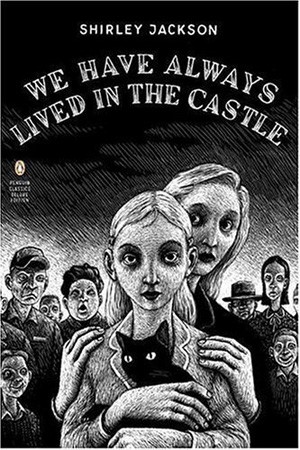

We Have Always Lived in the Castle was the last of Jackson’s six novels and came out in 1962. It is her best known work and is a good place to begin with this author. The first movie adaptation of the book is due to come out later this year, starring Taissa Farmiga and Alexandra Daddario, alongside Sebastian Stan and Crispin Glover. A release date hasn’t been scheduled as yet, so it could slip, but when the film arrives the author should reach an even larger audience.

Life on the fringes

If you haven’t read We Have Always Lived in the Castle, it is best to enter the world of Jackson’s final novel without preconceptions, as the blurb on the back cover often gives far too much away. There is mystery and murder at the heart of this story, but the reveal is gradual and relies much upon psychological observation and external stress. It tells the tale of a small family living on a crumbling and somewhat isolated estate in a small village in Vermont, and being severely ostracised by the local community. After a tragedy that occurred six years before the story opens, the three remaining family members are: Mary Katherine Blackwood, affectionately called Merricat; her older sister Constance; and their half-senile Uncle Julian, who is mostly confined to a wheelchair and requires round-the-clock care.

Constance seems to be suffering from agoraphobia, so it is Merricat who goes out into the village to visit the library and do the shopping. These trips can be quite gruelling, as she is often ignored by the grocer, insulted by her neighbours or taunted by the local children. It is clear that the Blackwood family is regarded with suspicion, fear and even hatred. Then a long-lost cousin called Charles shows up and tries to worm his way into Constance’s affections, upsetting the precarious semblance of balance and calm that the family had managed to achieve.

Merricat must rank as one of the most unreliable narrators of all time, yet she remains a sympathetic lead. She has her fears, as well as flashes of empathy and insight. Her pathetic attempts to keep her family safe through little pagan rituals are described with great understanding for her plight. She is an isolated 18-year-old who has grown up with little normal interaction with others of her age. Her strange flights of imagination are perhaps indulged a little too much by her cat Jonas and her sister Constance, but the devotion between the two sisters is very touching. By the end of the book, however, you will be unsure as to whether the sisters’ love for each other has reached unhealthy proportions.

A horror pedigree

It won’t be the first time Shirley Jackson’s work has featured on the big screen, when We Have Always Lived in the Castle finally appears. In fact, it could be said that for the past 50 years her stories have been viewed rather than read. Horror fans will be familiar with the classic 1960s film The Haunting, with Jean Harris and Claire Bloom. It was remade in 1999, with Liam Neeson, Lilli Taylor and Catherine Zeta-Jones in the main roles. You can watch the trailers below.

The Lottery has been adapted for radio, twice as a short film (1969 and 2007) and once as a feature-length TV film (1996). However, producers seem to find it difficult to do justice to the writer’s subtle brand of unnerving close observation and moral ambiguity.

You’ll find deep underlying moral dilemmas underpinning all of Shirley Jackson’s work. Her themes seem more relevant today than ever, which perhaps explains the resurgence in popularity. Has the world become too small-minded and cruel to be able to deal with otherness in a compassionate way? And if it has, is the only solution to retreat from it and seek refuge by sticking to your own kind? Should we fear change and use all our weapons, even the most perverse ones, to keep the status quo? Her refusal to answer these questions in a simplistic way mark her as an author ahead of her time. Perhaps her time is now…