibynadwy hanfodol. Nid oedd gan lawer o gartrefi stafell ymolchi na dŵr pibell ychwaith. Byddai hyd yn oed yr ysgol leol wedi dibynnu ar danau glo agored, ac ar y disgyblion hŷn i ofalu amdanynt. Mae’r ffaith bod plant anacademaidd mewn ardaloedd gwledig wedi aros yn yr ysgol leol elfennol nes gadael yn bedair ar ddeg yn nodwedd arall o fywyd a ddiflannodd o’n hymwybod. Mewn rhai mannau ni wireddwyd bwriad Deddf Addysg 1945 i ddarparu addysg uwchradd i bawb nes y chwedegau cynnar. Ar y cyd â’r holl gyfyngiadau dogni, a oeddent mewn grym nes 1953, daw’n amlwg bod hwn yn fyd cwbl wahanol.

Yn rhyfedd iawn, roedd lleoliad Gwyn eu Byd ynghanol gaeaf erchyll 1947 o gymorth oherwydd bu’n fodd i ddwysáu’r gwahaniaeth a’r unigedd. Bryd hynny, ni fyddai hyd yn oed y posibiliadau cyfathrebu cyfyngedig a ddarparwyd gan yr ychydig dai gyda theleffon a’r blychau ffôn cyhoeddus wedi bod yn hyfyw. Bu’n rhaid i bobl droi nôl at adnoddau cyfnod cynharach fyth, fel defnyddio ceffyl a throl i glirio’r ffordd ar gyfer y lori laeth. Daeth cydweithredu, a oedd bob amser yn nodwedd o gefn gwlad Cymru, yn gwbl anorfod er mwyn goroesi.

Fodd bynnag, er bod diffyg mwynderau yn y 1940au wedi cilio i niwl hanes, mae anghydraddoldebau rhyw’n dal i ganu cloch. Hwyrach mai hanes teuluol sy’n gyfrifol am hyn, yn f’achos i. Bu’n rhaid i’m mam-gu, un o’r merched prin hynny â gradd ers 1916 roi’r gorau i’w swydd fel athrawes ar ôl priodi. Nid yw’n syndod felly bod gwneud f’arwres, Dela Arthur, yn dra amddiffynnol o’i hannibyniaeth, wedi dod yn naturiol i mi. Byddai ei statws yn y gymuned, yn rhinwedd ei haddysg a’i swydd, wedi dwyn ei gyfrifoldebau a’i gyfyngiadau ei hun yn ei sgil. O safbwynt y stori, mae gan hyn oblygiadau. Mae lleoedd lle nad all Della fforddio i neb ei gweld, fel y dafarn leol, y ‘Cwt’. Nid yw hynny’n gyfleus o gwbl, â hithau ar drywydd llofrudd. Gwylir a mesurir ei hymddygiad yn erbyn safonau sy’n ymddangos yn afresymol nawr, ond roeddent yn un o wirioneddau’r cyfnod.

Wedi dweud hynny, hawdd anghofio nad yw’n stryd un ffordd. Nid yw’r 21fed ganrif yn fwy rhyddewyllysiol na’r 1940au ym mhob peth, oherwydd er byddai Dela wedi cael ei beirniadu’n llym am yfed alcohol, byddai disgwyliad, bron, iddi ysmygu, oherwydd roedd mor gyffredin. O’r safbwynt hwn, un o’r adnoddau mwyaf defnyddiol er mwyn caffael darlun gwir o sut roedd pobl yn ymddwyn ac yn meddwl yn y cyfnod yw’r gyfres o lyfrau a gyhoeddwyd yn gymharol ddiweddar o’r dyddiaduron Mass Observation a gadwyd am flynyddoedd lawer gan oddeutu 500 o bobl. Maent yn hynod werthfawr, oherwydd gwelir ynddynt faint o ddoethineb chwedlonol anwir sydd wedi’i serio ar ein meddyliau, fel y gred mai dim ond ymysg y Natsïaid yr oedd gwrth-Semitiaeth yn rhemp. Ond mae tabŵau a phynciau llosg yn newid, ac mae ‘bod yn driw i’r cyfnod’ bron yn anorfod yn golygu bod yn rhaid i awduron wneud i gymeriadau y maen nhw’n dymuno bod darllenwyr yn uniaethu â nhw ddweud a gwneud pethau sy’n gwbl annerbyniol i rai pobl yn yr oes sydd ohoni. Mae’n rhaid cerdded cortyn tynn rhwng portreadu’r cyfnod fel yr oedd mewn gwirionedd a pheidio â cholli cydymdeimlad darllenwyr.

Yn y dyddiau hynny roedd cymdeithasu yng nghefn gwlad Cymru’n canolbwyntio ar ddau le, sef y capel neu’r dafarn. Roedd pobl yn perthyn i’r naill garfan neu’r llall, yn allanol beth bynnag, ond yn enwedig mewn cymunedau anghysbell, ni ddylid anghofio rôl a grym y capeli o ran gwellhad deallusol a diwylliannol. Er ei bod yn ffasiynol i’w dilorni fel mannau cul a gorthrymus, mewn gwirionedd y capeli oedd yn darparu cwmnïaeth gymdeithasol fawr ei hangen, addysg, digwyddiadau a theithiau, heb sôn am drafodaeth ddiwinyddol ac athroniaethol. Mae hyd yn oed Dela, o’i chefndir crefyddol trefol yn synnu at yr holl weithgarwch. Mae pwysigrwydd y capeli’n ymestyn hefyd i’r ffaith eu bod yn gadarnle i’r iaith, gan wella a chyfnerthu llythrennedd. Bryd hynny, byddai’r gymuned gyfan yng nghefn gwlad gogledd Sir Benfro wedi bod yn Gymraeg ei hiaith. Nid oedd llawer o bobl o ‘bant’, heblaw am garcharorion rhyfel wedi dechrau cyrraedd eto. O fewn eu cymuned, ar wahân i’r radio ac yn yr ysgol, anaml byddent wedi clywed Saesneg llafar er, wrth reswm, byddent yn ddwyieithog. Gan mai nofel Gymraeg yw Gwyn eu Byd/Dead White yn wreiddiol, ble mae atseinedd diwylliannol yn golygu y deallir pethau o’r fath yn reddfol, cododd y cwestiwn yn naturiol wrth ei chyfieithu faint o waith esbonio oedd yn ofynnol yn y fersiwn Saesneg. Mae’n ymddangos mai’r ateb yw ychydig iawn, nawr bod nofelau a gyfieithwyd o nifer o ieithoedd yn gyffredin, yn y gobaith byddai deallusrwydd y darllenydd yn llenwi’r bylchau.

Mae ymchwilio’n hawdd ar gyfer y 1940au. Penderfynu faint o ymchwil i’w stwffio i mewn i nofel yw’r rhan anodd. Rhaid cofio pan fod pobl yn byw mewn oes benodol nid ydynt yn ei thrafod yn ddi-ben-draw ym mhob sgwrs bob dydd. Maent yn gweithredu gan mwyaf ar ragdybiaethau a rennir heb eu hynganu. Yr her i’r awdur yw dod o hyd i ffordd o gyfleu gwybodaeth yn anuniongyrchol, bron ar ffurf llinell ffwrdd â hi yma ac acw, er mwyn rhoi blas o’r cyfnod i ddarllenwyr modern heb arafu’r stori. Mae’n rhaid i unrhyw wybodaeth a roddir fod yn rhan o’r stori, ac mae’n rhaid crybwyll materion y dydd yn yr un modd.

Ac ar ben hyn oll mae’n rhaid meddwl am blot credadwy ar gyfer nofel dditectif!