Colin Watson was one of those writers who certainly had his day in the sun, but is largely forgotten in these days of supermarket best-sellers and huge promotional budgets for writers thought to be the next big thing.

Watson was a modest man. Born in Croydon in 1920, he was educated at Whitgift School, which was founded in 1596 by the then Archbishop of Canterbury, to provide education and medical care for the poor and needy from the parishes of Croydon and Lambeth. In 1937, at the tender age of 17, he was appointed as a cub reporter on the Boston Guardian, many miles away. It was while working in the Lincolnshire market town, and in the villages around it, that he gathered the materials and inspiration which were to make up his novels, known as The Flaxborough Chronicles. Flaxborough itself is a kind of composite of Boston and other small towns in the area, such as Sleaford and Horncastle. Our picture above shows a Boston street scene, captured in 1945, with the unique tower of St Botolph’s Church – referred to locally as the Stump – in the background.

What’s in a name?

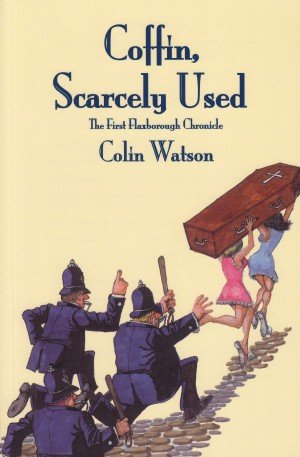

The first Flaxborough Chronicle was Coffin, Scarcely Used (1958). Aside from the crime fiction element, Watson announced himself as the latest in the long line of English authors to delight in the absurdity of peculiar names. Following on in the great tradition of Dickens and PG Wodehouse, across the 12 Flaxborough novels Watson gave us Miss Lucilla Edith Cavell Teatime, Harold Carobleat, Stanley Biggadyke and Mrs Flora Pentatuke, to name but four.

The permanent central character of Inspector Walter Purbright is beautifully named. Purbright gives us a sense of sparky intelligence gleaming out from a solid, quintessentially English, impermeable foundation. He is described as a heavy man, with corn coloured hair. He has a deceptively reverential manner when dealing with the aldermen and worthies of Flaxborough, but he is no-one’s fool. In 1977, the BBC adapted four of the novels for a TV series called Murder Most English. The role of Purbright was taken by Anton Rogers, with Christopher Timothy as Sergeant Love.

When the owner of the local newspaper is found dead, in his carpet slippers, beneath an electricity pylon, on a winter’s night, there is clearly much work for the constabulary to do. Throw into the mix a libidinous undertaker, a housekeeper who believes that ghostly forces are at work, the strangely shaped burns on the hands of the deceased, a chief constable who cannot believe that any of his golf chums could be up to no good, and a coffin containing only ballast, and we have a mystery which might be a Golden Age classic, were it not for the fact that Watson was, at heart, a satirist, and a writer who left no pomposity unpriced.

Use of language

The sheer joy of this book in particular, and the Flaxborough novels in general, is the language. Perhaps it looks back rather than forward, but there are many modern writers who would happily pay homage to the unobtrusive Lincolnshire journalist. Of Mr Chubb, the Chief Constable, Watson observes, “Not for the first time, he was visited with the suspicion that Chubb had donned the uniform of head of the Borough police force in a moment of municipal confusion when someone had overlooked the fact that he was really a candidate for the curatorship of the Fish Street Museum.”

Of the detecting skills of Sergeant Love, Purbright’s long-suffering subordinate, we learn that “The sergeant was no adept of self effacing observation. When he wished to see without being seen, he adopted an air of nonchalance so extravagant that people followed him in expectation of his throwing handfuls of pound notes in the air.”

With such an ability to turn a phrase, it is almost irrelevant how the book pans out, but Watson does not let us down. Purbright uncovers a conspiracy involving loose women, a psychotic doctor and a distinctly underhand undertaker – hence the title. Watson himself remains mostly unknown to today’s reading public, but is rightly revered by connoisseurs of crime fiction. He was politically incorrect before the phrase was even invented and, although his pen pictures of self important provincial dignitaries are sharply perceptive, they also portray a fondness for the mundane and the ordinary lives lived beneath the layers of pretension.

There were to be be eleven more Flaxborough novels, and the final episode was Whatever’s Been Going On At Mumblesby? It again features Mr Bradlaw, the shamed undertaker from the very first novel. He has served his time for his part in those earlier misdeeds, however, and has returned to Flaxborough, thus giving the series a sense of things having come full circle. In 2011, Faber republished the series digitally, but the Kindle versions are pricy and you’re better off seeking a secondhand paperback either on Amazon or elsewhere. See the links below.

Visiting assassin

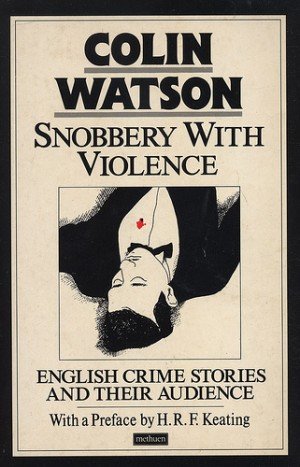

In addition to such delightful titles as Broomsticks Over Flaxborough and Six Nuns And A Shotgun – in which Flaxborough is visited by a New York hitman – Watson also wrote a scholarly account of the British crime novel in its social context. In Snobbery With Violence (1971), he sought to explore the social attitudes that are reflected in the detective story and the thriller. He also has the distinction of being the first person to sue Private Eye successfully. In issue 25, November 1962, they deemed his writing to be, “Wodehouse without the jokes.” Watson objected to this slur, and the court awarded him £750 in damages.

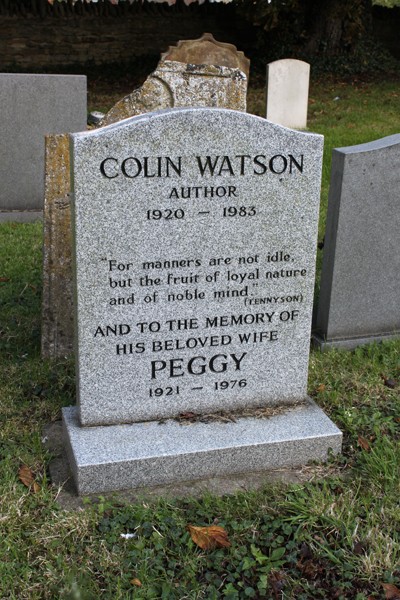

Watson took a relatively early retirement, and saw out his days in the beautiful Lincolnshire village of Folkingham, with his second wife, Anne, where he apparently spent his time writing, enjoying music and photography and took up the crafts of lapidary and silverwork. He died in 1983.

So what is his legacy? In his own time he was highly regarded by both critics and readers. He won two CWA Silver Dagger awards in 1962 and 1967, his books sold well, and Julian Symonds said the Flaxborough Chronicles have, “…all the virtues one looks for in a crime novel.”

That he is currently unfashionable is a shame, but is no reflection on a fine writer whose day will surely come again. On a more personal note, he is remembered, along with his first wife, on a memorial which stands under a beautiful chestnut tree in the churchyard of Folkingham, along with a quotation from another fine Lincolnshire writer. There is a line from the Gospels which says, “A prophet is not without honour, but in his own country, and among his own kin, and in his own house,” and it was a sad reflection on the fickleness of fame that when I visited Folkingham, the good natured locals who showed me to the headstone had no idea who Watson was, or what he had written.

If you enjoy a crime novel where the humour and the exquisite language line up alongside the plot, you might also want to take a look at this gem – The Big Bow Mystery.