Craig Robertson explains why writing a crime novel set in the Faroe Islands is so darned challenging…

Craig Robertson explains why writing a crime novel set in the Faroe Islands is so darned challenging…

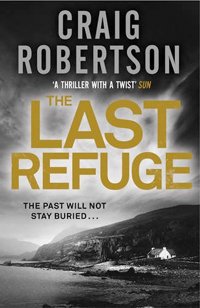

When we heard that Craig Robertson’s upcoming book The Last Refuge would be set in the Faroe Islands, at first we thought it was a brilliant idea. Robertson is a Scottish author of some repute, and the Faroes form a remote rocky outpost up in the North Sea somewhere peopled by descendants of the Vikings. Multiplying Tartan noir by Nordic noir seems like a brilliant formula on paper.

But if you look a little more closely, it can’t be easy setting a crime story in a place that hasn’t seen a murder in over 25 years. In fact, when you add everything up, it seems there are plenty of good reasons not to set a crime novel in the Faroes. We asked Craig Robertson what he thought and even though The Last Refuge is all about the Faroe Islands, he came up with five great reasons you SHOULDN’T set a novel there. Here’s what he wrote…

1 – There’s barely any real crime in the Faroes

1 – There’s barely any real crime in the Faroes

Surveys have shown that the Faroe Islands have the lowest crime rate in the world. There has only been one murder on the islands in the past 26 years. Not exactly rich pickings for a crime novel you might think.

And yet that’s partly what makes it irresistible. To take something so pure and mess with it. Who can resist leaving bloody footprints on that perfect patch of untrodden snow? Oh, just me then.

Setting a crime novel in Los Angeles or Johannesburg, or Glasgow come to that, where crime is plentiful, is like shooting fish in a barrel. The fun is setting it where there are considerably more barrels of fish than crimes.

2 – The language is baffling

2 – The language is baffling

Even to the neighbouring Danes – neighbouring being 700 miles away across the North Sea – Faroese is pretty impenetrable. It is famously non-phonetic and subsequently very difficult to pronounce. When the audio version of the book was being recorded last month, I had to set up a comical chain of contacts to allow the narrator to get the help he needed to pronounce the likes of Undir Bryggjubakka or grindaknivur.

The narrator is an Irishman, formerly from Cork and now living in New York and I put him in touch with a woman in the Faroes who I knew via a woman in Copenhagen who I knew thanks to a woman in the US whose family came from Cork. It all made perfect sense at the time.

However the Faroese language is as fascinating as it is confusing. There were words that I recognised as meaning the same as words we use in Scots – we both use kirk for church, for example. And I learned that a whole string of ‘domestic’ words, like those for cat or dog or for cooking, derive from Celtic, while ‘wild’ words such as those connected with hunting, come from the Nordic – just as the female and male inhabitants trace their DNA to the same Celtic and Nordic roots respectively.

3 – It’s even wetter than Scotland. And that’s saying something…

3 – It’s even wetter than Scotland. And that’s saying something…

It rains 300 days a year in the Faroe Islands. That soggy statistic is slightly misleading in that it need only rain for a minute somewhere on one of the eighteen islands to count as a rain day but it’s still a fair reflection on what you might expect.

Not that it rained all the time during the eight days I was in the Faroes researching this book. It also snowed twice.

It occurred to me as I stood on the rain-lashed port in Torshavn that I could have set this book somewhere warm and dry. That I could have been doing research in Las Vegas or the Maldives. I thought this about 20 times every day.

However, there is a compelling reason to love the Faroese weather, however harsh and miserable it can be. The weather is responsible for having constructed some of the most dramatically stunning scenery on earth. The wind, rain and sea have fashioned incredible sea stacks, countless waterfalls, jaw-dropping fjords and mesmerising hillsides. If you are planning to kill someone then where better than somewhere that is as beautiful as it is bleak?

4 – I love whales

Who doesn’t love whales? Well, the Japanese obviously but apart from them? And yet the Faroe Islands maintain a highly controversial tradition of hunting pilot whales and killing them on the islands’ beaches. It’s a centuries-old custom borne out of necessity but continuing in a world of easy travel and deliveries.

People, quite understandably, hold very strong views on the issue and there was a social media storm earlier this year when images labelled Danish Dolphin Slaughter went viral. There was a number of factual errors in the piece – it wasn’t Danish, they weren’t dolphins – but the basic sentiments of it are hard to ignore.

So how do I get past the moral dilemma of setting a book there? By trying to understand it.

The hunting of pilot whales until they are beached and slaughtered is undeniably brutal and makes a sickening if spectacular sight. The sea turns blood red and the carcasses are lined up to be divided up among the local populace.

To resist that, as a crime writer, would be beyond me. To understand it, without condoning it, and to lay out the conflicting arguments, is something I can do.

5 – Who’s even heard of the Faroes?

5 – Who’s even heard of the Faroes?

This is a tricky one. When I announced I was going on a research trip to the Faroe Islands, responses fell into roughly three categories. Those that thought I was going to the South Atlantic (Faroes and Falklands seem to confuse people), those that thought I was going to Egypt and those who actually knew where the islands were. I hope by the time I’m finished, the latter category will have grown a bit.

There is much about the Faroes that will recall some of the more desolate settings found in Nordic noir. Wind-battered and drenched, stark and remote, the landscape breeds stoic, determined people. It is a truly remarkable part of the world where man and land and sea are in constant conflict, where the ocean seems determined to wash it away one grain of sand at a time.

Not, of course, that the idea is to attempt to replicate Scandi crime novels. I couldn’t and wouldn’t do that. This is very much an outsider’s view of the Faroe Islands, a stranger’s look at a strange land. Like my protagonist, John Callum, I learned to love the Faroes, rain and all. I’ll let him say it for me…

“My initial downbeat impressions of drizzly, uneventful Torshavn had been lost on the wind. I now saw a different town, full of colour, vibrancy and charm. I saw calm, friendly, undemonstrative people who would go out of their way to help you.

“I had even grown to love the rain and shrug at the wind as they did. The weather wasn’t foe, it was friend, something that you could always rely on; only the form of its appearance was in doubt.”

Read our full review of The Last Refuge here.

Main photo credit: Ken Bower via National Geographic.

Craig, sounds perfect to me. -Reine

Sounds like an amazing read! Hoping The Last Refuge does increase knowledge about and interest in this fascinating location!

Such an interesting article on location as the backdrop for a novel. I guess there are very few people who are really familiar with the Faroe Islands, so this is a great way to connect and understand a new culture and terrain.

Well they kill dolphins.. wide-sided Dolphins as example.. and endangered Hyperoodon ampullatus.. just to be added to your informations.