If you’re thinking scrubs and stethoscopes, think again, because our Sarah is studying medicine in the Victorian era, when few women were allowed to do so. In fact, the author was inspired to create Sarah after she herself was a student at Edinburgh University and saw a plaque to the memory of Sophia Jex-Blake, one of the first women to study medicine there.

It’s 1892 and Sarah is in Edinburgh, sent there from London by her parents after she brought shame upon her family. She is now in the care of her God-fearing and formidable aunt and uncle and on sufferance, Sarah is among the first women allowed into the hallowed halls of Edinburgh’s university to study medicine.

It’s an uphill struggle. Not only does polite society believe women’s brains are too small to be taxed with anything more than a little embroidery or organising the household, but the male students and most of the university faculty are also set against Sarah and her fellow females. Her relatives hope it is nothing but a passing fad and begin the search for a suitable husband, but Sarah’s past has tainted her and there are few willing candidates.

Sarah also volunteers at a clinic run on a shoestring in the slums of Edinburgh’s capital, and it is here she meets Lucy, a young whore who is pregnant and desperate to get rid of the child. The next time they meet, Lucy is a corpse, being used for anatomy practice by the students. It is an experience that shakes Sarah to the core. It appears that the young woman took her own life, overdosing on laudanum, but Sarah uncovers disturbing marks on her body and comes to the conclusion that Lucy was murdered. But who cares about the death of a prostitute and who will believe the protests of a first-year medial student, in particular a female one?

As Sarah tries to make someone, anyone, listen she comes up against brick wall after brick wall. Gossip about her past begins to spread and she loses the trust of her fellow students and is ostracised, while other unexplained occurrences mean she begins to doubt the trustworthiness of the few friendly lecturers who might have been able to help.

The lone protagonist is a well worn plot device in crime fiction, but I’ve come across few like Sarah Gilchrist. Her single-mindedness is to be admired, but she is young and impulsive and some of her decisions will have you crying out in despair. This is a tale very much of its time and Kaite Welsh does an admirable job of recreating a sense of place and period. The stark contrasts between society and the lower classes are revealed in pin-sharp focus, while the plight of women in a period when the Suffragettes were first gaining momentum may come as a shock to the liberated women of today.

The social commentary that runs through this book is fascinating without seeming too overpowering in what is essentially a gripping detective story. Sarah’s enthusiasm for her quest may ebb and flow but you will be held in thrall throughout – and the revelations, when they come, are surprising and cleverly conceived. Best of all, there’s the hint of more to come. I look forward to meeting Sarah again soon!

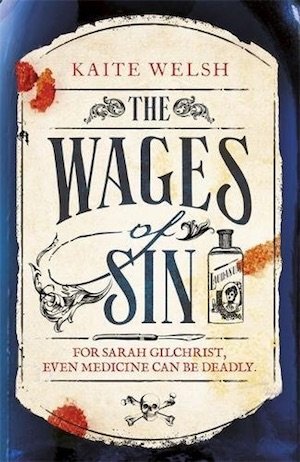

If you like the sound of it, another recent historical crime novel with a side order of medicine is Dark Asylum by ES Thomson. Another crime novel set in Victorian Edinburgh is The Strings of Murder. The Wages of Sin is out 1 June.

Tinder Press

Print/Kindle/iBook

£8.49

CFL Rating: 5 Stars