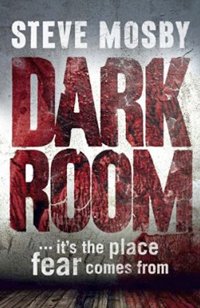

Written by Steve Mosby — In a northern UK city a serial killer is selecting victims seemingly at random, and butchering them with a hammer. As the death toll mounts, Detectives Andy Hicks and Laura Fellowes are confronted with ruined faces, ruined lives and no clues, save the tantalising anonymous letters sent to Hicks by the killer.

Written by Steve Mosby — In a northern UK city a serial killer is selecting victims seemingly at random, and butchering them with a hammer. As the death toll mounts, Detectives Andy Hicks and Laura Fellowes are confronted with ruined faces, ruined lives and no clues, save the tantalising anonymous letters sent to Hicks by the killer.

Hicks feels sure that the partner of the first victim is guilty, but when a homeless man is murdered in the same way it seems clear that the police must direct their attention elsewhere. A local prostitute, a violent club doorman and a housewife join the list of victims, and then a young mother is killed in front of her husband and child. The true magnitude of the outrages is revealed as the killer sends the police a CD containing video footage of his work. Convinced that there is a hidden link between the crimes, Hicks calls on the services of Professor Carol Joyce, an expert on codes and number sequences.

Unlike many crime novelists, Steve Mosby chooses not to have the city itself feature like character in the plot. The place is nameless, and there are no real-life street names or landmarks to anchor us to anywhere familiar. This is disconcerting at first, but then the ploy begins to work in the novel’s favour as the sense of displacement fits perfectly with the moral blankness of the killer’s world. This is a city which is unknown to us, but in another sense we have known it all our lives. It is a city which, because none of us will ever go there, becomes all the more suited to being a killing ground.

One of the most intriguing aspects of Dark Room is the back-story of Hicks and his wife, Rachel. Despite the imminent birth of their first child, their marriage has reached a sad hinterland of silences, missed opportunities and lost affection, and Mosby describes their relationship with a painful poignancy. The paths not taken, the words unsaid and the feelings un-shared are an additional shadow in the disquiet we feel about Hicks himself, as the murders bring back living ghosts from both his childhood and his younger days as a constable. There is something about Hicks that troubles both us and the people he lives and works with. Like a skilful conjuror, Mosby reveals enough to let us think we have worked it out, but when the final revelation comes with an almost blinding flash of light in the final pages, we realise that we actually knew nothing, despite the hints and clues shown us along the way.

My only quibble is that the text seems to have been Americanised. Hicks and Fellowes are referred to throughout as ‘Detective’ rather than using a British police rank. There may be a specific military position of ‘janitor’ but that job would more usually be described as ‘caretaker’ in the UK. More significantly, at least in terms of the plot, it is a major departure from the conventions of homespun crime fiction for middle-ranking police officers to be going about their routine business with a holstered sidearm.

These minor points should not deflect from the fact that this is a beautifully written and unsettling book from a skilled writer. The narrative is spun through with chilling nuances of how the past and present can collide in unexpected ways. The chains of cause and effect pull the characters this way and that, and we turn each page with a tantalising uncertainty as to how things will finally be resolved. There is the occasional nod towards police procedure, but the constabulary and its workings are largely irrelevant to the success of the book. Dark Room is not a comfortable read; it takes us to too many places where death, guilt, pity and sorrow hold sway. However, the three pages which provoked a genuinely terrifying ‘Oh God, please… no!’ moment for me had nothing to do with the murders, but struck a chord much closer to home for those of us who are husbands and parents.

Orion Books

Kindle/print

£6.99

CFL Rating: 4 Stars