While Cormac McCarthy is often hailed as the author who revived and reinvented the Western, some of his stories fit equally well within the genre we love most – crime fiction. None more so, perhaps, than No Country for Old Men, a book that sits easily alongside the great American noir novels and which has influenced crime fiction authors around the world as well as the emerging rural noir sub-genre.

The book is Cormac McCarthy’s eighth novel and was published in 2005. In 2007, the story was turned into a film by the Coen brothers, which won four Academy Awards.

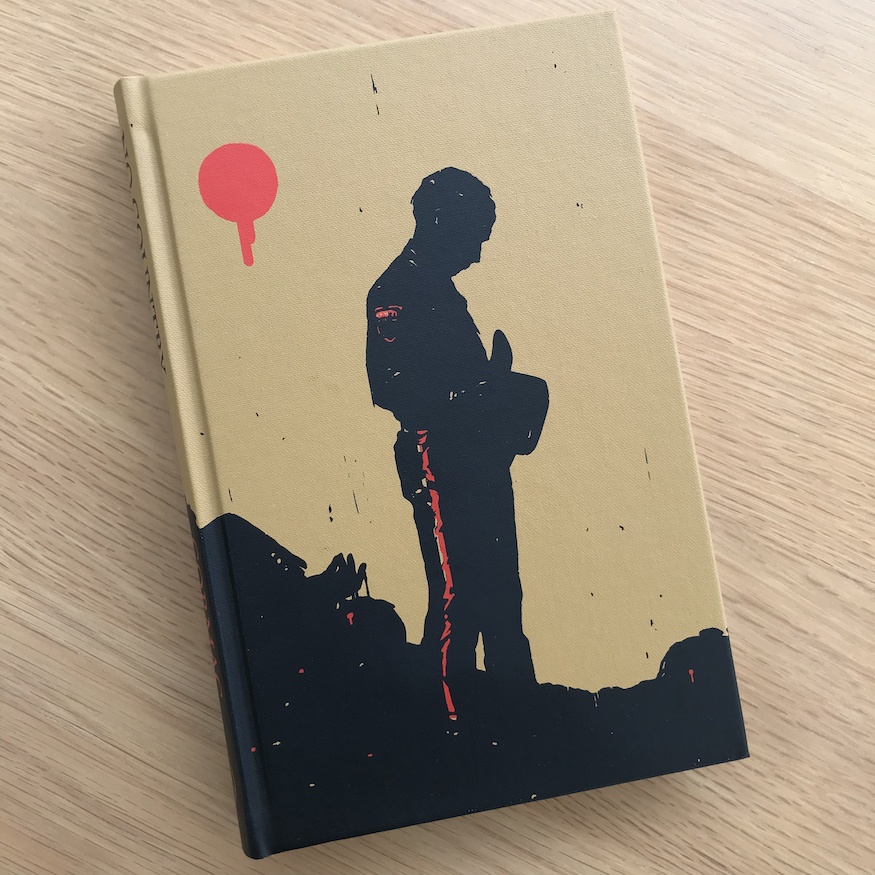

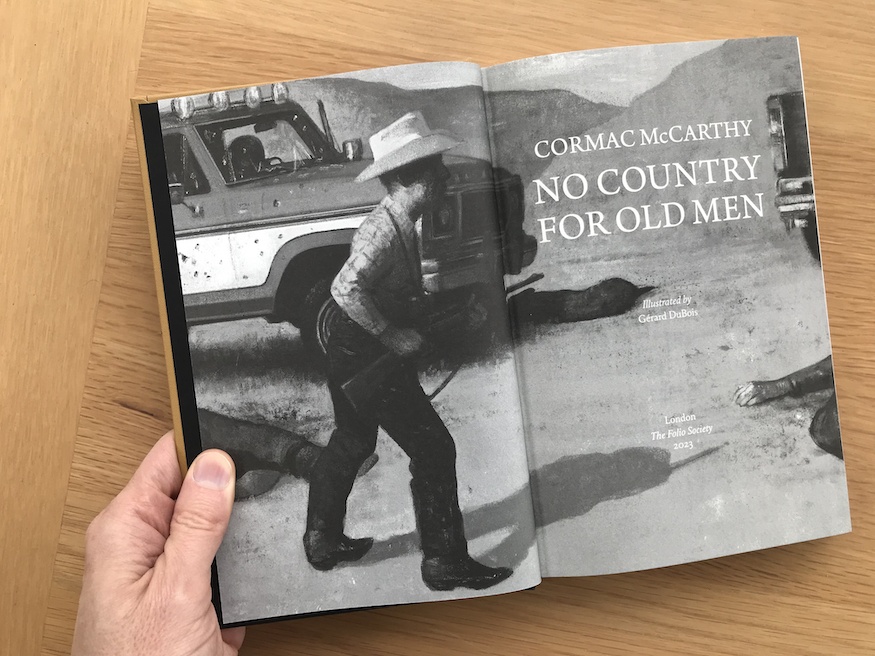

In October 2023, the Folio Society honoured the novel with a high quality, illustrated reprinting – providing us with an ideal excuse to revisit No Country for Old Men, exploring its story, themes and legacy. Delivered in a sturdy slipcase, wrapped in wax paper, and with seven illustrations by the award-winning illustrator Gérard DuBois, this edition is an object of desire for crime fiction lovers. It follows on from similar folios of The Road (2021) and Blood Meridian (2022). Sadly, Cormac McCarthy passed away in June 2023 and will not be able to enjoy this beautiful example of bookmaking, however he was able to approve and appreciate the illustrations included.

A bag of money

No Country for Old Men is about three men – a welder and Vietnam vet called Llewellyn Moss; the Sanderson, Texas sheriff, Ed Tom Bell; and a hitman called Anton Chigurh. They are completely different, yet their paths become entwined after a drug deal goes wrong near the Mexican border. The story takes place in 1980.

While out hunting antelope, Moss arrives upon the scene of a shootout. Men lie dead under the baking sun, a wounded dog slopes off into the scrubland and Moss pokes around the shot-up pickup trucks and bodies. He finds an injured Mexican asking for water, a large shipment of brown heroin and a case containing $2 million. In the tradition of noir crime fiction, Moss takes the case and goes back home to the trailer park, where he lives with his young wife, Carla Jean.

Meanwhile, Chigurh has strangled a deputy, escaped police custody, killed a man for his car using a pneumatic bolt gun, and is heading in the direction of the carnage. His connection to the gangs isn’t entirely clear but his intention is to retrieve the money and nothing is going to stop him from doing so.

Later that night, Moss returns to the scene with a jug of water but the drugs are gone and the man has been shot. He’s fired upon, wounded and chased from the area by two men but manages to escape into the river down below and sneaks back home.

Following in the wake of all the killing, Sheriff Bell arrives with his deputy and pieces together what might be going on. He recognises Moss’s truck and realises the man is in over his head – something Moss himself would never admit. Sending his wife to her mother’s, Moss goes on the run with the money, chased by Chigurh and the Mexican gangs involved. Bell makes it his mission to try and save Moss from the onslaught of violence that is coming.

You know how this ends

The themes of determinism and fatalism are close to the surface in Cormac McCarthy’s writing and this is particularly so with No Country for Old Men. Very early in the book, Chigurh stops at a gas station and reveals his strange philosophy while growing increasingly irritated by the man at the counter, who clearly would rather he left. In Chigurh’s eyes, his path has led to the gas station, the attendant is in his path, and there’s a chance the man will have to die. In the end, he asks the man to call a coin toss. Heads. He lives.

Llewellyn Moss has taken a briefcase full of cash. What could this lead to? As far as Chigurh is concerned, Moss is in his path and nothing can change that. It doesn’t matter that Moss thinks he has the wiles to escape and/or kill Chigurh. All the killing has the men in suits behind the drug trafficking worried, so they call in another hitman to deal with Chigurh. What will be the consequences of this decision?

Ed Tom Bell brings other themes to the table. How and why is America changing? Is all the drug-related violence he sees a consequence of these changes? A third generation sheriff, he ruminates about the old timers in his profession – some of whom didn’t even carry guns. Nearing retirement age, Bell is worn down by all the lives he sees wasted in the violence. There are deep morals and standards he tries to follow, and Bell is a picture of small C conservatism in the South. He’s unsure whether God is with him or not but ultimately he knows the danger Moss is in and, a decent man, he will do all he can to try and protect Moss and Carla Jean.

Although Bell seems to associate the waves of violence that are following the drugs across the border with declining values in America, there is also a scene when he and a relative look back on a common ancestor who was gunned down. It’s a reminder that the violence has always been there.

Darkness all around

No Country for Old Men takes you to some very dark places. It’s a feeling that’s hard to shake, long after you’ve folded the cover closed. When I started reading my next book – a thriller – try as the author might to engage me with his characters all I could think was, “What does it matter? They’re all going to die.” Bleak doesn’t begin to cover it.

It’s McCarthy’s prose that lights the way, however ugly, uncomfortable and soul-sapping things get. He is the most natural of storytellers. The first sign of this is his disregard for certain punctuation and he’s happy to spell words and use grammar the way his characters would. There are no quotation marks and attribution of speech isn’t always given. This is because it’s not required. It’s a form of minimalism that enriches the story. I’d argue that it brings you closer to the characters. As a reader, you connect the dots and draw them as real people in your imagination.

The author paints the borderland plains like no other, as though he owns the geography. Or, more accurately, as though his characters own it. The towns and motels that Moss and Chigurh run through are simply described; McCarthy is showing us a simpler times.

Much is said about the violence in Cormac McCarthy’s books. There’s a lot of it, along with the death and injury it causes. Buckshot tears skin, broken bones protrude, you shudder to think. Equally, there are key moments we don’t see and the event a thriller writer would build to as the story’s climax is left out of No Country for Old Men. Throughout the story, there are times when Cormac McCarthy could say more but doesn’t. Again, he trusts the reader to draw the picture themselves. The fate of the characters unfolds and we’re able to see it without knowing their every thought.

In the Folio Society edition, illustrator Gérard DuBois holds back on detail while reflecting the bleak tone of the story. The men he depicts are solid, tangible forms. Real beings. The guns, the trucks, the corpses, the boots, the motel rooms – the essentials are there, but it’s a pared back form of illustration. Again, it feels like something from a simpler time. However, in the last image in the book, when Bell is reflecting on life with an elderly relative, there is far more texture and nuance in the lighting, allowing a more contemplative atmosphere to settle.

Long live Cormac McCarthy

Joel and Ethan Coen’s superb film adaptation undoubtedly brought Cormac McCarthy to a whole new audience. It’s true to the book, and the acting hits the right notes with Tommy Lee Jones playing Sheriff Ed Tom Bell and Josh Brolin as Llewellyn Moss. Javier Bardem won the 2008 Oscar for Best Supporting Actor in the role of Anton Chigurh. The cool menace with which he calls the gas station attendant ‘friendo’ stayed with people, and even resurfaced when an episode of The Simpsons satirised the story.

The film perfectly captures what the early 1980s were like in the Southwestern United States. The trucks and the trailer parks, the rundown motels and the guns, and the long, straight, dusty roads that are still there today. Simplicity and innocence are contrasted with the hard, hot landscape, the bloodshed and the inevitability of death.

While researching this piece, I wondered for a nanosecond how much Cormac McCarthy has influenced other crime authors but knew deep down that the answer is: a lot. Names of authors whose work feels informed by his come quickly to mind. I asked two of my favourites their thoughts on Cormac McCarthy and No Country for Old Men and I’ll give you their responses, unfiltered.

First up, Elizabeth Hand, author of the Cass Neary novels as well as numerous standalones.

“McCarthy’s depiction of Chigurh sets a high bar for evil: purely malevolent and rapacious as a bull shark, with an almost robotic urge to kill. I’ve always admired how McCarthy makes clear the moral calculus in this novel. There’s no doubt who the antagonist is, no explanation or excuse given for his pathology. I vividly recall finishing the novel and feeling a systemic dread, along with a determination never to make off with millions of dollars that don’t belong to me. Cass Neary, of course, wouldn’t think twice. She also wouldn’t make the fatal error of returning to the scene of her theft.”

Also, Adrian McKinty, author of the Sean Duffy novels and The Chain:

“I’m a big fan of McCarthy and a completist, having read the lot including the dodgy plays and screenplays. For me though it’s more the early books, the Tennessee novels that were the biggest influence. I think my style and ideas were locked by the time No Country came out. I was initially resistant to the book because of the Yeats quote – in Ireland it’s quite hacky to title anything from Sailing to Byzantium which is so overplayed as a poem, but I gave McCarthy the benefit of the doubt and finally read the novel in paperback. I loved the minimalism, the off screen death, the nihilism and the milieu. Less convinced by the supervillain but that was just a quibble.”

Noir, and then some

When No Country for Old Men was originally published, some critics noted the moral aspects of the novel, which are more or less absent in McCarthy’s other works. Decisions, consequences, the sense that a character is digging a deeper hole for themselves – or, even worse, putting others in danger – what we see in this story does more than knit in with the classic noir tradition. Rather, it makes the book an exemplar in the genre.

By 2011, when we set up Crime Fiction Lover, border noir had become a phenomenon, but few crime novels have depicted the hopeless tragedy with quite the depth or humanity. Don Winslow’s excellent Border trilogy concentrated on the law enforcement, corruption and political dimensions. Newer rural noir novels are dealing with the impact of the opioid crisis, not just in the Southwest but across America, through the lens of crime fiction.

If we look closely at Bell, we see a lawman whose objective isn’t to catch the bad guys. He’s all about protecting the people in his county. Opportunists like Llewellyn Moss are caught up in the turbulence of the drugs trade but ultimately he’s powerless. There’s no escape.

The other hitman, Carson Wells, observes that Chigurh operates to principles. Ironically, it make him seem the most honest among them. But is this really the case? Perhaps he’s insane. Or perhaps his logic is twisted to perfectly suit his bloodlust. In the film, it’s telling how the Coens show us Chigurh’s face when he’s killing somebody, and not that of the victim. The mask of rationality slips.

If good, old fashioned crime fiction is to your taste, then No Country for Old Men, in its wonderfully recreated form, must be added to your collection. Below, we’ve included some photos but it’s not just how this folio looks, it’s how the cloth binding feels in your hand, and the smell of the paper and ink, that make it as visceral as the story itself. You can order a copy here for £49.95.