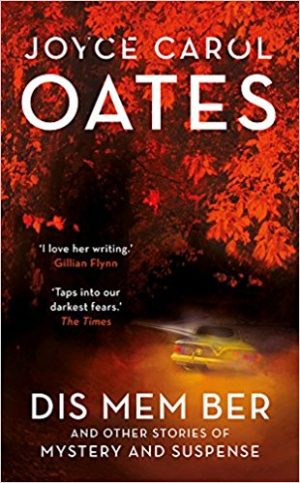

The title of the story DIS MEM BER, disarticulated and in all caps, visually reinforces the menace underlying the tale of a pre-teen girl fascinated by her older step-cousin – handsome, mysterious, and just disreputable enough to charm a young girl and enrage her father. The first-person narrator mostly misses the sinister potential in his attentions, but you will not, and you read on with growing unease.

Similarly, in the story Heartbreak, a lumpy young teen is jealous of her attractive older sister and her budding relationship with their stepfather’s handsome nephew. It opens as follows: “In the top drawer of my step-dad’s bureau the gun was kept,” perhaps written in this awkward manner as a signal that Oates will follow Chekhov’s famous advice: “If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off.”

Although these two tales turn out quite differently, they have obvious similarities and show an affinity for the voice of a young girl troubled by her sexuality and the impact on men that she has, may have, may never have, wants, and fears. Oates mimics the progress and backtracking and stuttering nature of thought with liberal use of interjected italics and parenthetical phrasing: “Even when Rowan was furious with me, and disgusted with me, still he was fond of me. This I know. It is a (secret) memory I cherish.” These devices work well much of the time, but in places feel excessive, even intrusive. Parentheses within parentheses send you down a rabbit hole.

Young girls apparently are not the only females with an affinity to second thoughts. The eerie story The Crawl Space concerns a widow haunted by, and at the same time haunting, the home she shared with her husband, now in other hands. Similarly, in Great Blue Heron, a new widow is plagued by her husband’s brother, determined to wrest the executorship of his estate – and, undoubtedly, all his assets – from her. What precisely happens in these two stories, as the women’s ghosts and fantasies take hold, is not clear. Their trace of ambiguity leaves you free to interpret. Letting readers do some of the work themselves can be a strength of the short story form.

In The Drowned Girl, a college student’s imaginings regarding the unexplained death of a fellow student become an obsession. “Like gnats such thoughts pass through my head. Sometimes in my large lecture classes the low persistent buzzing is such that I can barely hear the professor’s voice and I must stare and stare like a lip-reader.” In this, as in all of these stories, Oates deftly creates a specific, concrete setting for her characters. The believability of these environments makes you think the characters are also plausible until you’ve travelled with them pretty far into the deep weeds of their bizarre perceptions.

The final one, Welcome to Friendly Skies!, is not a thematic fit with the others, but ends the book on a decidedly humourous note. Passengers on an ill-fated flight to Amchitka, Alaska, are taken through the standard airplane safety monologue with a great many ominous additions. Frequent travellers may believe at least some of these interpolations reveal what crew members are really thinking.

Lawrence Block’s recent multi-authored short story collection, In Sunlight or in Shadow, inspired by the realist paintings of Edward Hopper, could not pass up the opportunity to include one of Oates’s lonely and deliciously skewed female protagonists.

Head of Zeus

Print/Kindle

£5.03

CFL Rating: 4 Stars