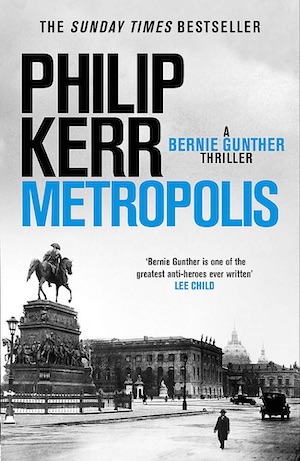

Written by Philip Kerr — The tragic passing of Philip Kerr last year means that Metropolis is the last book in his hugely popular historical crime series featuring the German detective Bernie Gunther. You can read a full rundown on the series here, and if you do, you’ll see that the author loved jumping forwards and backwards along Gunther’s timeline, through the 1940s, 50s and 60s, alighting here and there and having his war-scarred detective solve a morally testing case. With Metropolis he takes us back earlier than ever before in Gunther’s career, to 1928 during the Weimar Republic period in German history.

It’s not quite an origin story, though. Gunther has already been hardened by his experiences in the trenches of World War I – though they still haunt him – and made cynical working in a Berlin police force riven by the kind of personal ambition you’ll see in any big city department, and by strong political opinions that you probably won’t. The head of the crime investigation unit, Bernard Weiss, a liberal Jew, promotes Gunther to the role of detective and his first file has a catchy title: the Silesian Station murders.

Four prostitutes have been slain by hammer blows to the head, and then scalped. However, there is hesitancy from the start over how much the case should be investigated. Gunther, morally driven to solve crimes, is ready to go, but the wider, more right-wing view is that the girls had it coming to them. A few less prostitutes will make Berlin a cleaner place, never mind the fact that women’s wages are so low many are driven to go ‘on the sledge’, as Gunther puts it, to make ends meet. Sometimes, their husbands are behind the decision.

At one of the murder scenes, Gunther finds some flowers. He manages to track the sender down, one Herr Angerstein. Achtung! He’s part of the Middle German Ring, an organised crime syndicate running the Prussian underground. It turns out Angerstein’s daughter Eva was one of the victims and he wants revenge. Gunther is sympathetic, and against his better judgement agrees to a pact with the gangster.

The other big twist is that all of a sudden, murders featuring the hammer-and-scalp MO cease. Then another spree starts. Now, disabled beggars – all crippled by their World War I injuries – are being shot point-blank in the head with a .25 calibre handgun. Is it the same killer or not? And, what to do? Nazi agitators, eugenicists and other conservative groups see Berlin’s beggars as the embodiment of Germany’s embarrassment at Versailles in 1919. It’s a disgusting attitude but one Bernhard Weiss and Gunther have to face, and then the former has an idea. He suggests Gunther goes undercover as a beggar in a move towards ‘method’ policing.

This proves to be a formative experience for the detective who, once he has a street-eye view of Berlin, stops feeling so sorry for himself and even eases up on his chronic drinking. The make-up artist who helps him get into the role of a klutz, as the beggars are called, becomes Gunther’s love interest, but Weiss’s plan turns out to be riskier than anyone expected…

Even if you’ve never read a Bernie Gunther novel before, you’ll be drawn into the textured and over-politicised world Kerr creates around his hero. It’s a dark and fetid Berlin he inhabits. Progressive and liberal attitudes are strongly contrasted with ways of doing things that seem almost medieval. The morgue, for instance, is fully open to the public and people are encouraged to come gawp at murder victims, while capital crimes are still punished with the guillotine. Add into the mix the modern extremism of the Nazis and Communists – both of whom hate the police – alongside powerful antisemitism and we see a city bubbling with anger and resentment. Kerr reflects what today’s politics could become if democracy is further undermined by opportunist populism.

As with Babylon Berlin, you’re dropped into a city of immense innovation and creativity, where just about anything goes. Fritz Lang is planning his film M, and Gunther is asked to meet the director’s wife to pass on his insights on murder investigations. While posing as a beggar, Gunther is sketched by an artist called Otto, who is reflecting on the legacy of Prussian militarism and the brutality of war. It’s Otto Dix, the famous Dadaist, whose unnerving Metropolis triptych is used to introduce the book’s sections: Women, Decline and Sexuality.

But where Babylon Berlin highlights some of the opulence of the city alongside its dark underbelly, Kerr’s rendering is weirder and darker, lightened only by those culturally delightful vignettes with historical figures of the day and Gunther’s cold-yet-poetic quips where, curiously, he turns to his own cynicism to analyse the cynicism of others. If there’s a flaw anywhere in this book, it’s that the wrap-up packs in a couple of ‘and another thing’ passages that jar with the overall poignancy of the work.

The saddest thing of all, though, is nothing to do with how the last scenes play out. It’s the tragic feeling that this wasn’t meant to be the last Bernie Gunther novel. There’s nothing any of us can do about that but if you love detective fiction, if you love historical crime, it’s really not worth missing Metropolis. That would make about as much sense as doing a deal with a badass 1920s German gangster…

Quercus

Print/Kindle/iBook

£11.22

CFL Rating: 4 Stars