The book finishes before the jury delivers its verdict and Mahmood is asking you, as the reader, to decide on the defendant’s guilt or innocence. It’s a kind of challenge, as implied in the title, to look beyond the circumstantial evidence, and more importantly any prejudices you might have, and to see the accused as an individual rather than just another Daily Mail headline or crime statistic. An interesting concept, but does it work?

The circumstances of the case are this. A 21-year-old unnamed black man from South London is accused of murder. The victim, called Jamil, was shot and the gun linked to the killing was found in the defendant’s flat along with £30,000. There is other circumstantial evidence against the accused including witness statements of an argument between the two young men a few days prior to the shooting. Cell phone grid reports suggest they were within about 50 metres of each other at the time of Jamil’s death. The victim was thought to be a member of a local gang, and a dealer.

The defendant begins by explaining that he has chosen to represent himself because he didn’t agree with his legal advice. He maintained his innocence to his brief throughout his remand and trial but disagreed with his brief’s view that an open and frank account of his actions wasn’t in his best interests. He may maintain his innocence against the murder charge but he certainly wasn’t squeaky clean in the weeks running up to the murder and his brief thought an admission of this would prejudice the jury against him.

Afterwards comes a description of the defendant’s upbringing which involves a strict but loving mother, a kind younger sister, but an often absent father whose various addictions took priority over the family. There was domestic violence in the home until the father left the family completely. The unnamed defendant asserts that after leaving school he avoided getting sucked into gang culture and was self-employed within the auto trade. His business was doing well enough and he had a regular girlfriend, Kira, to whom he was devoted.

Everything was fine until he, Kira, his friend Curt, and his sister Blessing, were dragged into Jamil’s life against their wishes. In his afterword, Mahmood describes how he has seen many such cases and wished, through his fiction, to explore why this happens and just where social deprivation, a failing educational system and personal responsibility meet.

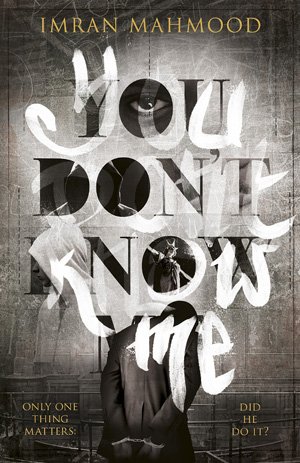

Taken on the author’s own terms the book is a success. He shows us how the odds were stacked against his defendant, and yet allows us the freedom to form our own opinions on his actions. In other words You Don’t Know Me isn’t 400 pages of didactic lecture on the ills of society.

However, judged as a piece of fictional entertainment, Mahmood hasn’t done quite as well. The main problem is with the structure. It may be novel, but the whole book is essentially a monologue, and that is a long time to stay with just one voice. This leads into the second difficulty – the defendant’s voice is neither especially compelling nor convincing. Mahmood has attempted to write in the authentic slang of a young Londoner from south of the river. It’s a heroic though uneven effort. The book begins with the defendant drawing a comparison between the actions of Viscount Palmerston defending a British subject abroad and the responsibilities of the jury hearing his case. It’s an engrossing beginning, but sadly far too eloquent when compared to the rest of the testimony, which has the uncomfortable feel of an older, middle class person trying to imitate the highly regional vernacular of a younger generation. Ali G comes to mind, but this is not satire.

If you like legal thrillers, but want a break from John Grisham or Scott Turow then you’ve got to try You Don’t Know Me just because it is so different. But be warned it can be frustrating in parts.

Penguin

Print/Kindle/iBook

£7.99

CFL Rating: 3 Stars