For the most part, the lives these criminals lead are unconnected. There is Raymond Butterworth, a successful printer, whose gruesome crimes are separated by decades. Then we have ‘Diamond’ Perry, the black street hoodlum who makes the mistake of taking on a Yardie drug gang. Johnny Scapes ran a high-end hairdressing business with a nice sideline in Class A drugs before a vengeful ex-girlfriend set him up for a double murder charge. Tony Masters grew up on the mean streets of South London, was abused as an institutionalised child, and has been taking it out on society ever since. And then there’s Cutler Grove – always good for a laugh, who works on his harmless Jack the lad persona, but in reality is a vicious gun-wielding thug. Brian Lincoln, another graduate of the Peckham Academy for Armed Robbers, is doing serious time after failing to relieve a discount electronics firm of its cash tray.

What binds this dismal roll call of failed villains is that they all end up in Her Majesty’s Prison, Raymar. This ficitonal jail is a phoenix in the world of incarceration. It has been rebuilt on the ashes of a previous prison which was torched during a prisoner insurrection. Raymar’s managers like to think that it is in the vanguard of prison reform, with an enlightened and sympathetic regime, informed more by hope for a better future than retribution for past misdeeds. The reality is that the prison staff are mired in a mix of professional jealousy and corruption, while the mix of inmates is an explosion just waiting to happen. When a newly appointed governor proposes taking a softly-softly approach over a drum culture spiraling out of control, one of the old school officers observes that, “These people are not like us. They are not normal. If they were, they wouldn’t be in prison.”

Ray Wilcox is uniquely qualified to write about life inside British prisons on both sides of the bars. After growing up in Peckham, his working life began as a gofer at The Daily Mirror. What followed was a 25-year career working in the Prison Service, first as uniformed officer, and then as governor. The casual violence in this book may well shock some readers, but I think we all know that brutality is endemic in prisons all over the world, and Britain is no exception. As for the men who find themselves locked up, Wilcox doesn’t seek our sympathy for them. He doesn’t sit in judgment. He doesn’t need to. Butterworth, Scrapes, Perry, Masters et al have already been judged. What he does, instead, is just to tell their story without nuances or moral spin.

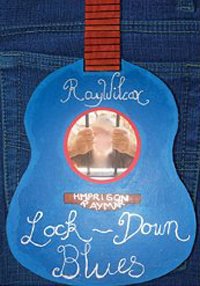

This is a bleak tale, with moments of coarse humour. It also refuses to be shoe-horned into an existing crime fiction sub-genre. You may well be half way through the book, grimacing at the misdeeds of the main characters, wondering how the narrative is going to gel, as each character’s episode seems so unconnected to the last. The threads do come together – eventually – and the outcome is worth the wait. You may also scratch your head over the opening pages, which appear to have little connection with what follows, but all is revealed at the end. This isn’t a book which grips from the first page, and is something of a slow burner, but the wasted lives of these men are like vehicles being driven towards each other on different roads, but fated to collide disastrously at some dark crossroads. You may look at the cover and expect a musical connection, but there is none, except the underlying truth in the quote from guitarist Albert Collins: “We sing the blues because our hearts have been hurt, our souls have been disturbed.“

Austin Macauley

Print/Kindle

£3.03

CFL Rating: 4 Stars